Bahamut and Behemoth: One and the Same?

This is not an etymology blog. This is a video game history blog. However, in looking into the histories of things, we often end up examining the roots of the language we use to describe them. I think the intersection of the Final Fantasy versions of Bahamut, Behemoth, Leviathan and Kujata makes for a fun case study how language can evolve and mutate.

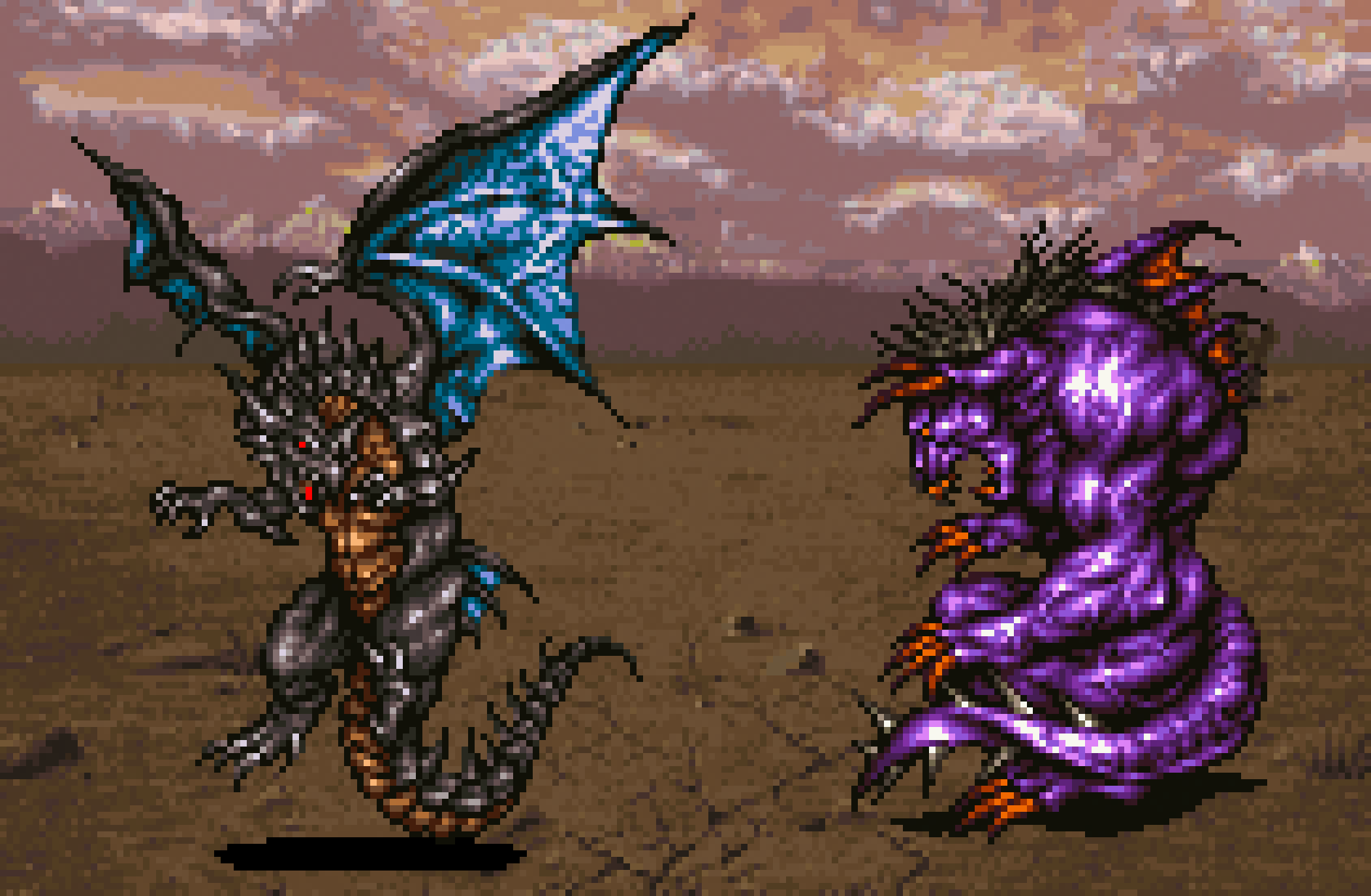

Bahamut vs. Behemoth: a battle for etymological supremacy.

In the world of the Final Fantasy games, Bahamut (バハムート or Bahamūto) is the king of dragons — a fierce beast whose favor must be won in order to get the benefit of his power. In the first game, he merely upgrades your party members’ classes when presented a notably mundane treasure: a rat’s tail. From Final Fantasy III onwards, Bahaut is a boss that the party must beat in battle before they obtain him as a summon.

Like many enemy characters in that first Final Fantasy, Bahamut was borrowed more or less directly from Dungeons & Dragons. Greyhawk, released in 1975, was the first supplement to the original Dungeons & Dragons, and it introduced a dragon king character. And then the first Monster Manual — released in 1977, in support of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, released the same year — gave this character the proper name Bahamut.

One of the ways that Final Fantasy seems to be using a character concept specifically lifted from D&D as opposed to, let’s say, a generic dragon who also happens to be named Bahamut, is the fact that the first game also features Tiamat (ティアマット or Tiamatto), a decidedly non-benevolent dragon and the fiend of wind. Bahamut and Tiamat don’t interact in the game itself, but they’re the two most prominent dragons in it, and also Bahamut is good while Tiamat is evil. This would seem to reflect an element of the D&D lore stating that Tiamat is the malevolent queen of dragons and Bahamut’s anthesis.

Even if that’s just a coincidence, however, D&D is also where the name Bahamut was first associated with dragons at all. Though I could not find any interviews explaining why, the name was borrowed from Islamic cosmological lore, from one of the names of the furthest-down entity in the chain of figures that hold up the world. According to the thirteenth-century Persian scholar Zakariya al-Qazwini in his treatise Marvels of Things Created and Miraculous Aspects of Things Existing (a.k.a. Wonders of Creation, but that title is nowhere near is good), the world is held up by an angel standing on a gemstone slab. The angel, in turn, rests on the back of an ox, which in turn stands on Bahamut (بهموت, pronounced “Bahamoot,” with the emphasis on the second syllable), a monster suspended in water.

In this illustration, (image via Wikipedia), Bahamut is depicted as a giant fish that is sometimes interpreted as a whale.

The scholars Yaqut al-Hamawi and Ibn al-Wardi give the name as Balhūt, and an alternate transcription gives the name as Bahamoot, but all versions of the name seem to correspond to another beast from Abrahamic scripture that should also be familiar to Final Fantasy players: the Behemoth. The Book of Job describes the Behemoth as being a powerful primeval monster, though one that walks on land and which is nothing like a giant fish.

[15] Behold now behemoth, which I made with thee; he eateth grass as an ox.

[16] Lo now, his strength is in his loins, and his force is in the navel of his belly.

[17] He moveth his tail like a cedar: the sinews of his stones are wrapped together.

[18] His bones are as strong as pieces of brass; his bones are like bars of iron.

[19] He is the chief of the ways of God: he that made him can make his sword to approach unto him.

It’s not clear if the animal being described is a real one or not. According to Etymonline, The Hebrew word בהמות (or b'hemoth) may be a “plural of intensity” of b’hemah, merely “beast,” but that Hebrew word might also be a folk etymology of the Egyptian loanword pehemau, literally meaning “water ox” but referring to the hippopotamus. (There exists the Russian word бегемо́т, or begemot, that also means “hippo.”) And while people supposing that the Book of Job is referring to a real-life animal have guessed that it might be a hippo, other guesses include rhinoceros, bison, or some kind of dinosaur.

In English, behemoth came to mean “a large or powerful thing” in addition to the Biblical monster, and I think it’s somewhere between that the recurring Final Fantasy monster exists.

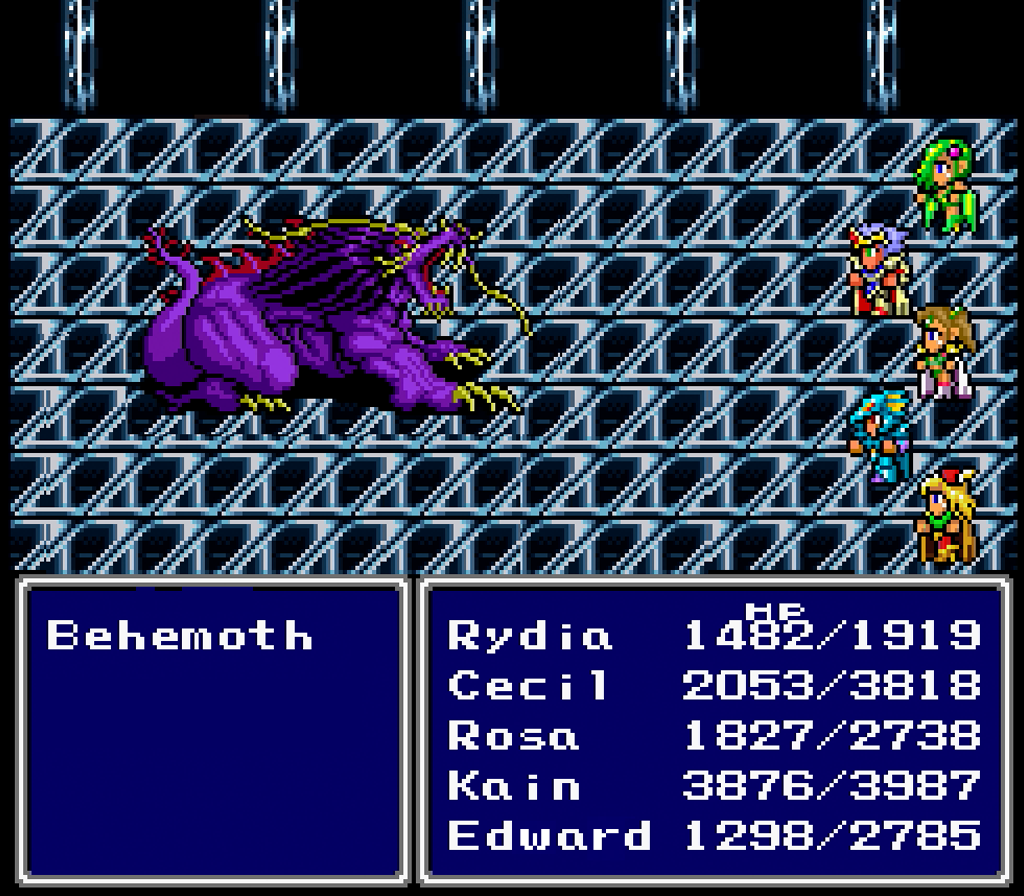

Fighting a Behemoth in FFIV’s Lunar Subterrane.

Although it does not appear in the original game, Amano artwork for it shows the Warriors of Light fighting a winged purple beast that eventually showed up in Final Fantasy II as the Behemoth (ベヒーモス, Behīmosu) and then in virtually every subsequent game, though without the wings. (That artwork would eventually materialize as the Behemoth King in Final Fantasy XV, wings and all.)

They’re popular and well-known enough that they occasionally show up in non-Final Fantasy games. An entire sequence in Live a Live, for example, focuses around an alien creature getting loose on a spaceship. It’s referred to in game as “the Behemoth,” and it looks almost exactly like the Final Fantasy version, just green instead of purple.

It’s an extraterrestrial because it’s a canon immigrant from Final Fantasy.

To answer the question posed in this post’s title, no, they’re not one and the same, but yes, there is an etymological link between the Final Fantasy versions of Bahamut and Behemoth. But isn’t it interesting that despite this shared source, one of these monsters was originally a giant fish while the other was clearly some kind of land animal? Well, here’s where it gets interesting — and we don’t even have to leave Final Fantasy lore to explore this connection further.

If you’ll recall, those scholars described the world being held by an angel, who is being supported by a large bovine, which is standing on the large fish. The bovine has a name too, though it varies according to who’s doing the translation. One name for it is Kuyūthā (كيوثاء), and it’s not merely a large bovine but often an inconceivably immense one, with eyes and legs and other body parts numbering thousands of times more than a typical bull or ox would have.

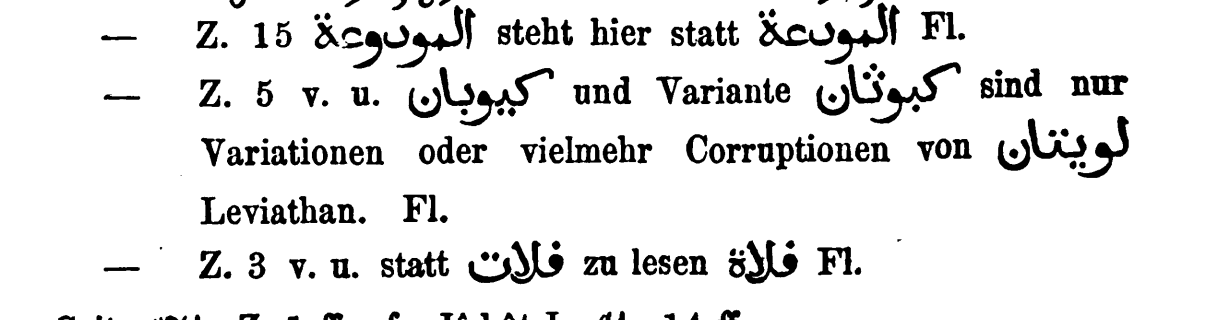

There are a lot of variants of that name Kuyūthā, two of which should also be familiar to Final Fantasy players. In al-Qazwini’s writings, the creature is also given the names Kīyūbān (کیوبان) or Kibūthān (کبوثان). Going back to at least 1868, with Hermann Ethé’s translation of al-Qazwini’s text into German, it’s been speculated that these names are “corrupted text” and that the reference was instead meant to be about Leviathan (לִוְיָתָן, Līvyāṯān), the demonic sea serpent that appears throughout the Bible but which is paired with the Behemoth in the Book of Job. (This version of Leviathan may be a manifestation of an older chaos deity that might have connections to Tiamat. More on that in the miscellaneous notes section.) In the world of Final Fantasy, Leviathan (リヴァイアサン or Rivaiasan) is a wholly separate character. Usually (but not always) male, Leviathan is the master of the sea who, like Bahamut, serves as a summon once defeated in battle. Though he appears in both Final Fantasy II and III, he’s a major character in Final Fantasy IV, where he destroys the party’s ship early on, before appearing again later as the king of Eidolons. It is definitely something more in line with the original sea monster sense of Bahamut than the benevolent dragon sense you see elsewhere in Final Fantasy.

However, in Jorge Luis Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings, that original name, Kuyūthā, was rendered as Kuyata in the Spanish and then as Kujata in the 1969 English translation of the Spanish. And that name has a presence in Final Fantasy as well: Kujata (クジャタ, Kujata) is a bull-like enemy that debuted in Final Fantasy VII. It also serves as a summon, and though it has recurred subsequently, it’s not as popular as Bahamut and Leviathan.

So looking at the mythology that inspired the Final Fantasy characters, we have two pairs of creatures: two water monsters (Bahamut and Leviathan) and two land monsters (Behemoth and Kuyūthā/Kujata). But if you pair them according to shared etymology, they split differently: on one side you have Bahamut and Behemoth and on the other it’s Leviathan and Kuyūthā/Kujata. How do we account for the fact that, at some point, a water monster became a land monster and vice versa?

Allegedly someone made a mistake, more or less. It’s been argued since at least 1961, per the Ars Orientalis article “The Iconography of a Kashan Luster Plate,” that the terms got swapped, with the error being indirectly blamed on the German writer Ferdinand Wüstenfeld. A footnote in the article explains, “The passage in [al-Qazwini] dealing with these ideas is [in] Wüstenfeld’s edition (where the names of the two animals are confused with each other and where the Leviathan appears in a corrupt Arabic form).” And that’s as solid an explanation as I can find: that someone, who may or may not be Ferdinand Wüstenfeld screwed up, and that mistake was recorded into the cultural record.

I would imagine it’s entirely possible that the mistake was made long before Wüstenfeld came along and that Wüstenfeld could have been accurately transcribing the mistake of someone previous, but that’s a matter for a historian with first-hand sources to determine. Being someone who speaks neither Arabic nor Persian, there’s only so much research I can do. Fatimah, one of two translators I work with on this site, is Kuwaiti/Irani and speaks Arabic. With the help of her mother, who speaks Persian, she looked into the matter but concluded, and this is a direct quote, “You, sir, need a scholar.” There probably is additional information regarding whether any text was corrupted or who in history swapped the terms and turned a water monster into a land monster. I am declining for the moment to bother anyone further with this, because let’s be honest: This is a site about old video games.

I wanted to write about the history of Bahamut because it illustrates how cultural drift can end up creating a thing in a video game that’s very far from its source material. As a result of a series of mistakes, shifts in understanding and some creative liberties, an unfathomably massive fish, conceived of centuries ago as the base upon which the very cosmos rest, morphed into the king of dragons in a series of Japanese video games. Not only did this happen, but in fact it happened so successfully that a simple search for his name yields more results for this newer incarnation than the entity it borrowed its name from in the first place.

This conceptual shift parallels the change you can observe in tracing the etymology of its name, where what might have been a loanword for “hippopotamus” came to refer to not only the cosmological fish entity and the king of dragons but also, as a result of time and space and maybe some kind of old world typo, a primeval monster in the Bible and another one in that same line of Japanese video games. Things change a little, then a lot, and soon you have an entirely new concept that owes its existence to the first one but also now stands on its own.

That’s wild, and while I never get tired of sorting all this out, it’s just as awesome to just sit here and observe that it happened at all.

Miscellaneous Notes

I’m going to continue to focus on Final Fantasy enemies that were drawn from D&D and then changed, whether as a result of a natural evolution or as a result of Square’s desire not to get sued for infringing on a copyright. (I haven’t written about how Square altered the design of one enemy after the original Japanese release of the first game, seemingly to avoid the danger of legal action, but I will get to it at some point.) In that vein, there’s a discussion to be had regarding how the D&D version of Tiamat has five heads. The Final Fantasy version, meanwhile, often has multiple heads — sometimes three, sometimes six, depending on the game, but often not five. Although Yoshitaka Amano’s concept art shows five, I wonder if the in-game sprite for that first game has six as a result of Square wanting to change the character design just enough to say, “See? Totally a different dragon, because different number of heads.” Curiously, the several ports of Final Fantasy II do show her with five heads, even if the original Famicom version only has four.

Because six heads are better than four.

Despite the similarity between the last syllables in Bahamut and Tiamat’s names, however, there doesn’t appear to be a shared etymology. Tiamat takes her name from a Mesopotamian sea goddess that is associated with primordial chaos and that is sometimes represented as a sea serpent or dragon. Her name allegedly traces back to tâmtu, an Akkadian word meaning “sea.” That said, both Tiamat and Leviathan are… related, in some way, whether as continuations or permutations, to older sea entities such as serpentine Lotan, from the Ugaritic series of stories about the god Ba’al.

So what’s the connection between Bahamut and the rat’s tail item you must present him in the first Final Fantasy? I don’t know, but I’m posting my best guess here in hopes that people will share theirs. The item itself is recurring in the series, but it it’s never associated with Bahamut again. The Japanese name, ネズミの尻尾 or nezumi no shippo, could mean “mouse’s tail” in addition to “rat’s tail,” but it doesn’t seem to imply that the item is anything other than that: a seemingly worthless thing that is nonetheless what the party must find in the Castle of Ordeals, a maze-like temple full of monsters and, in general, a real pain in the ass to venture through.

In that sense, it’s maybe ironic that there is this seemingly disappointing treasure waiting at the end of this optional dungeon that requires extra effort to conquer. However, there’s a radish, of all things, that bears some discussion in trying to explain the nature of this item: the rat-tail radish (Raphanuys caudatus). Found today in southeast Asia, it is believed to have originated in China, and the Chinese name for it, 鼠尾蘿蔔, literally translates as “rat tail radish,” and it gets this name because the edible root looks a lot like just that.

However, in other parts of the world, people saw this same vegetable and decided it looks like something else, because the same plant is known also as serpent radish or dragon’s tail radish. I don’t necessarily think this is what inspired the people at Square to invent an item that is associated with dragons and rats both. It might be more of a joke item — again, “ha ha, you worked hard and this treasure sucks, LOL” — but the fact that out of context a dragon’s tail and a rat tail could look a lot alike, out of context and disconnected from the animal that used to own it.

I suppose there is something minorly profound in that: a thing that might not seem special to you being exceedingly special to someone else. What might seem like a boring old rat tail to your Final Fantasy party is apparently something special to Bahamut, for reasons we may never know.

Here, for the record, is the footnote from Hermann Ethé’s translation of al-Qazwini’s original text that I believe is attempting to explain the confusion between the Persian words for Kīyūbān, Kibūthān, and Leviathan.

Do let me know if you can make sense of it.

I think this post has the record for the most languages mentioned so far of anything that’s gone up on this site. Nine, by my count.