A Short History of the Goomba

I was working on a post about how Super Mario Bros. 3 is the first Mario game to do self-referential stuff and call back to the series at large. In writing that piece up, what was supposed to be a single paragraph about the history of the Goomba just kept expanding — mushrooming, you might say.

For whatever reason, I try to keep the bits in the miscellaneous notes on the shorter side. Rather than chop any of this out, I figured I’d just toss up a mini post all about the lowliest character in the Super Mario games.

The story behind the Goomba’s Japanese name is complicated and seems confusing for non-Japanese people and Japanese people alike. The character’s Japanese name, Kuribō (クリボー), comes from the Japanese word for “chestnut,” kuri (栗), and bō (坊), an affectionate suffix essentially meaning “guy” or “boy.” If you are reading that and feeling surprised that the character’s name doesn’t mean “mushroom,” you’re not alone. However, people in Japan have always thought these little guys look like chestnuts. In fact, during a 2012 edition of Nintendo’s Iwata Asks feature, then-president Satoru Iwata was surprised to learn from Takashi Tezuka, senior Nintendo officer, that despite how he’d always viewed these characters, they’re supposed to be shiitake mushrooms.

Iwata: By the way, is it a coincidence that the Goomba looks like a mushroom?

Tezuka: It's a shiitake mushroom!

Iwata: It's a shiitake? (laughs) So it's not a chestnut?

Tezuka: That's right. (laughs)

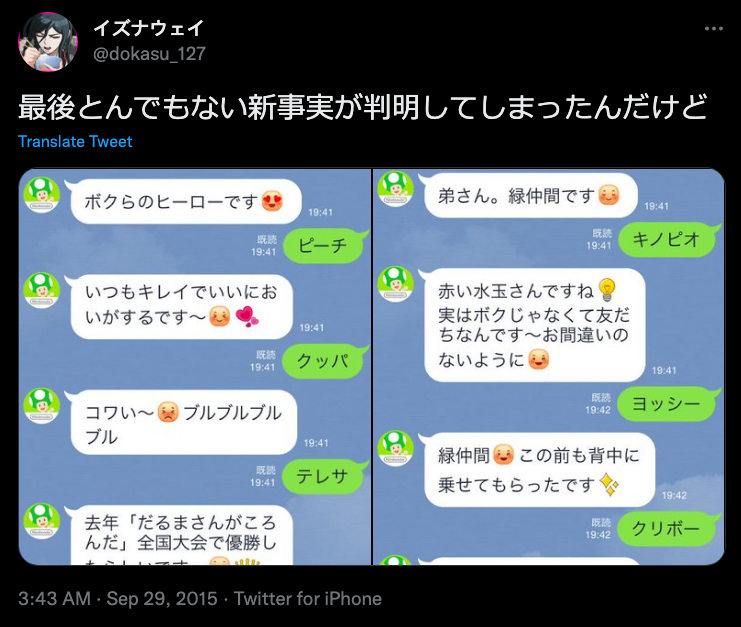

The fungal origins of the Goomba got a minor viral moment again in 2015, when an automated bot speaking as Kinopio-kun, the mascot for Nintendo’s LINE account, identified Goombas as being mushrooms and not chestnuts, to the surprise of some Japanese Nintendo fans.

If asked about various Mario characters, Kinopio-kun would give his opinion of them. For example, given the prompt of Mario, he’s say, “Our hero!” Given the prompt of Peach, he’d say, “Always beautiful and smells nice.” Given the prompt of Goomba (or, well, Kuribō, I guess), he’d say, “They’re not actually chestnuts. They’re shiitake mushrooms!”

According to Clyde Mandelin, the discrepancy exists because although Shigeru Miyamoto had always considered these characters to be evil shiitake mushrooms, a programmer working on the original Super Mario Bros. insisted that they looked more like chestnuts. The name stuck. As a result, a lot of Japanese players always saw them as chestnuts, even if the setting of Super Mario Bros. is the Mushroom Kingdom — in Japanese, Kinoko Ōkoku (キノコ王国). And even though the English name for the character, Goomba, doesn’t refer to mushrooms in any way, most of us just never thought of them as anything other than mushrooms.

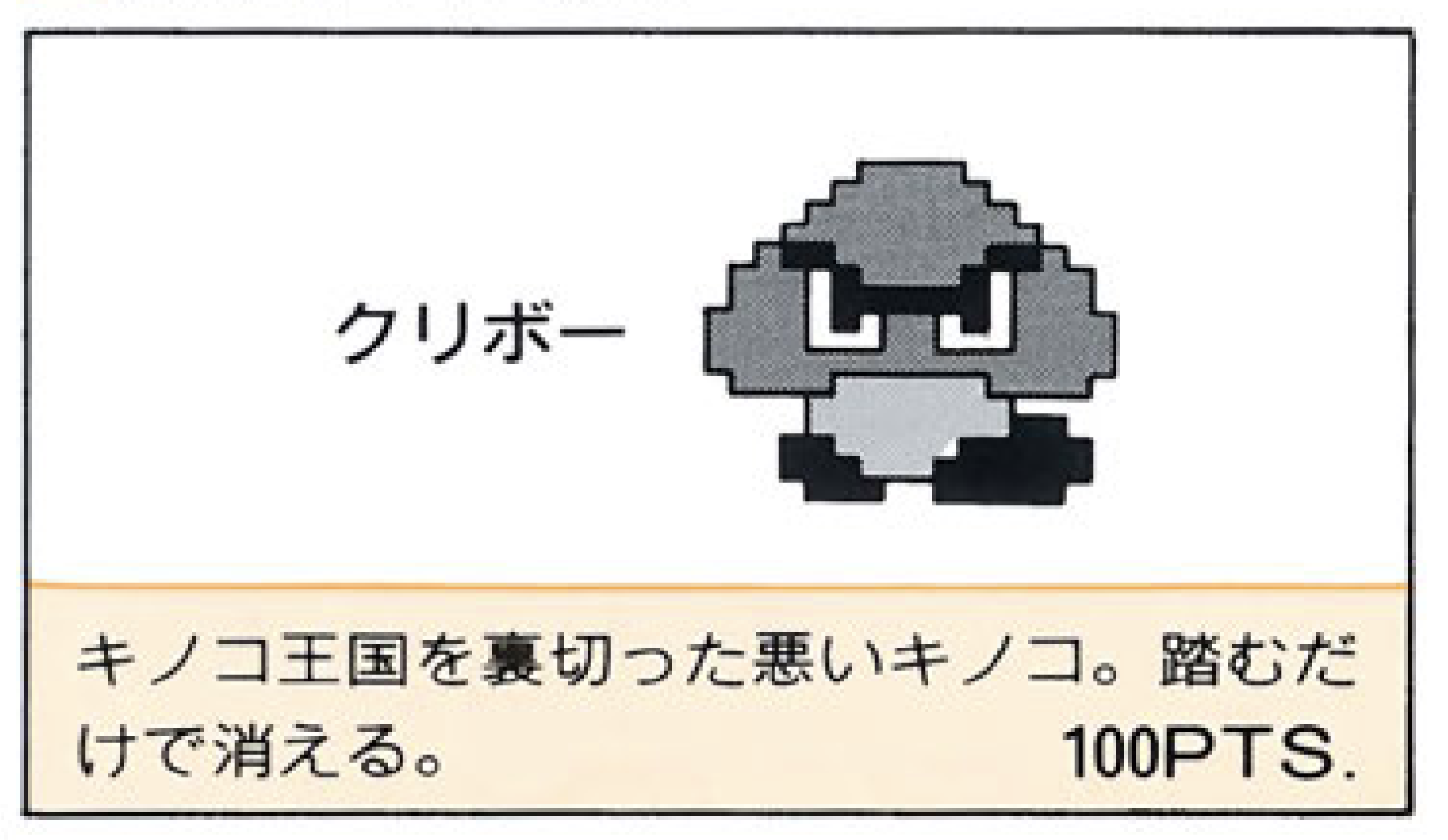

For what it’s worth, both the English and Japanese manuals explicitly identify these enemies as being mushrooms.

Translation: “An evil mushroom that betrayed the Mushroom Kingdom. One stomp and it disappears.”

I think this split shows how much room that chunky, back-in-the-day pixels left for interpretation. Like, we have chestnuts in the United States. Most kids playing Super Mario Bros. back in the day had probably seen a chestnut. But I don’t think anyone in the U.S. saw a Goomba marching toward Mario and thought, “Wow, look at that chestnut!” Even if we hadn’t read the instruction manual, it was generally a known thing that Super Mario Bros. took place in the Mushroom Kingdom. In Japan, the official materials did the opposite; even knowing the fictional setting where the game took place, players heard a character name that sounded like it meant “chestnut,” and as a result most were surprised to learn down the line that these little things were actually mushrooms.

The western name presumably comes from the Italian term goombah, a dialectical pronunciation of compare, “companion” or “godfather.” In fact, the linguistic process that turned that initial “c” sound into a “g” is the same one that made the cured meat known as capicola in some communities also known as gabagool in others, including the characters on The Sopranos.

I assume that Mario and Luigi being named in a way that suggests they’re Italian-American made someone at Nintendo of America pick an Italian-American term to rename this minor enemy character, though perhaps they weren’t considering all of the ways the word goombah can be used. It can be a term of affection among Italian-Americans, but it can also carry negative connotations — of mafia association, for one, or just as an outright slur for Italian people, depending on context. That considered, it’s actually surprising that the character name has endured, though I wouldn’t guess the etymology is at the forefront of most people’s minds when Mario is stomping these little guys.

(EDIT: There’s actually a pretty decent theory that the name could have come from an entirely different source, which I explain in this post.)

What is especially odd about the history of the Goombas is that in Super Mario World, Nintendo revised the character’s design to have rounder heads and no “stems,” making them look more like chestnuts, though I’ve never read an explanation from anyone who worked on Super Mario World about why this decision was made.

In the English version of the game, they’re just identified as Goombas, as if they were the same characters, even though they behave fundamentally different because Mario cannot stop them. In Japan, however, they’re Kuribon (クリボン) — presumably Kuribō with the suffix -bon (坊), which is actually the same suffix that is pronounced bō in Kuribō. Save for ports and remakes of Super Mario World, they did not return for nearly twenty-five years. Only with the release of Super Mario 3D World did they finally return, now referred to in English languages of the game as Galoomba.

Via BrotherBrain, clockwise from the top-left: the Goomba in Super Mario Bros, in Super Mario Bros. 3, in Yoshi’s Island and the thing we now call a Galoomba in Super Mario World.

As if to complicate matters further, a juvenile-looking Goomba character introduced in New Super Mario Bros. U, the Goombrat, is in Japan called Kakibō (カキボー), presumably a portmanteau of kaki (柿), “persimmon” and Kuribō. In Super Mario Maker 2, where the Super Mario World theme uses the chestnut-style Galoombas instead of the shiitake-looking traditional Goombas, the slot reserved for the Goombrat is given to a new character invented specifically for the game: a juvenile chestnut-looking guy called Goombud — Kakibon (カキボン), which is presumably Kakibō plus that suffix -bon again.

A subplot in the English-language version of Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door confuses Goombas and chestnuts, and to this day I’m actually not sure if it’s a mistranslation or if the localization was having fun with the ambiguity. Throughout the game, Mario encounters Luigi, who is having a parallel adventure that the player never sees but instead just hears about in installments from Luigi. This quest involves rescuing Princess Eclair from a villain the English version calls the Chestnut King but whom the Japanese version refers to as クリキング, or Kuri Kingu — which is the same name the Japanese version of the first Paper Mario gives to the Goomba King character. So it’s a character Mario has already met and defeated, but the way Luigi tells the story makes it seem like a separate character.

Goomba King? Goomboss? Or Chestnut King? All three?

To conclude, I give you one random Goomba-related factoid that I learned recently and I thought was neat. Returning to Paper Mario: The Thousand-Year Door for a second, Mario’s first companion character is Goombella, a sophomore archeology major whose studies allow her to inform Mario about various enemy characters he encounters. A recent post by Supper Mario Broth points out how this character actually fits into a pattern that exists only in the Japanese version of various Paper Mario sequels, where Mario’s main female companion is given a rather ordinary western name that is also a pun.

In Japan, Goombella is Christine — Kurisuchīnu (クリスチーヌ), a portmanteau of the common given name and Kuribō. Similarly, Tippi, the first Pixl companion Mario picks up in Super Paper Mario and the character that fulfills the same “tattle” function as Goombella does in Thousand-Year Door, is known in Japan as Anna — a pun on annai (案内), “guidance.” In Paper Mario: Sticker Star, the role is fulfilled by Kersti, who in Japan is Rūshī (ルーシー) or Lucy, effectively. It’s also a play on shiru (シール), “sticker” but literally the word “seal” rendered in Japanese. Finally, in Paper Mario: The Origami King, that role is filled by Olivia, whose Japanese name, Oribia, (オリビア), is a play on origami, with ori (オリ) meaning “fold.” As Supper Mario Broth points out, the pattern doesn’t work for when male characters fulfill this role; in the original Paper Mario, for example, the “tattle” companion is Goombario, whose name is seemingly a play on Mario’s own name and whose Japanese name, Kurio (クリオ), isn’t a common western given name.

Make of that what you will. I bring this up because it’s just generally interesting to me, and I can’t tell if I prefer this to be an intentional thing or an accidental thing, but also I want to call attention to the primo punning going on with Goombella’s Japanese name. Whoever named her, whoever was tasked with naming a female Goomba and realized that the western name Christine slid directly into Kuribō in a seamless portmanteau, did some masterful wordplay. I hope they got a raise.