A History of Toad’s Gender… One Way or Another

I collect obscure Mario characters. I rarely get to do all that much with them, aside from keep a running list of forgotten weirdos unlikely to ever be playable in a Mario Kart game, but there’s one whose accidental existence makes for a handy lead-in to the story of how and why some people mistook Toad for a female character back in the day.

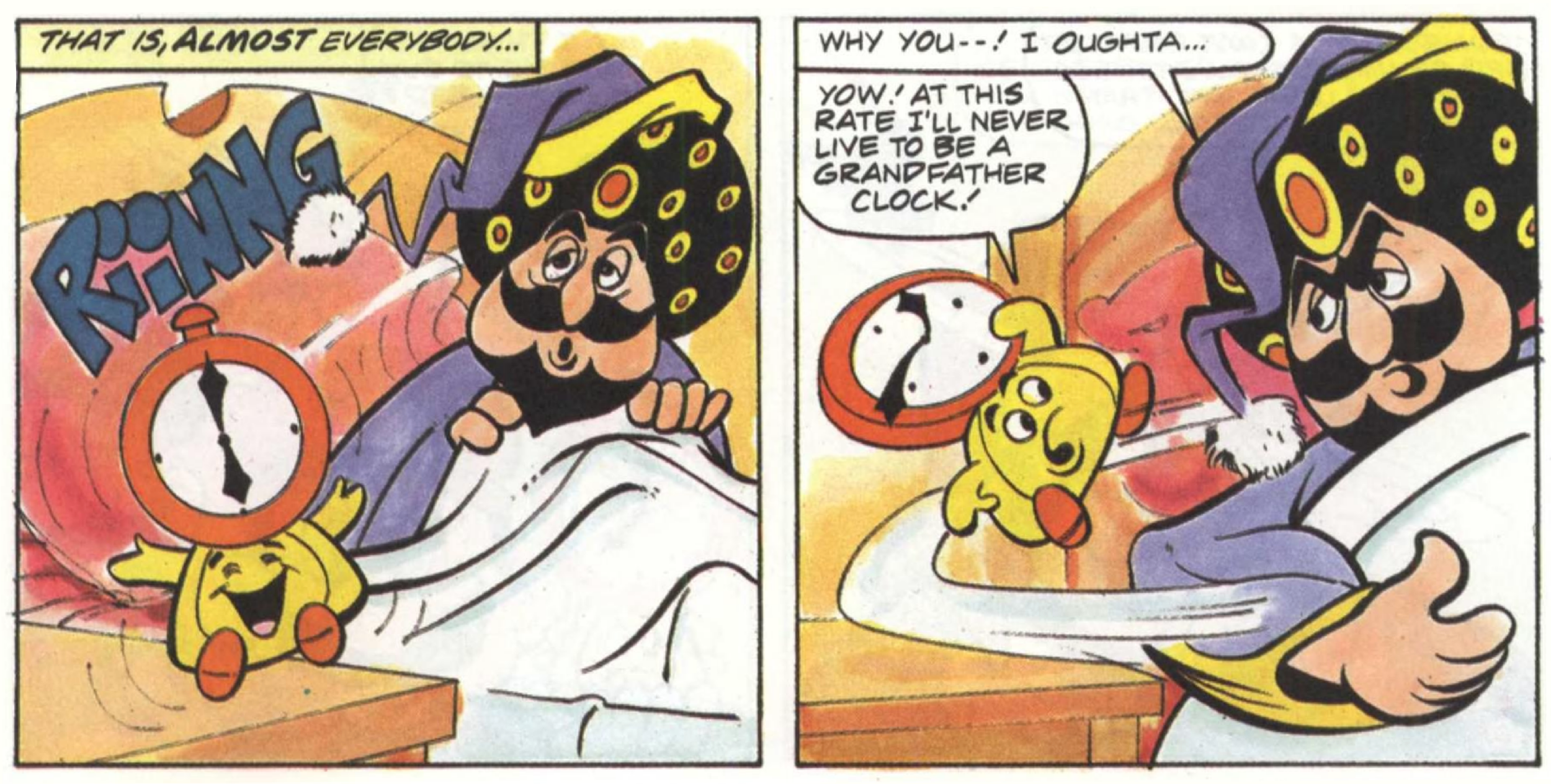

The character I speak of is Stop Watch. And yes, the appropriate response can only be, “I”m sorry — who?”

Perhaps you’ve not heard of Stop Watch. However, for a blip in the history of this franchise, he was a character who associated with Mario and his friends. For example, there’s a Valiant Comics story in which the princess’s father, King Toadstool, is awakened by this anthropomorphic time piece.

Because King Toadstool is a character that does not exist in the games — he’s mentioned in the English version of the instruction manual to Super Mario Bros. but not the Japanese one — a reader might guess that Stop Watch was also invented for the comics. This is not exactly the case; Stop Watch originates in Super Mario Bros. 2, but by accident. As this Supper Mario Broth post explains, the character likely came about because someone misinterpreted what is seen on screen in the game.

The Super Mario Bros. 2 instruction manual showcases all the items the player can collect, but the stop watch item is unique in the game in that it doesn’t appear on screen for very long. Once you pull it out of the ground, it vanishes into thin air, causing all enemies to freeze in place. So when it came time for the production team to photograph all the items in the game, they couldn’t get the stop watch isolated on screen like they could all the rest of the pluckable, chuckable items. The best they could do was to snap a photo of Mario, squatting as he pulled it from the ground and hoisting it above his head the moment before it disappears.

The combination of this gameplay mechanic plus the difficulty of photographing onscreen pixels apparently made someone misinterpret the information being conveyed. They saw Mario’s face — two dot eyes and a mustache defining his nose — as a smiley face, and Mario’s bent arms and legs as tiny appendages coming off the torso. Clearly, whoever read it in this way had not played the game, as no tiny-bodied clock abomination exists in SMB2, but just looking at the page of the instruction manual, I get how someone made this mistake. Pixels can only say so much, and especially when that information is being transferred through a CRT monitor, it’s easy to misread.

From the SMB2 instruction manual, via.

Official, Nintendo-issued SMB2 art disseminated to licensees for use in merchandise, via the Video Game History Foundation.

Which brings us to Toad and the idea that Peach’s loyal retainer was supposed to have been female — a handmaiden rather a member of the royal guard. He wasn’t, but I think this interpretation existed back in the day for the same reason that someone mistook the stop watch item for a talking, walking, existing character.

However, given the way Toad would evolve over the years and the way gendered versions of him would bud off into their own entities in true mushroom style, it’s actually very appropriate that this perception would go back to the earliest days of the Super Mario series. In fact, by most accounts, Toad was not conceived as being male or female, leaving players to interpret the character in ways that reflect their own interpretations of gender. As we’ve changed, so has Toad, sometimes in surprising ways.

The Lady or the Mushroom?

Technically speaking, Toad doesn’t exist as an individual entity until the western Super Mario Bros. 2, but even from that point on, it’s often not clear if any given character named Toad, with the blue vest and the red-spotted mushroom cap, is *the* Toad or *a* Toad. It may not matter, and for the most part, any of the discussion of Toad’s gender applies to one and all of them, save for some exceptions I’ll mention later on. In Super Mario Bros., characters who more or less look like what we know today as Toad await Mario in the dungeons at the end of the first seven worlds, whereupon they give him the iconic message, “Thank you, Mario! But our princess is in another castle!”

Right from the get-go, however, the nature of these characters is ambiguous, in the English localization and in the original Japanese both. The instruction manuals for either version of the game differentiate between the mushroom-headed characters you see on screen and a larger species of mushroom folks you don’t actually see in the games. The English version of the SMB instruction manual identifies these non-princess dungeon captives as Mushroom Retainers. The same booklet also identifies a second group, however: the Mushroom People, whom Bowser turns into “mere stones, bricks and even field horsehair plants.” We’re left to wonder if maybe they’re all mushroom-headed Toad lookalikes, with the Mushroom Retainers being ones with special castle jobs, but we don’t know. Later games drop this terminology, referring to all the mushroom heads as Toads. And whatever the case, when a specific, named representative of one or both of these groups shows up in SMB2 as a playable character, he’s identified in that manual as “Toad (Mushroom Retainer).”

And BTW, I’m going to be referring to Toad — that is, *the* Toad — using male pronouns in this piece, both because that’s what Nintendo’s English-localized materials generally do but also because I’ll be using they to refer to all Toads as a species. If there wasn’t this one-versus-all distinction to the character, however, I’d probably use they, just because the people making these games have stated fairly clearly that Toad wasn’t conceived of as being male or female.

Via.

Meanwhile, the Japanese SMB manual identifies the end-of-level hostages as キノピオ or Kinopio, presumably a portmanteau of kinoko, “mushroom,” and the Japanese rendering of Pinocchio, ピノキオ or Pinokio. (I explain why Pinocchio might be getting a shoutout in the miscellaneous notes section at the end of the post.) Indeed, Kinopio is the name used for playable Toads in the Japanese versions of later games, but it’s often unclear how unique or specific any Toad is supposed to be in the way that Yoshi is Mario’s dino buddy but also a whole race of basically identical creatures that are also named Yoshi. However, early on the franchise, there’s also these terms キノコ一族 (Kinoko-ichizoku) and キノコ族 (Kinoko-zoku), both meaning “Mushroom People” and presumably referring to the same mystery group referred to in the English SMB manual.

Note how none of these descriptions says anything about gender. In 2014, Shigeru Miyamoto did an interview with YouTube personality iJustine in which he explained that gender wasn’t considered when the character was created for Super Mario Bros. and only became a factor in the series when Toadette was introduced.

Actually, when we made the original Toad, we didn’t really have in mind whether Toad was a boy or a girl. We just made the character, and then ever since, Toadette has started appearing in games. I think people have come to take the impression that Toad was a boy because Toadette was a girl, but obviously, there’s lots of different Toads that have been in a lot of different games.

Now, I don’t want to be the guy telling the creator of the Super Mario games that he’s not correct about characters he is responsible for bringing into existence, but here I go: Yes, this is a “word of God” moment where Miyamoto is definitively saying that Toad was not conceived of as male or female and that concepts of gender came along after the fact, but I also think he’s wrong in saying that only happened with the arrival of Toadette. The history of people gendering Toad one way or another goes back to the earliest days of the franchise.

For instance, The Official Nintendo Player’s Guide, a 1987 publication from Nintendo offering general tips for the most popular NES titles of the time, incorrectly identifies the Mushroom Retainers as both the princess’s maid and as a single character, as opposed to seven different characters appearing at the end of the first seven worlds.

There’s a similar choice made in the anime adaptation, Super Mario Bros: The Great Mission to Rescue Princess Peach. Released July 20, 1986, just a few weeks after Japan got the SMB sequel we in the west call The Lost Levels, the hourlong film offers a snapshot of the Mario canon before the release of Super Mario Bros. 3, when there just weren’t many characters to choose from. As a result, the script invents characters such as effeminate dreamboat Prince Haru, and when it comes to interpreting the captured Mushroom Retainers, it envisions them as distinctly feminine handmaidens. At one point in the film, Mario and Luigi end up in a field of mushrooms, whereupon Luigi picks up a coin. It starts glowing and transforms into a character who identifies herself as Peach’s maid. She’s roughly as tall as Mario and Luigi, which is to say not short like Toad is typically shown to be.

Later, Mario and Luigi fight off Lakitu and a second handmaiden shows up, apparently having been transformed into a cloud previously. She’s colored similarky to the previous speaking handmaiden, but as near as I can tell, they’re voiced by different actresses — the first by Yuriko Yamamoto and the second by Hiroko Emori — so it may be they’re supposed to be two separate characters.

Making these characters female might seem like an unusual aesthetic decision now, but at the time, I’m pretty sure that the film’s character designers were merely making sense of what is shown in pixels in the first Mario game. Don’t forget, after all, how those end-of-level Mushroom Retainers look. Looking at the sprites today, it’s easy to see how Nintendo was doing its best to replicate in pixels how these mushroom folks were depicted on the original SMB box art. They look pretty close to how Toad looks today — and certainly closer than how Peach and Bowser look in the art.

Notably the same color scheme as Peach’s SMB sprite, but that’s probably because they’re matching the color scheme of the dungeon levels.

Try not to overthink the implications of these captive Toads having belly buttons. Unless I’m mistaken, they never would in official Nintendo art again.

I guess the SMB sprites are a decent approximation of this look, given the limited number of colors available. I mean, how would *you* arrange pixels to represent a vest but still differentiate the mushroom person’s head from the torso? I don’t know, but Nintendo’s best effort to do this results in something that looks just as much like a female character wearing a blouse or even a bikini top than it does a less distinctly feminine character wearing a vest.

Turning the Mushroom Retainers into female characters might seem like a daring choice on the part of the people who made this movi, but it also just might have been them making sense of what they saw on screen. There’s a 2013 post on Legends of Localization about this very phenomenon, in which Clyde Mandelin cautions fans not to discount the anime’s influence, saying, “I guess you can take it however you like, but at the very least it seems that a number of Japanese fans fondly remember Kinopios as being girls and wonder at what point they became guys.”

As a result of what I discussed in this section, you’ll still occasionally encounter the idea that this character, despite how he’s treated today, was supposed to have been female originally. That’s not true, but I think Nintendo sending Toad out in the world as a character who was neither male nor female left a lot of room for interpretation. And back in the day, when there was less societal discussion of the subtleties of gender, people interpreted him as one or the other.

To a degree, these conversations have never really gone away with Toad, and in fact we’d have some very similar ones in a few years, when we first heard him speak.

The Highest Voice in Kart-Racing

In the west, any speculation about Toad’s gender largely flew under the radar, and I suspect one major reason for this is that we got an explicitly male version of Toad in the DiC-produced cartoons The Super Mario Bros. Super Show! and The Adventures of Super Mario Bros. 3. Not only was he male, this Toad was also explicitly one character and not a whole race, so the cartoons sidestepped all of the identity issues surrounding this character in Japan. Most western gamers wouldn’t realize these issues existed until years later.

Sure, these cartoons were not canon to the games, but again, these extraneous versions of the Mario characters shaped perception of the franchise nonetheless. In the cartoons, Toad had a husky, gruff voice that actually set up viewers for a big surprise when they would eventually play Mario Kart 64. This clip from the very first Super Show cartoon, shows that his voice, by John Stocker, was similar in tone and accent to the ones Mario and Luigi had. He might as well have been from Brooklyn himself.

Oddly enough, Toad’s in-game voice has come to sound a lot more like the Super Mario Super Show version, but that wasn’t always the case. Toad first spoke in the Super NES version of Wario’s Woods, which came out in 1994. That wasn’t a game that a lot of people played, and while I discuss this very off-brand version of Toad in the miscellaneous notes section, most gamers’ first time hearing Toad’s voice came in 1997 with Mario Kart 64.

Especially compared to how Toad sounded in the DiC cartoons, this version came off as… more chipper, let’s say.

For the English localization of the game, Toad’s voice was supplied by Isaac Marshall, a game tester who worked for Nintendo of America. (He also apparently voiced T.J. Combo and Eyedol in Killer Instinct, so the dude has range.) In the Japanese version of Mario Kart 64, Toad was voiced by Tomoko Maruno, who would also voice the character in all versions of the first three Mario Party games as well Mario Kart: Super Circuit. Your mileage may vary, but I think Maruno’s version sounds more feminine and child-like of the two.

Toad’s effeminate Mario Kart 64 voice is what prompted Electronic Gaming Monthly to run a four-page feature in its December 1997 issue specifically on confusion around Toad’s gender. The piece was headlined in a very of-the-era Jerry Seinfeld-style: “What’s the Deal With Toad?” Speaking as a gay person who remembers what the vibe was like in the late 90s, this was not the easiest thing to read then, because it implies that Toad’s voice somehow betrayed what longtime gamers had come to expect from the character. By extension, if you act in a way that doesn’t meet everyone’s gender expectations, people are going to speculate about what’s going on with you. Does the piece mention both The Crying Game, It’s Pat and Dennis Rodman? It sure fucking does, because 1997.

I’ve combined the scans from archive.org below so you can read the piece in its entirety, should you want a reminder of the golden age of gaming magazines.

Obviously, I am not saying that it’s pointless to write about the gender of a video game character. I wrote this, so I think there’s a lot of interesting discussion to be had about how fictional characters express the gender ideals of the society in which they’re created. This EGM piece, however, seems more interested in having a goof at gender weirdos. So while I don’t love it, I’ve got to say that it could have been so much worse, honestly. The writer notes at least points out that it would be rude to ask a person “if he was a dude” and even clarifies why Toad is being referred to with male pronouns. In 1997! Maybe best of all, it’s a mainstream publication pointing out that Toad isn’t really masculine or feminine, long before Miyamoto would acknowledge on record that that this is the case. Given the age range of people who were reading EGM back in the day, I’d imagine some of them might have even learned the word androgynous from this piece.

All that said, it is very much a product of its time in how it fails to imagine any version of gender existing outside a strict male-female binary. The subhed says it all: “It’s the question that had to be asked, and only EGM has the guts to find the answer. Is Nintendo’s mushroom-headed hero a dude or a chick?” It’s not allowing room for anything else — or anything that might accurately describe this rather nonbinary-seeming character.

As baffling as that piece might seem in 2023, it does represent a more polished version of what was happening in online gaming communities back in the late 1990s: American gamers were beginning to understand that certain characters and concepts existed differently in other countries than they did in the U.S. Sometimes these conversations zeroed in on representations of gender and sexuality in video games. More often than not, the language used would demonstrate how people lacked the capacity to discuss these things maturely, which is to say that message board discourse back in the day more or less amounted to “LOL is Toad gay LOL???”

I clearly remember jokes about the fact that Toad was given the rainbow-patterned racquet in the Nintendo 64 installment of Mario Tennis. It wasn’t great. It was, however, another discussion about gender. Rather than “Wasn’t he a female character originally?” it was “If he’s a male character, why isn’t he acting like I think he should?” These conversations would continue into the Gamecube years, thanks to Nintendo giving players more Toads — and more diversified Toads.

The Nonbinary Toad and the True Princess Toadstool

Before Toadette debuted, Nintendo made another decision that either clarified or complicated the way gender works among Mushroom Kingdom denizens. In 2002, Nintendo released Super Mario Sunshine, which gave the series Toadsworth, a doddering old man mushroom who served as Princess Peach’s steward. (His Japanese name, キノじい or Kinojī, would seem to be a portmanteau of Toad’s Japanese name and おじいさん or ojī-san, “old man.”) Sporting a white mustache, Toadsworth reads as old but also explicitly male in a way Toad never did. This character was briefly recurring in the Mario games, even being playable in two baseball titles before Nintendo seemingly lost interest in him. (He is, however, the most powerful opponent in a Mario mahjong game, and that seems about right for the oldest guy in the Mushroom Kingdom.)

A character who’s had a very different trajectory is, of course, Toadette. In 2003, Nintendo released Mario Kart: Double Dash!!, a twist on the usual racing spinoff formula that put two racers in each vehicle. All of them needed a default partner, and rather than plumb the series archives for an existing character who could be paired with Toad — there was one, BTW, and I explain why she got screwed in the miscellaneous notes section — the design team created Toadette, who scans as female in the way that Toadsworth does male.

Female Toads had already appeared in RPG spinoffs, but this new character appearing in a closer-to-mainstream game seemed to represent Nintendo saying that she was a sort of complement to regular ol’ Toad. As years went by, more games featured Toad and Toadette as a pair, and I think as a result some players came to see them as a binary: Toadette is the girl version of Toad, so that must mean Toad is the boy. That’s not necessarily the case, especially if you stop and consider for a moment that there’s more nuance to gender, in the Mushroom Kingdom and otherwise. In fact, Toad and Toadette’s biggest game to date, Captain Toad: Treasure Tracker, brought about another interview suggesting that Toad’s default state is neither male nor female.

In 2014, Gamespot interviewed Koichi Hayashida, director of Captain Toad. In the piece, he says that he’d not given much thought to Toad’s gender — and what’s more, he hadn’t given much to the gender of Toadette, who is the secondary protagonist in the game. A paraphrase of the interview states Hayashida thinks that Toads “are a genderless race that take on gendered characteristics.” He’s then quoted as saying that “this is maybe a little bit of a strange story, but we never really went out of our way to decide on the sex of these characters, even though they have somewhat gendered appearances.”

Some people have interpreted this interview as meaning that Toads actively choose their gender, but the text doesn’t say that explicitly. Perhaps something gets lost in the paraphrasing, but “take on gendered characteristics” could be interpreted a few different ways, with that process being active or passive. (Does a Toad choose what gendered characteristics to take on? Can they choose none?) And while that wording comes from the person who conducted the interview and not Hayashida himself, it’s nonetheless a nod from someone at Nintendo that Toad’s gender might be different than what many gamers presumed it to be.

However you view Toad, it’s pretty clear in both Japanese and English that Toadette is the female version of him. Her Japanese name, キノピコ or Kinopiko, is just Kinopio combined with the diminutive feminine suffix -ko. The English suffix -ette can also convey smallness and femininity — a cigarette is a small cigar but not necessarily a female one, and a bachelorette is a female bachelor, but she’s not necessarily small — so it’s pretty easy to understand how the localizers came to decide on her English name.

Their choice also makes for a handy comparison to another pop culture character: Smurfette, the first female Smurf and the character who shifted perception of gender in that fictional world in a way that’s not dissimilar to what Toadette did to the Toads. One major difference is that for the Smurfs, the one gender they all shared was male — their leader, after all, has a beard and goes by “Papa” — whereas Toad was just never quite so clearly masculine in the games. For what it’s worth, Toadette doesn’t function like Smurfette in that Smurfette is the embodiment of all things feminine in the Smurfs franchise, at least until it evens out the gender ratio with additional female characters. Toadette is never tasked with that, because she joined the Mario series when multiple female characters already existed. In fact, before too long, she was allowed active, playable roles rarely afforded to other female characters.

In 2009, New Super Mario Bros. Wii marked the second installment in a new subfranchise characterized by a more two-dimensional experience — a return to classic Mario-style platforming, in a sense. A major difference in these games, however, was the option to have four players on screen at once, controlling Mario, Luigi and then Blue Toad and Yellow Toad. Though technically nameless and not even necessarily singular characters in the way Toadette and Toadsworth may be, those new Toads appeared again in the 2012 sequel, New Super Mario Bros. U.

But when that Wii U game was remade for the Switch in 2019, as New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe, Nintendo added Toadette to the mix, meaning that she was now playable in a mainline Mario game when many older characters like Waluigi and Daisy have never been. That might seem weird, especially considering Toadette’s humble origins as a lookalike racing buddy for Toad, but it makes more sense when you consider Toad’s earliest days, when he was confused as a right-hand maid to Princess Peach.

Excluding Super Mario Bros. 2, most mainline Mario games didn’t give players the option to pick a female character. Most games don’t give an option at all, really, and when they do, it’s Luigi. (One notable standout is the 2004 Nintendo DS remake of Super Mario 64, in which Yoshi and Wario join Mario and Luigi as playable characters.) Twenty-five years after SMB2, in 2013, Super Mario 3D World did offer female options, and this undid a lot of hemming and hawing on Nintendo’s part about why Peach wasn’t given an active role in previous games. In 2009, Shigeru Miyamoto blamed Peach’s skirt for why she wasn’t playable in New Super Mario Bros. Wii. And in 2012, the director of New Super Mario Bros. U blamed the fact that her proportions don’t match Mario’s in the way that Toad’s apparently do. Moving forward from SM3DW, Nintendo had to account for the lack of Princess Peach in light of the fact that the previously stated explanations didn’t hold up anymore.

This was complicated by New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe, which hit the Switch in 2019 but was a remake of a game released in 2012, before Super Mario 3D World. It already featured a plot centered around rescuing Peach from Bowser, and it wouldn’t exactly make sense for Peach to rescue herself. (However, hey Nintendo — please make a game where Peach has to escape from Bowser’s castle.) As a result of all these factors, Nintendo devised an unusual workaround to both the lack of female representation and the lack of playable Peach in particular. They added Toadette to the roster of heroes and then also tossed in a new power-up, the Super Crown. When tagged by Toadette specifically, the Super Crown allows her to transform into an inexplicable hybrid of Toadette and Peach called Peachette (or in Japan, キノピーチ or Kinopīchi, which is a portmanteau of Toad and Peach’s Japanese names). She looks like Peach, but more mushroom-y, and gray eyes that tell you that despite some appearances otherwise, she is not Peach, just someone who looks a lot like Peach.

Peachette’s voice acting actually features a small nod to the fact that Peachette is not Peach. Occasionally, she’ll erupt with a scratchier, more Toad-like shout, only to clear her throat and then resume her performance of something more like Peach.

While there are a few unique qualities to Peachette that more or less render her an “easy mode” character who can help even the most inexperienced player beat any level, the one most interesting for this conversation is the fact that she can use Peach’s unique floating jump that debuted in SMB2. With that, voila — Peach can’t save herself from Bowser, but a reasonable facsimile thereof can. And while Peachette’s dress is technically different than Peach’s — it, like her hair, may actually be a mushroom — it didn’t seem to be all that problematic to introduce skirt physics to a Mario platforming game.

All that said, Peachette’s existence raises a lot of questions about Mushroom Kingdom society that I don’t really expect Nintendo to answer in a meaningful way. Among them: Is Peach just a powered-up female Toad? Does that explain why a seemingly non-mushroom person is the reigning Mushroom Kingdom monarch? Is Toadette next in line for the throne? Could a powered-up Toadette stage a coup and seize it? Would we even know if she did? To me, the most interesting thing about Peachette is that she represents a version of Toad that is simultaneously the most powerful he’s ever been but also the most gendered.

Peach, after all, is a powerful character in the Mario series. She is the resident head of state, the target of Bowser’s ire and the focus of nearly every Mario game’s plot, but she’s also the series’ first female character and, as a result, the embodiment of femininity in these games. (It’s not nothing that the two next most popular female characters, Daisy and Rosalina, are visually based on Peach and still look a great deal like her.) If we can call Toadette a version of Toad, and I think we can, then there’s something provocative in his evolution taking Toad all the way to almost becoming Peach — and it’s especially notable considering those people who looked at the SMB-era sprite back in the day and wrongly decided that he was supposed to be female.

Peachette isn’t the handmaiden that people mistook Toad’s sprite for back in the day, but she’s something that lands close to that — a kinda-sorta doppelganger who stands in for Peach when she can’t be there, a lot like how those feminine-looking end-of-level Mushroom Retainers stood in for Peach in the original Super Mario Bros. Peachette might as well be saying, “Thank you, Mario! But our princess is in another castle… but also I’m here and I’m happy to just be the princess you want.”

I’d say Toad has come a long way, and that’s definitely true, but in this specific sense, Toad has really just come full circle. And this is just the latest example of how the gender dynamics surrounding this character aren’t just complex and interesting now but, really, have been from the start.

Miscellaneous Notes

If you’ve read all this and had the reaction of “okay, sure, but what about Birdo?” then you’re in luck! I’m going to do a deep dive into Nintendo’s treatment of Birdo’s gender — if not next, then very soon. I’ve also got something planned for those infamous field horsehair plants.

So why do we call the special end-of-dungeon captives Mushroom Reatiners? This is the word retainer in the sense of a dedicated employee or servant. Some people might hear that term and immediately think of samurai in the service of a shogun. That’s because the term is often used in English translations of 家臣 or kashin, a vassal in medieval Japan. However, retainer can refer to someone of any gender, performing all manner of service to a family. The term comes from an Old French verb meaning “to take into feudal service.”

One quirk to Toad’s status as both individual and species both, simultaneously, is that it doesn’t seem to be the case for Toadette and Toadsworth. When we see bustling towns of Toads, they’re usually single-color variations on *the* Toad, but we don’t see different-colored variations on Toadette walking around. She usually seems like the only one. Ditto with Toadsworth — all old Toads are not Toadsworth, but Toadsworth is an old Toad.

One result of Toadette being playable in New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe is that Blue Toad was minimized. He’s still selectable — both he and Yellow Toad are now just called Toad — but he no longer appears on the game’s title screen.

There’s actually some series-wide symmetry to this, as Super Mario 3D World features a playable Toad who is blue but not called Blue Toad. Presumably he’s in that game because Super Mario 3D World draws on a lot of Super Mario Bros. 2, and in the original NES version of SMB2, Toad’s onscreen sprite was all blue, rather than sporting a blue vest and a red-spotted mushroom cap like he was shown in official art. It remains to be seen how Nintendo would treat any of this in sequels to New Super Mario Bros. U or Super Mario 3D World, but for now it seems like a fairly even divorce: Blue Toad gets one subfranchise, Yellow Toad gets another.

In 2019’s Super Mario Maker 2, Toadette appears as both a cruel, anti-labor taskmaster and a playable character. She along with Toad — specifically one who is blue, a la SMB2, though not referred to as such — control identically to Mario and Luigi and even get throwback-style sprites that suggest how they would have looked had they been playable in SMB, SMB3 or Super Mario World. The play mechanics demand that these versions exist, of course, but on some level, it’s like Nintendo is retroactively atoning for the lack of a playable female character in all of these games.

I actually had every expectation that the Switch re-release of SM3DW would have featured Toadette added to the list of playable characters, but it actually didn’t happen, maybe because the storylines of Captain Toad and SM3DW overlap and it wouldn’t make sense to have her be in both. The next Mario platformer to be released, however? I’ll bet she’ll be there.

I didn’t want to fall into a giant Smurfs tangent, but yeah, there is more to differentiate Smurfette and Toadette, of course. But because someone will bring it up if I don’t say so, another major difference between Smurfette and Toadette is that the former was created by the evil wizard Gargamel, specifically to create discord among the male Smurfs. She does exactly that until Papa Smurf brings her over to the side of good.

In her debut, evil Smurfette was not yet blond. Read into that what you will. (Via.)

The Smurfs existed as a one-gender, all male species since 1958, when they debuted in Johan and Peewit, a long-running series also by comics writer Peyo. The characters proved successful, and Peyo spun them off into their own stories in 1959, and Smurfette didn’t appear until 1966. She stayed the one and only female Smurf — La Schtroumpfette, in the original French — until Sassette debuted in 1985, initially on the TV series and then retroactively in the comics as well. Toadette’s “braids” give her a passing resemblance to Sassette, I guess. There’s also a third female Smurf who appears in the cartoon series, Nana Smurf, who’s not given a specific origin and who doesn’t really have a Toad counterpart… unless you count the “grandma” from Super Mario RPG.

Toad’s Japanese name, Kinopio, is often considered a portmanteau of キノコ or kinoko, “mushroom,” and the Japanese rendering of Pinocchio’s name, ピノキオ or Pinokio. As near as I could tell, the character Pinocchio doesn’t have any special prominence in Japan compared to the U.S. or other countries that would explain why his name would be used as the basis for Kinopio. Translations of Carlo Collodi’s original 1883 children’s book, The Adventures of Pinocchio, were available in Japan going back to at least 1920, and of course the 1940 Disney film was translated and released in Japan as well, though not until 1952. I’d guess that someone figured out that transposing the syllables of Pinokio could make a handy mushroom pun. There’s an additional way the name works, however. Pinocchio’s name probably comes from the Italian words pino, “pine,” and occhio, “eye,” so there’s this sense of him being a piece of pinewood that comes to life. Similarly, Toad is a fungus that was seemingly brought to life. He is the Pinocchio of mushrooms, you could say. (No one says that.)

There’s an idea floating around online that Blue Toad and Yellow Toad actually do have names: Bucken-Berry and Ala-Gold. A 2009 Destructoid piece is the source of that, but it actually says the names were unofficial ones. If you ever hear people call them these names, this is why.

The Mario series would have been different if instead of inventing Toadette as Toad’s racing partner, Nintendo had plucked an existing character from obscurity. And really, they did have one in Wanda, the character who debuted in the 1993 Japan-only Mario & Wario. She’s actually the character the player controls in this game and is therefore the second playable female character in the entire series.

I actually always thought she reappeared in the 1994 Tetris-like puzzle game Wario’s Woods, but that’s actually a different (and apparently nameless) fairy character helping Toad. It would have made sense for Wanda to reappear, since this game features a host of second-tier Mario characters that Nintendo couldn’t figure out what to do with, most notably Birdo but also Toad and Wario. And it would make sense for Wanda to appear in the game because Mario & Wario already established that Wario is her enemy. Oh well.

Wanda, wand-toting fairy wearing a dopey red hat, from Maro & Wario.

And *not* Wanda, a different wand-toting fairy wearing a different dopey red hat, from Wario’s Woods.

And although Wanda appeared in various Mario merchandise released around the time Mario & Wario was released, she ultimately didn’t make the cut for later titles, save for as a spirit in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate. Alas. It’s always nice to have a female character in the mix whose signature color isn’t pink.

While Toad’s Mario Kart 64 voice was the one that turned heads and brought about that EGM article, he technically was first voiced years before the Nintendo 64 — in the Super NES version of Wario’s Woods. Here, Toad was given a voice wholly unlike anything he’d had in any other game. The especially odd part is that in a two-player match, in which the second player would control a green Toad, he was given a different, even more wrong-seeming voice. I’ll post them both here. Despite my best efforts to find out, I couldn’t determine who supplied either voice. But yeah, that Green Toad voice is… something.

Why do both of them say “breakfast”? I really couldn’t tell you.

Whether he’s called King Toadstool or the Mushroom King, Princess Peach’s father is a character that various Mario adaptations really wants to exist, I assume because it’s a way to explain why she’s only a princess if she’s the head monarch in charge. But no, I don’t think it’s likely that either Stop Watch or King Toadstool will be playable in a future Mario Kart installment. And if they do ever make the princess’s dad playable, I would hope they would go with the Lance Henriksen version from the 1993 live-action movie. It is interesting, though, that a Nintendo racing game that is not Mario Kart, Diddy Kong Racing, did feature a reasonable approximation of an in-game version of Stop Watch: T.T., a different and presumably unrelated sentient, talking, walking timepiece. You can actually unlock him as a playable character. Like Stop Watch, T.T. is also hideous to behold.

Other characters I’d wager won’t make it into a Mario Kart anytime soon? Probably not Wart, Tatanga, any of the Super Mario RPG crew, any of the WarioWare crew, Captain Syrup or Princess Shokora. Also, oddly none of the characters introduced in Super Mario Odyssey seem to have transitioned to spinoffs, which I think is super weird because there seems to be a lot of enthusiasm for those characters. (Please, Madame Broode would be the female heavyweight the series deserves.) I would say the least likely are male human characters like Stanley the Bugman. I’d put Foreman Spike on this list as well, mostly because the existence of Wario has more or less rendered him redundant, but then again he is appearing in the forthcoming Super Mario Bros. movie, and all it takes is one breakthrough appearance to make a forgotten character become relevant again. The one character to benefit from Super Mario Odyssey, after all, is Pauline, who is now playable in everything.

Long live the rainbow racquet!