A Short History of Street Fighter II Character Names

None of the Street Fighter II characters were created “just because.” Their looks, their fighting styles, and even their names exist for specific reasons — and often as a result of a few different pop culture entities colliding together and making something new.

This post initially started as an exploration of where Blanka got his name. In the beginning, I thought I had a decent handle on the origins of all the core Street Fighter II characters except for Blanka, and so I decided to research how Street Fighter II’s strangest character came to be. In doing that, however, I ended up learning a lot about the other eleven characters, including some “word of god” facts from the series creators that made me realize my personal headcanon was wrong. And please do note: Whenever possible, I tried to tie various presumptions, assumptions, and urban legends about this game and its characters to official sources, usually interviews with the Capcom staff that helped make the games. There are a few points where I am pretty sure that we have the accurate backstory but have yet to find a Capcom staffer speaking on the record about it. If someone reading this knows of an interview or the like that corroborates an as-of-yet unverified thing, let me know and I’ll update the post.

So yeah, I will get to Blanka — who, as it turns out, has the longest and most complicated backstory and might pull from more sources than anyone else in this iconic game, to the point that I decided to collect all of Blanka’s story into its own post. But first? Everyone else, starting with the original two Street Fighters.

Ryu and Ken

I should have known better, honestly. The context in which I learned this was a video arcade back in the ‘90s, and these places abounded with urban legends, often shared by some kid you didn’t know who was hovering over your machine and offering unsolicited information about the game you were trying to play.

This false bit of information was that Ryu and Ken’s names mean “dragon” and “fist,” respectively, and they’re both incorporated into the name of their iconic uppercut move, the Shōryūken. This seems reasonable enough. The Shōryūken (昇龍拳, “Rising Dragon Fist”) has been localized as the Dragon Punch, and on some level it’s probably as association Capcom wanted players to make, just mediated through the magic of homophones. The kanji 龍 does mean “dragon,” but Ryu’s name has a different origin.

The book The Art of Street Fighter features an interview with Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Matsumoto, co-directors of the original Street Fighter, in which they explain that Ryu and Ken’s names actually came from their own names. Nishiyama’s name, when written as 西山隆志, contains that kanji 隆, which can be pronounced the same as the kanji 龍, “dragon.” (Ryu’s name is usually written in katakana, as リュウ, but occasionally with the kanji 隆, which means “noble” or “prosperous.”) Ken, meanwhile, was originally going to be named Yū (ユウ), after an alternate reading of the kanji 裕, which appears in Matsumoto’s name, 松本裕司. It was eventually decided to switch Yu to Ken (拳, “fist”) — and I think we can be thankful this shift happened, because “Ryu and Yu” just doesn’t have the same ring to it.

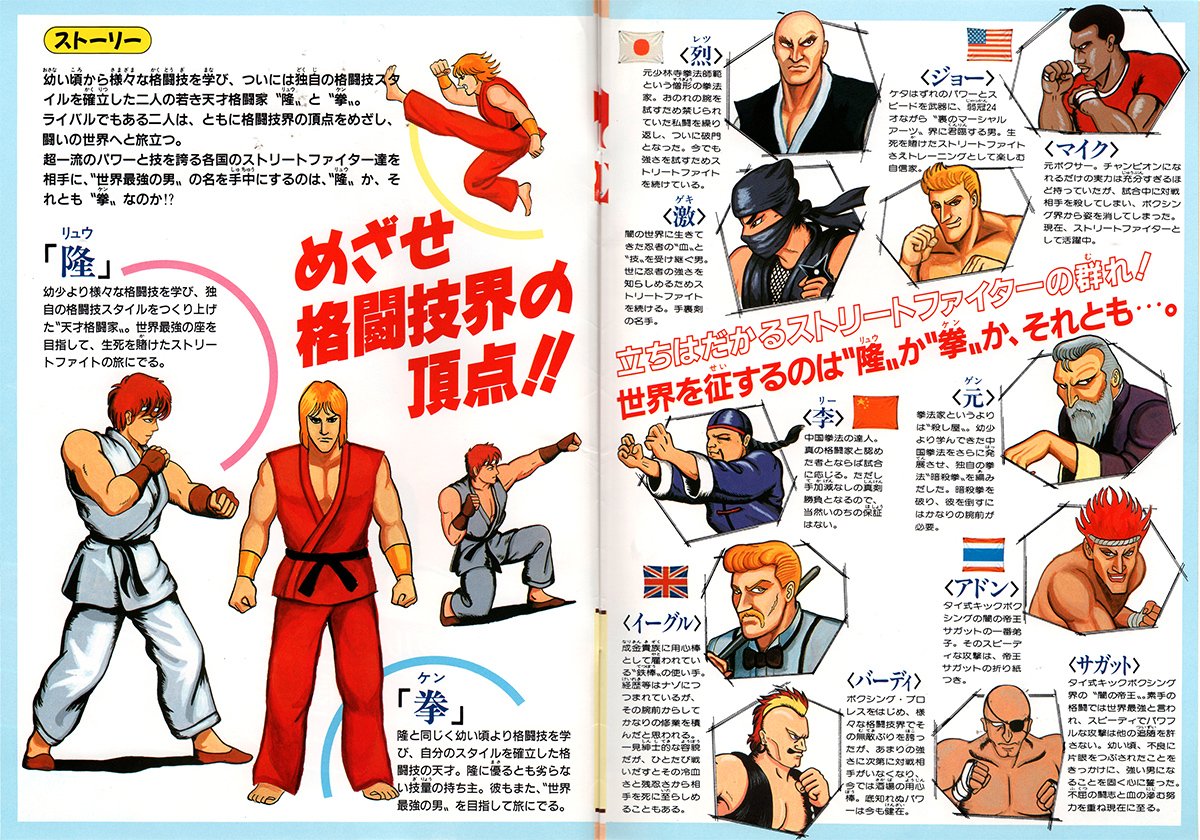

An official arcade booklet for the first Street Fighter shows Ryu and Ken’s names written with the kanji 隆 and 拳. Subsequently, Ryu’s name would be more often written in katakana and Ken’s almost always, especially after he got a last name. Scan via Retro Game Goods Collection.

Ken has a canonical last name, and his full name is name is written usually in katakana as ケン・マスターズ, Ken Masutāzu. There’s another commonly shared story for why Ken got a last name when most other Street Fighter characters don’t have one. We do know that he got his last name when Hasbro released a line of Street Fighter II action figures, and it’s stuck ever since, eventually becoming in-game canon. We don’t have an on-record reason why, although a fairly plausible two-part theory states that Hasbro did this to make the character legally distinct from a more famous doll named Ken — the one from Mattel’s Barbie line. So why Masters? Well, another toy line owned by Mattel is He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, so this could be an in-joke at Mattel’s expense — especially because Ken’s blond bob hairstyle looks a lot like He-Man’s. That’s just presumption from me and anyone else who has eyes, but it’s also far from the only time that Capcom has been cagey about why a certain Street Fighter character might be named the thing they’re named.

In researching this, I found a few sites claiming that Capcom switched the player two character from Yu to Ken as a nod to the protagonist in Fist of the North Star. That seems plausible, but I couldn’t find a comment from anyone at Capcom to back it up.

Guile

But then again, sometimes Capcom just comes out and says, “oh, the reason is this.” The September 25, 1998, issue of the Japanese gaming magazine Famitsu features an interview with longtime Capcom employee Noritaka Funamizu, who gives an origin for Guile’s name as well as how other characters were envisioned by the team before they were given proper names. He explains that Guile was the first of the new characters to receive a name because someone saw a sketch of him and decided he looked like JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure character J. Geil. The name stuck — even after it was revealed that this person misidentified the JoJo character, because it’s actually a different character, Jean Pierre Polnareff, that Guile looks like. Oh well.

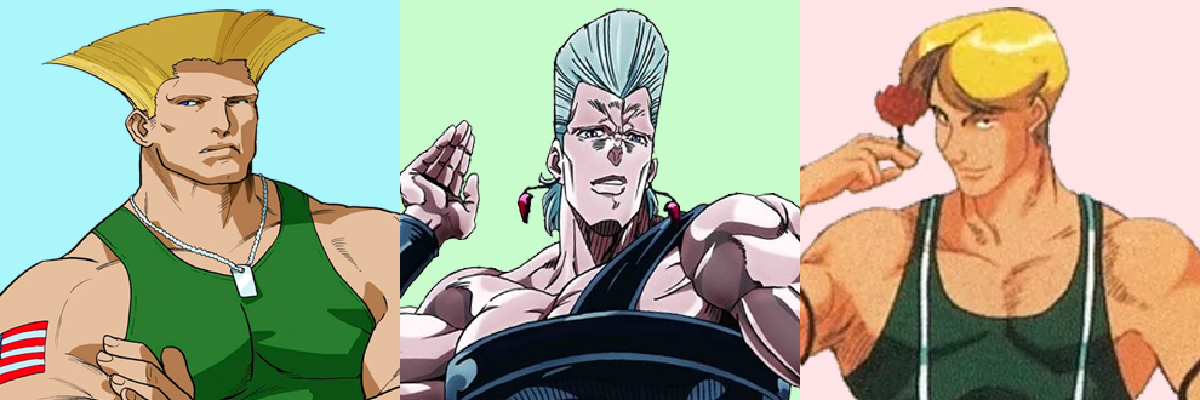

Left to right: Guile, Jean Pierre Polnareff from Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, and John Pierre from Fighter’s History. Not pictured: J. Geil from Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure.

Like so many characters from JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, J. Geil takes his name from pop music — specifically The J. Geils Band, of “Centerfold” and “Love Stinks” fame. That means Guile by extension also does, even if the English major in me wants to read commentary in a non-American company naming the representative for the U.S. military after a word that means “deceitful cunning.”

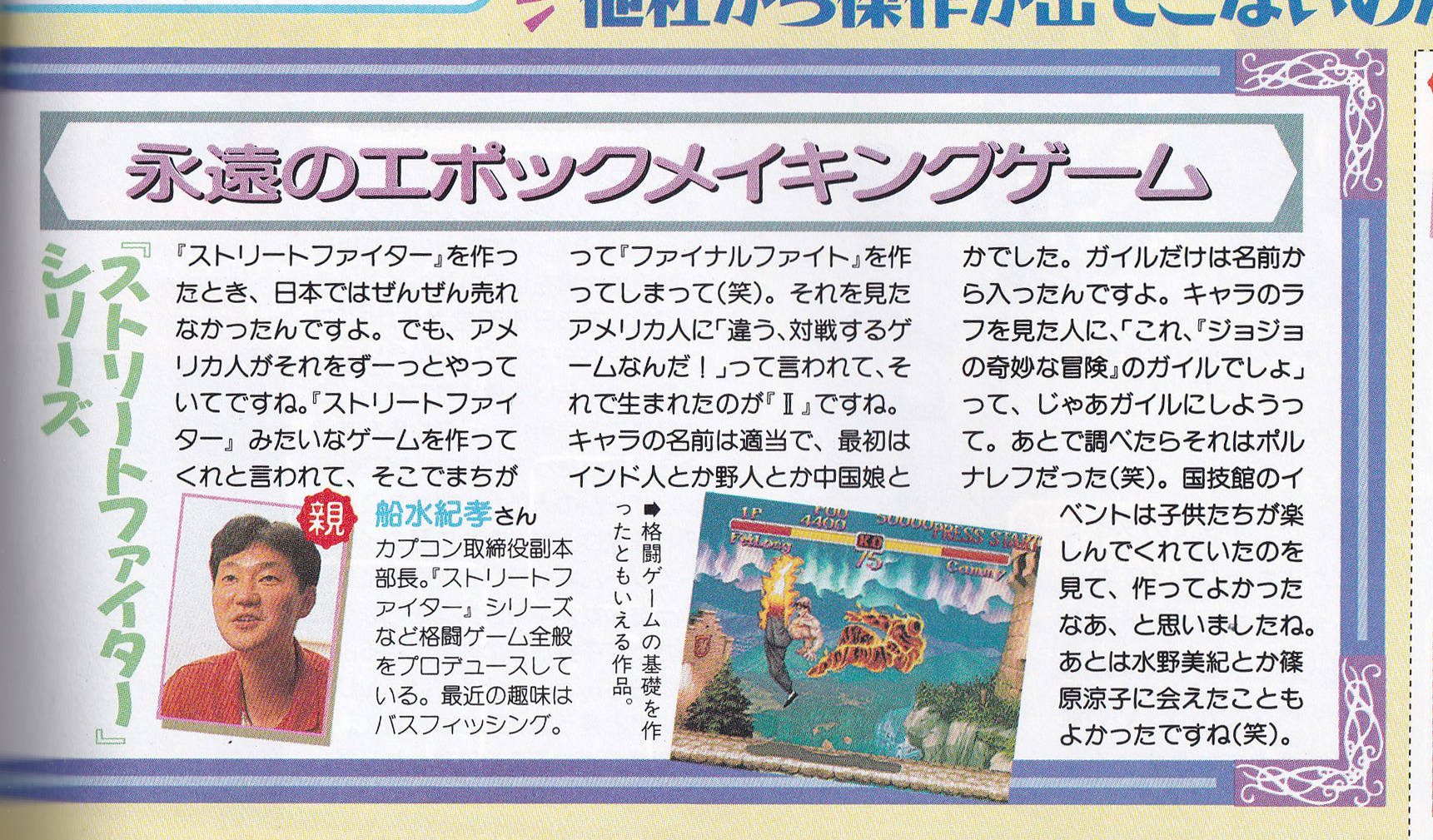

Translation: When we made Street Fighter, it wasn't selling well in Japan at all. Meanwhile, Americans kept on playing it forever. They were saying “Make a game like Street Fighter!” but then I made the mistake of making Final Fight (LOL). The Americans were like, “No! Make a competitive fighting game!” so then [Street Fighter] II was born. The character names were pretty random. At first, it was just stuff like “Indian,” “Ruffian,” or “Chinese Girl.” Guile was the only one with a name. Someone saw a rough sketch of the character and said “Isn’t that Geil from Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure?” So we just ended up going with that name. Later, I looked it up, and it turns out they were talking about Polnareff (LOL).

Famously, Capcom sued Data East in 1994 on grounds that the latter’s Fighter’s History video game infringed on the copyrighted Street Fighter characters and concepts. One of the perceived similarities is that Fighter’s History featured a French gymnast character who seemed a lot like Guile. That character’s name? Jean Pierre — the first name of the JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure character that inspired Guile.

Chun-Li

The same Famitsu interview has Funamizu stating that early on, the various other Street Fighter II characters were shorthanded as “Indian,” “Ruffian,” or “Chinese Girl.” This actually reflects what seems to be an underlying design theory for Street Fighter II: having fun with broad stereotypes. It’s perhaps an idea that lands differently today and perhaps didn’t land well back in 1991, depending on your personal views, but it’s also very much representative of video games in this era, as many other games played fast and loose with this kind of representation. (Pizza Pasta of Punch-Out!! comes to mind, among many others.) In 2014, composer Yoko Shimomura, who wrote most of the Street Fighter II themes, gave an interview explaining how this fundamental aspect of the game was expressed in the music:

When we were discussing the type of songs I should make, there were different scenes from different countries, but I thought, “The real India isn’t like this.” It’s the same way that Japan is geisha and kabuki from the eyes of foreigners. That kind of mysterious, distorted view of the world was funny to me.

We discussed the idea of — rather than character theme songs — maybe making background music with the feeling of each country instead. For example, for India I wouldn’t make real Indian music, but I’d make what I imagined Indian music to be like. When I suggested that making some kind of world music with a comical taste might be funny, they said it was fine, and we went with it.

“Chinese Girl” became, of course, Chun-Li (春麗 or チュン・リー), which in Mandarin means “spring beauty,” though some sources translate it as “beautiful spring.” (You could also translate 麗 as “lovely,” “graceful,” or “resplendent.”) As the original game’s sole representative of China but also the only female fighter, she was given a name that emphasized her femininity — and the fact that she has to be beautiful even in a martial arts competition. Akira Nishitani, one of the two lead designers on Street Fighter II, explained in a June 1994 interview in GamePro magazine that it was decided first the game should have a female fighter and only subsequently that this female character could hail from China.

via a scan at the Internet Archive.

In the Art of Street Fighter interview, Akira Yasuda is asked directly if Chun-Li’s design was inspired by Tong Pooh, one of three Chinese fighter sisters who debuted in the 1989 Capcom title Strider. “I think that’s a fair assessment to make. It was a time in history when you simply could not get by without a Chinese beauty,” Yasuda explains, referring to the fact that both characters are examples of a Chinese girl trope featured in video games and greater pop culture at the time. At some point in the planning process, the character was going to be named Zhi Li (智麗) and would have had an altered backstory making her the daughter of Gen, from the original Street Fighter and who’d later return to the series in Street Fighter Alpha.

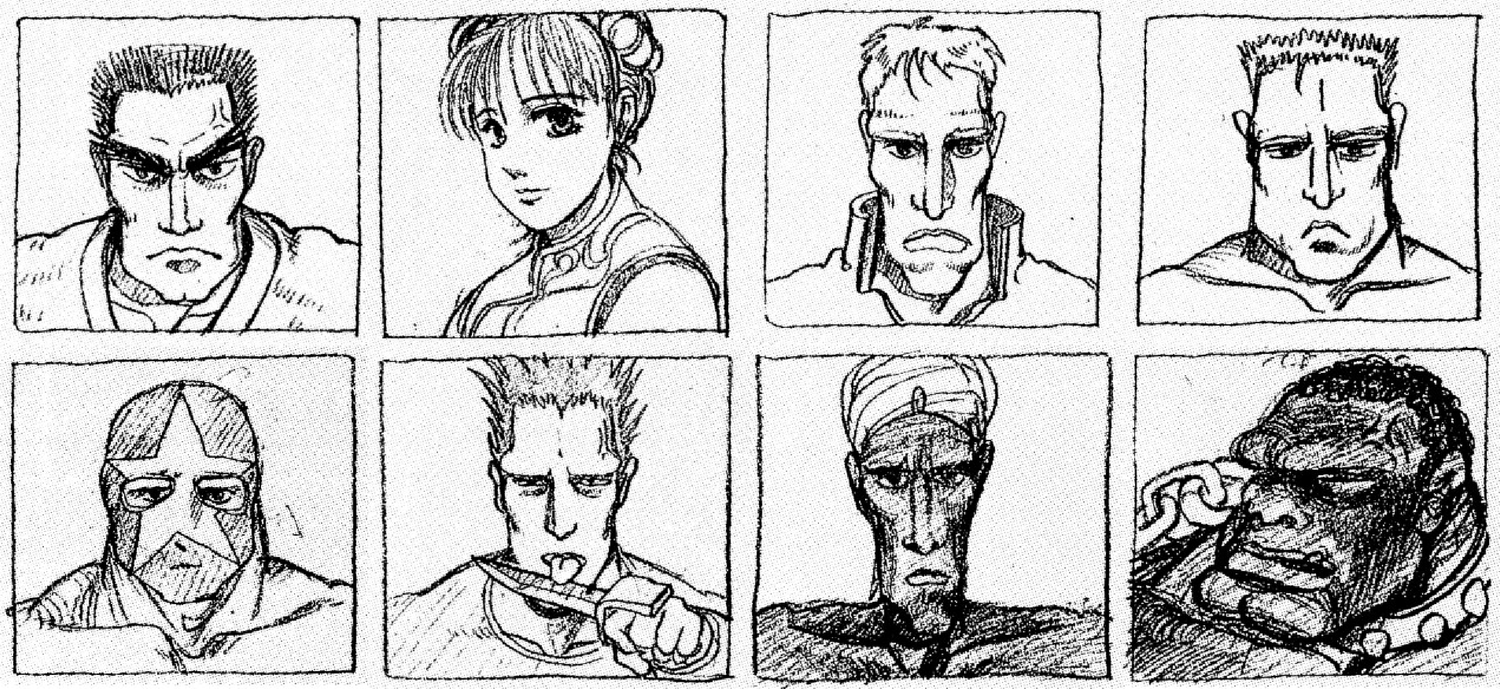

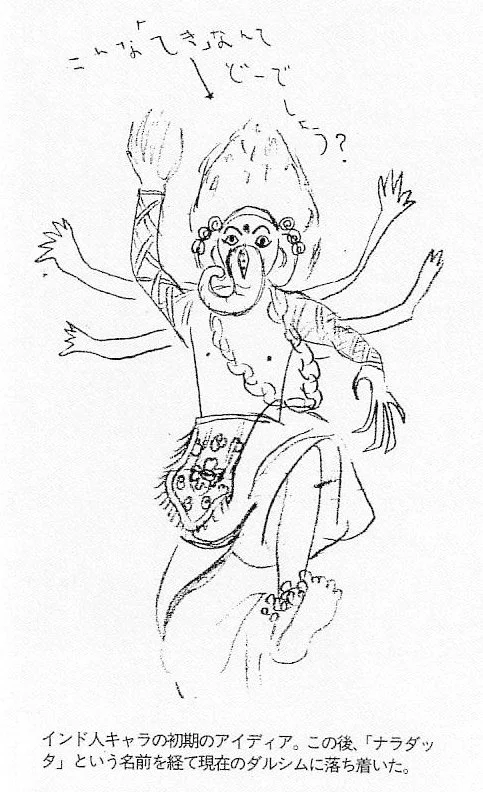

Per the Street Fighter II 30th Anniversary Collection, the original Street Fighter II combatants as they were initially conceived in 1988, two years before the game was released. Clockwise starting from top left: Masaaki Kakuda, from Japan; Zhi Li, from China, Bunbobo a capoeira fighter from an unspecified country; Dick Jumpsey, an American boxer and clearly a play on Jack Dempsey; Anabebe, an African fighter who evolved in Blanka and whom I discuss in greater length in the post all about Blanka; the Great Tiger; former green beret Shilke Muller, from an unspecified country and inexplicably seeming like a play on the female German athlete Silke Möller; and Tahir Meyer, a masked wrestler from an unspecified country. Yes, the original line-up did not include Ryu or Ken.

Translation: “2. Zhi Li / Chinese Kenpo Practitioner / 18 years old / 164 cm / 48 kg. A female kenpo prodigy. Practitioner of the Northern Praying Mantis style. Took the Chinese martial arts scene by storm and became an idol overnight. She is actually Gen's daughter, and she entered the tournament to find the man who killed her father. Her body is extremely limber, so she attacks with a unique style. Special move: Hair Attack.

In the Art of Street Fighter interview, Nishitani says there was a real-life inspiration for Chun-Li’s name, but he does not name that specific person.

I was flipping through a Chinese martial arts magazine when I saw a person with a similar name. It was Chinese, and I had no idea how it was supposed to be pronounced, so I just guessed it to be “Chun-Li.” Then we simply picked out nice-looking kanji that would phonetically fit that name.

Left to right: Chun-Li, Tao from Harmageddon: Genma Wars, Angela Mao in Lady Whirlwind and Tong Pooh from Strider.

In the 1975 Hong Kong martial arts film Lady Whirlwind, Angela Mao plays a female fighter named Tien Li-Chun, but I can’t find any Capcom representative commenting on this being an inspiration for Chun-Li’s name. It may be a coincidence. A 2003 interview with Capcom artist Akira “Akiman” Yasuda cites the original inspiration for Chun-Li as the Chinese character Tao from the anime Harmagedon: Genma Wars, with “big, wide-legged pants.” He goes on to explain that he struggled to find a balance between sexy enough and fearsome enough.

First I tried giving her bare legs and a bodycon dress. That made her look like a female pro-wrestler, a sort of “fake” kung-fu fighter. It’s a little bit hard to describe in words, but it had a lot of impact, and I decided to go with it and release her to the world this way. She became far more popular than I had imagined, I was shocked. I guess part of it was that she was the only female character in the game.

Balrog, Vega and M. Bison

If you ask a fan of Street Fighter what they can tell you about the history of character names in the series, they’d probably be able to tell you how three of the four bosses in Street Fighter II swapped names, which is why the end boss is named M. Bison even though bison are American bovines that are known for being large and strong but not necessarily evil or ferocious.

If you ask a nerdier fan of Street Fighter, they might also tell you the reason behind the swap allegedly stems from Capcom’s fears that real-life boxer Mike Tyson might sue over his likeness being used in the form of the game’s boxer character — M. Bison in Japan, but Balrog in the U.S. and other territories. In a roundtable discussion sponsored by Capcom for the fifteenth anniversary of Street Fighter II, composer Mitsuhiko Takano explains this to fellow Capcom music folks Isao Abe and Yuko Komiyama (a.k.a. Komio) while also noting that decision-makers at Capcom, Vega made for a good final boss name in Japan but not in the U.S. And in a 1991 Gamest magazine special on Street Fighter II, Nishitani outright says one of the reasons Vega didn’t work in the west was that outside Japan, it sounded feminine — bad for a supreme villain, perhaps not inappropriate for a beautiful man whose obsession with his appearance codes him as feminine.

As a result, the American translation of the game gave the boxer’s name to the dictator character previously known as Vega, whose name was then given to the matador. Perhaps that was fitting because vega actually is a Spanish word, if one that doesn’t have a particularly exciting meaning, and also a non-uncommon Spanish surname, but it’s also the brightest star in the constellation Lyra, which also befits the fighter who would certainly see himself as the brightest and most beautiful in the game. And if the name Balrog comes from the powerful monster from Lord of the Rings, then it’s not a bad name for the hulking, brutish boxer character who is, as far as Capcom U.S.A. is concerned, not based on Mike Tyson in any way.

Translation:

Abe: Then, did you know that Vega and Bison's names are the opposite overseas? There are all kinds of connections.

Komio: Hm, nothing comes to mind...

Abe/Takano: (LOL)

Takano: In other words, Bison was a character based on Tyson, and if we made his name Bison, it would be an infringement of rights due to the likeness of the real person, so the name was changed to Balrog, and we changed Balrog to Vega. And Vega means… Lyra, I think? So, from the Japanese point of view, the name Vega might seem cool for the last boss, but from the foreign marketing point of view, it’s “lazy.”

Komio: Oh?

Takano: So we named the neutral Balrog, Vega. And since Sagat has been Sagat’s name since Street Fighter I, we couldn't change it, so we decided to name the last boss General Bison.

Komio: How complicated.

Takano: (LOL)

Abe: So that's why in the movie it’s General Bison.

Takano: By the way, how excited was your company at the time when your game was being made into a Hollywood movie?

Abe: Uh, well, there was no particular excitement... At that time, the hype around Street Fighter II in Japan had already calmed down. I think there was more of an atmosphere of “they’re doing that again” within the company (LOL).

And one time I was talking to someone who is an even bigger Street Fighter fan than I am, and that’s who pointed out to me that the entire reason for this name swap was purely economical. Rather than give any characters new names that would require a new recording by whoever did the announcer voice, just sliding the names around fixed the lawsuit problem as well as the one involving Capcom U.S.A. thinking that Vega just wasn’t badass evil-sounding enough for the end guy in a fighting game, though I think my complaints about bison stand. It’s a rather elegant solution to two different problems, when you think about it.

For the record, Capcom considers Barlog (formerly M. Bison) to be a separate character from Mike, who appears in the first Street Fighter and who is a black boxer who also seems to be inspired by Mike Tyson. One of Barlog’s endings in Street Fighter V actually makes a joke about the similarity.

And yes, BTW, Mike Tyson is aware of his Street Fighter connection.

According to this interview, in the earliest stages of production, the working name for the dictator character was Washizaki (鷲崎, “eagle cape”), after a villain from the manga Riki-Oh who clearly influenced the Street Fighter character’s design.

Zangief

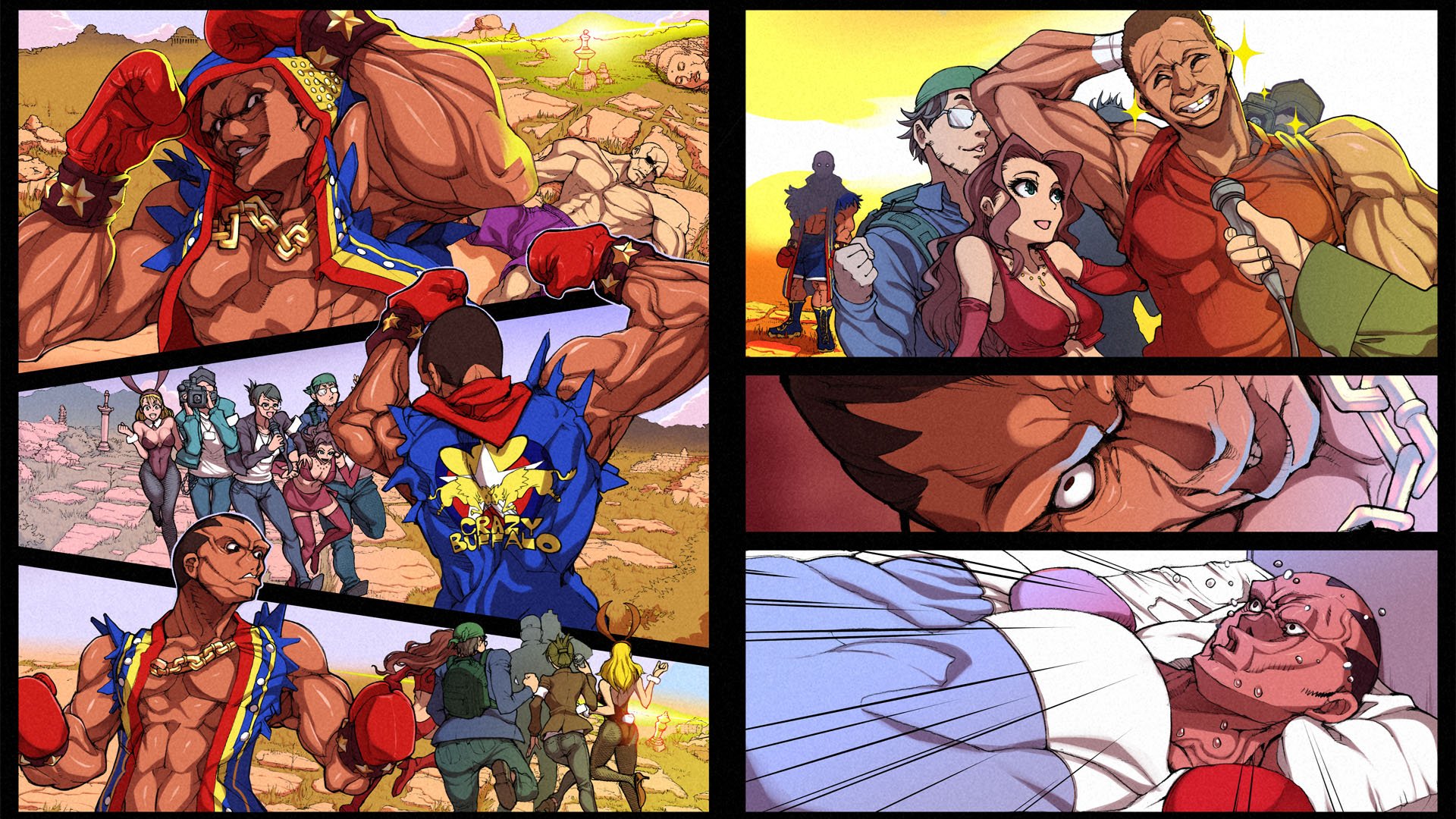

The character who’d eventually become Zangief was at one point called Vodka Govalsky — a name sometimes also rendered as Vodka Gobalsky. According to the Street Fighter 30th Anniversary museum, this name was “never seriously considered for the final game.”

Translation: Hates communism, and participates in Street Fighter for the money. He’s in it for the money again this time.

Vodka Govalsky

Large pro wrestling fellow

Fought matches without really understanding things like rules and tact. All of his opponents were left in states beyond recovery. As a result, he was banished from the world of wrestling. Now, he’s working to revive the underground pro wrestling scene.

Zangief’s appearance and moves seem like they’re borrowed from several pro wrestlers, Russian and otherwise, who would have been active around the time this character debuted, his name seems almost unmistakably a reference to the real-life Ossetian wrestler Victor Zangiev. I cannot find any interview where a Capcom employee has confirmed this, but then again the whole M. Bison kerfuffle might explain why no one has, even all these years later.

The real-life Zangiev’s Wikipedia page says he’s the inspiration, but the claim is missing a citation.I checked the talk page of Zangief’s Wikipedia page to see if anyone was discussing this, and the answer is no, but the debate over whether Zangief is gay is lenghty, spirited, and ongoing.

Sagat

Similarly, the big boss muay thai fighter Sagat seems to draw inspiration from various fighters — some real, such as Dieselnoi Chor Thanasukarn, some fictional, such as the character Reiba from the manga Karate Master/Karate Baka Ichidai. However, his name seems to be a fairly clear reference to the real-life fighter Sagat Petchyindee, to the point that this 2016 Bangkok Post article about him just leads with the Street Fighter II connection.

E. Honda

While Ryu is a Japanese character who is also the protagonist of the series, E. Honda makes more sense as a Japanese stereotype along the lines of the other characters introduced in Street Fighter II. He is a sumo who fights in a traditional bathhouse and sports a face full of kabuki make-up. Even his last name is a nod to the Japanese auto manufacturer — to the point that in the planning stages his name was E. Suzuki, namechecking a different auto company based in Japan but with a worldwide presence. According to a 1991 Gamest special issue on Street Fighter, Tanaka was also considered for his name.

Given all that, it may seem counterintuitive, then, that he’d seemingly be given a non-Japanese first name: Edmond. That, at least, is how English versions of the game represent his Japanese name, エドモンド 本田, Edomondo Honda — first name before last name, non-Japanese-style, and with his first name in katakana and his last name in kanji, though some sites represent his first name with the kanji 江戸主水. The obvious explanation is that Mr. and Mrs. Honda just chose to give their son a non-Japanese name back in the day, but given the fact that most Street Fighter II characters are named for a specific reason, it does seem strange. One theory is that his first name is a nod to Edo (江戸), the historic, former name of the city of Tokyo. That also might just be a coincidence, especially if Capcom picked this name for a completely different reason.

In the thirtieth anniversary book Street Fighter Memorial Archive: Beyond the World, there’s an interview with Akira Yasuda and Capcom artist Bengus that reveals E. Honda was to some degree inspired by Mr. Yunioshi, the egregious yellowface caricature Mickey Rooney played in the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s — and I gotta say, this is a reference I did not think I’d be making in a write up on the history of Street Fighter characters, yet here I am.

Yasuda: Edmond Honda was inspired by that phony Japanese guy who lived upstairs in the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s. You see that stuff a lot — weird decor and “samurai” that show a misunderstanding of Japanese culture. As far as video games go, there was a sumo wrestler enemy in Ninja Gaiden.

Bengus: Did that come first?

Yasuda: Yeah. After that, it was like I had no choice but to put a sumo in. I liked it too much; I love that fat guy who comes charging at you.

Bengus: There was one in basically every Capcom game around that time: a fat guy who comes charging at you.

In the end, Honda ended up representing a grab bag of traditional Japanese traits, which isn’t exactly as Yasuda describes Mr. Yunioshi, but I do wonder if Sodom — the Final Fight import who joined Street Fighter with Street Fighter Alpha and one of the biggest weebs in video games — ultimately inherited the notion of colossally misunderstanding Japanese culture.

Dhalsim

At the top of this post, I said that Blanka has the longest and most complicated history of the original Street Fighter II characters. Dhalsim is a close second, and as of now both theories I’ve found are somewhat lacking.

The most popular theory on the English-speaking internet — posted on Dhalsim’s Wikipedia page, though not citing any source — is that the Indian fighter is named after an Indian food restaurant near Capcom’s office in Osaka. Allegedly, the first syllable comes from the dish usually made with lentils and the second comes from the hyacinth bean, which is known by a bunch of different names all over the world, including some represented in the English alphabet as sheem, seim, shim and the like. This doesn’t seem unreasonable, considering where other Street Fighter names have come from, but I can’t find any instance of someone from Capcom vouching for it. It could just be a coincidence that Dhalsim’s name resembles the names of these two Indian dishes mashed together. A similar theory states that Dhalsim’s name comes from one of several Indian restaurants near Capcom’s headquarters in Osaka, and while I couldn’t find anything to back this up, I have made a discovery about Blanka’s origins (explained in part two) that makes this seem ever so slightly more plausible.

A more credible theory comes from Akira Nishitani, speaking in an October 1991 special issue of Gamest Magazine focused on Street Fighter II. He says that Dhalsim takes his name from Dhalisma, a real-life martial artist from the “India-Pakistan area,” in addition to giving some further explanation for some other naming decisions.

From page 88 in the Gamest special on Street Fighter II. Translation:

Nishitani (NIN): Dhalsim’s name was taken from Dhalsima, an actual fighter from the India-Pakistan area.

Akemi Kurihara: That kind of thing sounds fake even though it’s true.

Nishitani: Zangief is the same. He’s based off a Soviet pro wrestler. This is the pattern we used. We wanted to give E. Honda a Japanese name. First, we thought something like Suzuki or Tanaka, but we figured westerners are more familiar with Honda. Balrog seemed really strong, so we gave him that name. Vega gives off a strong feeling in Japan, but in America, it’s Virgo/the Virgin and has a feminine image. This was pointed out to us later on.

Kurihara: In the overseas version, Bison’s name is different.

Nishitani: Well, Bison is too similar to Tyson and we could get into trouble. Things can be pretty strict over there.

The problem with this theory is that I’m not sure what real-life martial artist Nishitani is talking about. While Dhalsim’s name is rendered in Japanese as ダルシム (Darushimu), this real-life person’s name is allegedly Dhalisma, which is rendered in Japanese as ダルシーマ (Darushiima). I’ve looked online for who this person could be and have so far found nothing. Perhaps someone more familiar with martial artists from this part of the world can figure it out, though surely Dhalsim ended up being inspired more by the stretchy-limbed Indian fighter in the 1976 wuxia film Master of the Flying Guillotine than any real-life person whose limbs probably don’t stretch as much.

A scene from Master of the Flying Guillotine (1976) featuring Wong Wing-Sang as Yogi Tro Le Soung, a stretchy-limbed Indian fighter.

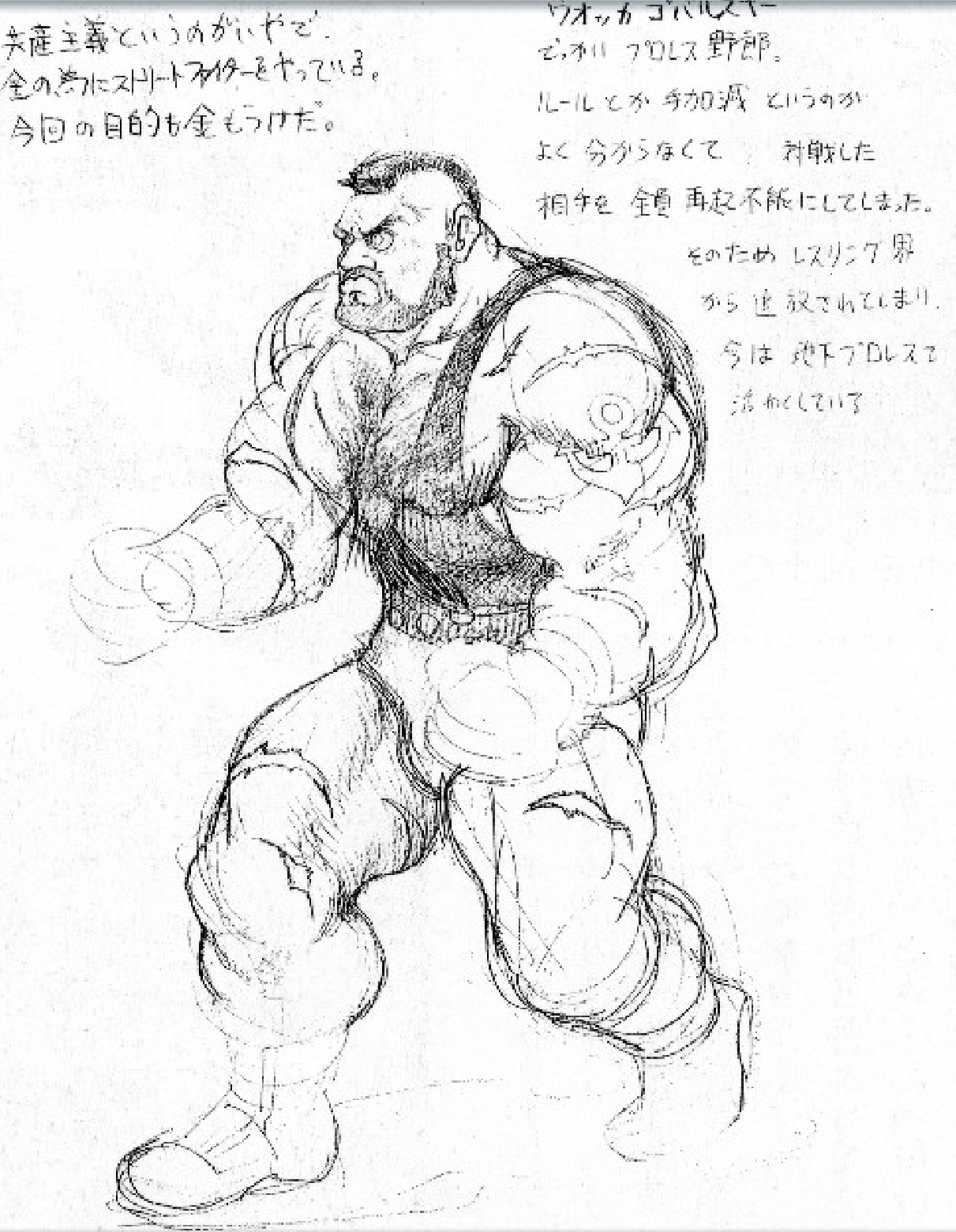

Translation: How about an enemy like this? An early concept for an Indian character. They were known as Naradatta but then it gave way to the current Dhalsim.

According to this 1991 interview with Akira Nishitani, when Capcom was considering using an elephant-headed design resembling the Hindu god Ganesha, the name Naradatta was attached to the character. It’s possibly an allusion to a character in the Osamu Tezuka manga Buddha but also a name with relevance in Buddhism. Perhaps not coincidentally, Dhalsim’s son is named Datta. Another early design for Dhalsim was an Indian fighter wearing a turban and going by the name Great Tiger, which is the exact name and design of the Indian boxer in Super Punch-Out!!, which debuted in arcades in 1984.

Miscellaneous Notes

Though there are probably a lot of stories to be told about all the other Street Fighter characters, I tried to stick to just the original twelve. This post was already long enough as is, but I do have a quick note about Cammy. Her name was apparently Sarah at some preliminary stage. The working theory is that Capcom altered her name to avoid similarity with Sarah Bryant from Virtua Fighter. Both Virtua Fighter and Super Street Fighter II hit arcades in October 1993, and on top of having the same name, they’re both brainwashed blondes. Weirdly enough, 1994 would see the debut of Tekken and its character Nina Williams, a third brainwashed blond fighter.

Because it’s a connection that has recently come up in the news, I also have a bit about Fei Long. It’s probably a coincidence, but there’s some nice symmetry in Hong Kong action star Fei Long joining the stable of playable characters in Super Street Fighter II. His name (飛龍) means “flying dragon” in Cantonese, which puts him in good company with series leads Ryu and Ken, whose signature Shōryūken move means “rising dragon fist.” That is, both the old guys and the new guy have this symbolic connection to dragons moving through the air, more or less. If anything, it’s just an added bonus, however, as Fei Long serves as an extended homage to real-life Hong Kong action star Bruce Lee, and Lee’s Chinese stage name was 李小龍 (Lee Siu-lung in Cantonese and Li Xiaolong in Mandarin), which means “little dragon.” At the time this post went live, the Bruce Lee connection was the subject of a news story about Capcom allegedly retiring Fei Long as a result of the company’s skittishness about similarities between its characters and real-life people. It remains to be seen whether Capcom truly has retired the character, however.

Alph Lyla (アルフ・ライラ) is the name of Capcom’s “house band” featuring the company’s composers and sound designers performing covers and reinterpretations of game music. It’s possible the name may connect with Capcom and Vega in particular. In addition to being a boss in Street Fighter, Vega is also the brightest star (or alpha) of the constellation Lyra, which is supposed to represent the lyre of Orpheus, the greatest musician in Greek mythology. That was my initial guess for where the name could have come from, but then a reader posted a comment noting that the Arabic title of A Thousand and One Nights is Alf Laylah wa-Laylah, which seems like a more obvious connection, with my guess being a fun etymological bonus. And why yes, there is a Street Fighter II image album by Alph Lyla.

The ditched backstory for Chun-Li — when she was Zhi Li, and she was going to be the younger relative of a character from Street Fighter I — ended up being reused in Street Fighter III, in a sense. That game introduced twin fighters Yun and Yang, who are the nephews of SFI’s Lee. SFIII also introduced Ibuki, who back in the day was presumed to be a relative of SFI’s Geki, but that’s proven not to be the case.

This post was focused on name origins but mentioned more than a few inspirations for the looks of various Street Fighter characters. The best compilation of these visual homages is on the website Fighting Street. It also points out some name stuff, like Poison being named for the rock band and her counterpart Roxy being named for Roxy Music, which cites me as the source of that, which is a thing I do not remember saying. The internet is super weird.

That’s it for this round-up of Street Fighter II character origins. If you want to know about the long, complicated road to Blanka, continue on to the second part of this series.