Did Super Mario Bros. 3 Change Our Understanding of the Tanuki?

I think I can point to the single moment when I realized that video games were teaching me about Japanese culture.

Around 1992 or 1993, I rented Pocky & Rocky from my local video store. This Super NES game is thoroughly steeped in Japanese mythology, but the thing that stuck out to me at the time were these one-eyed umbrella enemies. They’re based on a creature called kasa-obake in Japan, but I didn’t know that at the time. I only knew that I’d seen something remarkably similar in Super Mario Land 2, where one of the areas Mario has to hop through is Halloween-themed and populated with various pop culture monsters: witches and vampires but also these similar-looking umbrella monsters.

Left: The one-eyed, sandal-wearing umbrella monster from Pocky & Rocky. Right: The peculiarly similar one-eyed, sandal-wearing umbrella monster from Super Mario Land 2.

And that’s when I realized that because Mario and Pocky & Rocky were two unrelated franchises made by two separate companies, I was probably seeing something that existed outside video games. These bouncing, one-eyed umbrellas were something older, and some audience somewhere would recognize them in the way I did the beanstalks and magic carpets in previous Mario games, as not a Mario thing but just, like… a known cultural thing, more generally speaking. While it would take me a while to find out the story behind the umbrella goblins, my introduction came from these two video games that I hadn’t expected to teach me much at all, much less something about Japanese culture.

I think this is probably the moment when video games stopped being just a pastime for me and instead became a way I could connect to a world that was bigger than the room where my Super NES connected to a flashing TV. Obviously, this whole site is one result of this realization, but this is especially the case for the post you’re reading now, because it’s also about the ways video games can give a person ideas about Japanese culture that are slightly odd, slightly warped and maybe altogether wrong from however they existed before someone thought to render them in pixels.

This is a story about Super Mario Bros. 3, about Mario’s raccoon tail, and about how the tanuki traveled through culture, ending up something slightly different than it was when it started.

A Japanese Tail

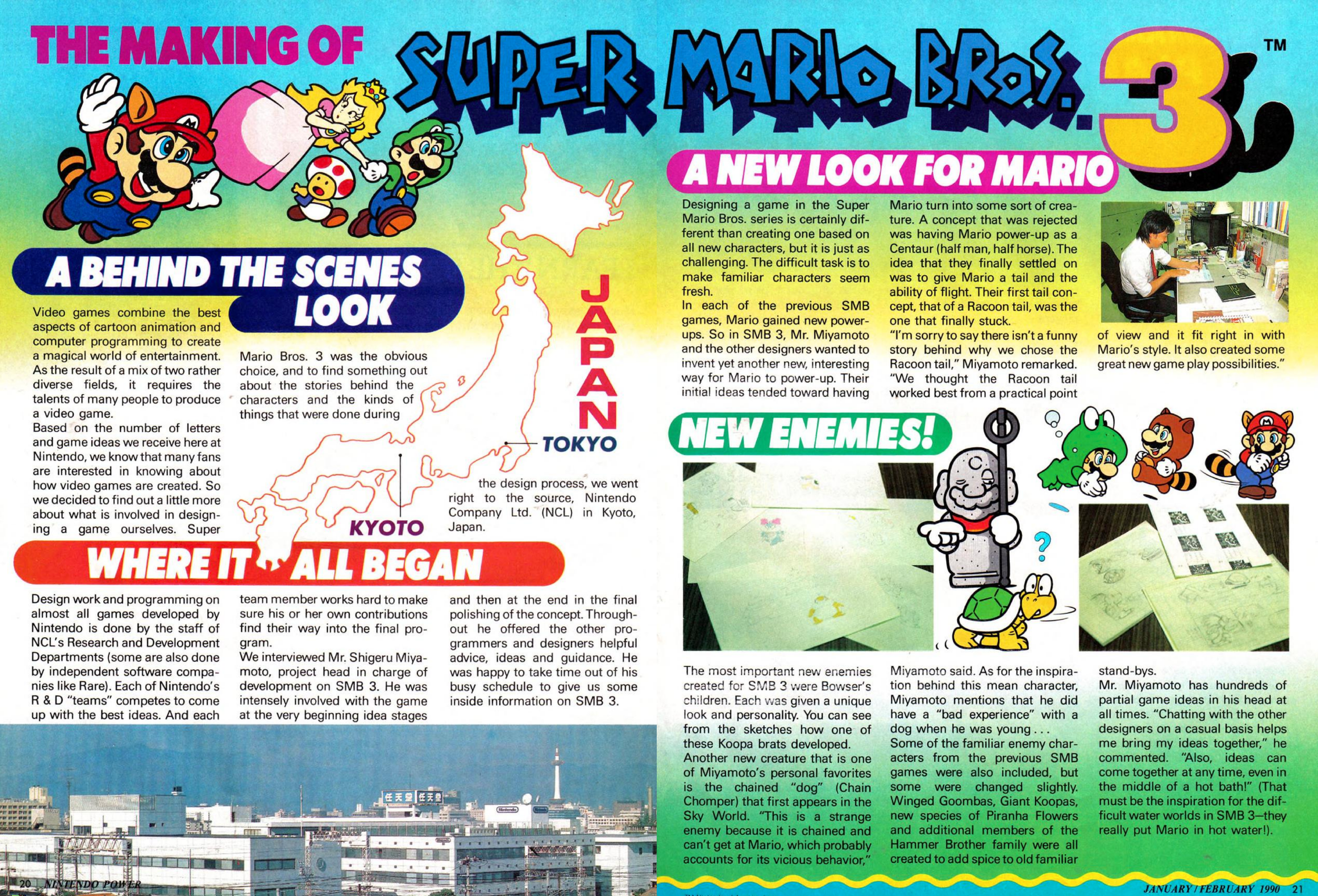

My first look at Super Mario Bros. 3 came in Nintendo Power’s tenth issue, which featured Jack Nicholson’s Joker on the cover. Between profiles on Shadowgate and Willow, the magazine ran a behind-the-scenes look at this “new” game, which had actually been on sale in Japan for more than a year. The piece forefronted SMB3’s origins in Japan in a way a lot of Nintendo coverage didn’t back in the day.

This spread also introduced me to SMB3’s new version of Mario. No longer clutching the turnip from Super Mario Bros. 2, he was now soaring high in the sky while sporting raccoon ears and a tail. The accompanying interview with Shigeru Miyamoto, who served as co-director of the game along with Takashi Tezuka, has him answering a question that would have been on a lot of would-be players’ minds: Why a raccoon? Miyamoto doesn’t give a good answer, however, explaining, “I’m sorry to say that there isn’t a funny story behind why we chose the [raccoon] tail. We thought the [raccoon] tail worked best from a practical point of view and it fit right in with Mario’s style. It also created some great new gameplay possibilities.”

That last point is indisputable. The raccoon tail truly changed the way Mario functions — and the way later sequels would innovate on the series’ hop-and-bop formula. But the process of how the development team arrived at the signature fwap-and-flap gameplay begins with a very different version of SMB3. Early on, the game was going to have a “bird’s eye view” — “looking down diagonally from overhead,” per this 2016 developer roundtable interview to promote the Nintendo Classic Mini. In the interview, Miyamoto explains that this perspective made it difficult to guide Mario in the air. Jumping being an integral part of Mario games, the perspective returned to match the more traditional side-view one seen in previous installments. (A previous version of this text described the original SMB3 perspective as “Zelda-like,” but having received some feedback on this point, I revised the text. There’s paragraph in the miscellaneous notes section explaining why.)

According to that same interview, it was during the angled-style perspective phase of game design that Mario was first given a tail.

Tezuka: A tail seems a bit forced, so I worried about that. I kept wondering if Mario and a raccoon was the right match.

Interviewer: Why a raccoon tail?

Tezuka: Because I wanted to put in a new action where players could press a button to have Mario spin around and knock enemies out of the way with his tail.

Interviewer: You originally gave him a tail so he could blow away enemies rather than fly. That’s why you chose a raccoon?

Tezuka: Yes. When we switched from a bird’s-eye view back to a side view, the controls didn’t work well and making adjustments was a challenge. Flying was something I had wanted to do since the first game, and Raccoon Mario ended up being able to do both.

Note how neither of the questions that amount to “but why a raccoon?” get straight answers. And that’s too bad. While it’s interesting how this particular power-up ended up being something Mario could use both to swipe at enemies and propel himself into the air, first one and then the other as the development process rolled along, it seems weird that it would come from an animal that does neither. Really, why a raccoon over any other animal that has a tail but doesn’t use it to attack or to fly? (Few IRL animal tails do either, I should point out.)

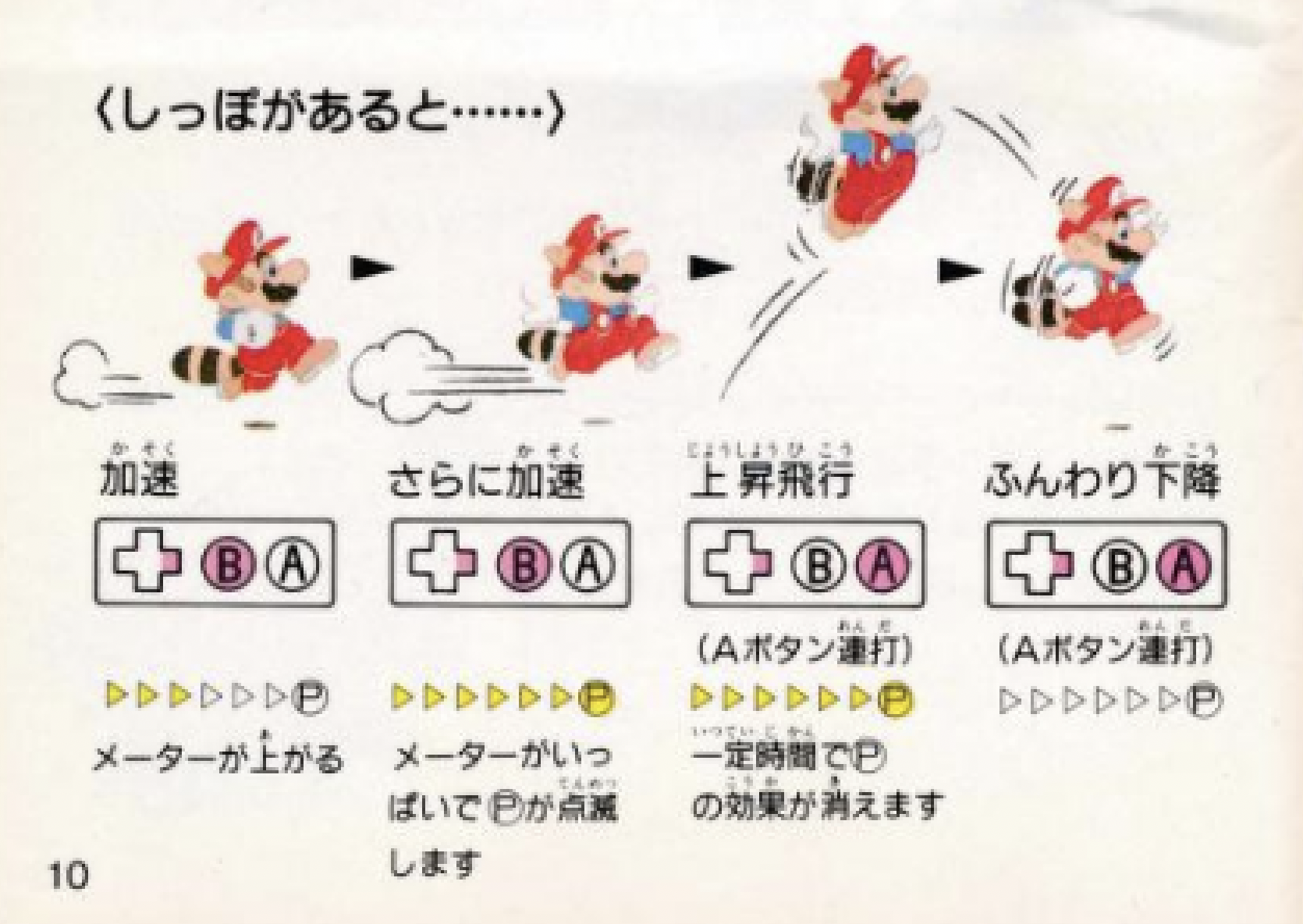

There’s no clear answer in the original, Japanese version of SMB3. In Japan, the version of Mario that appears on the box art, with the ears and the tail, is termed しっぽマリオ or Shippo Mario, literally “Tail Mario.” Take the Japanese version of the SMB3 instruction manual, for example. It refers only to Shippo Mario save for when Mario is wearing the full body “furry” version of the power-up, in which case it’s referred to as タヌキマリオ or Tanuki Mario, rendered in the English localization as Tanooki Mario. There is not a single mention of raccoons.

The header reads “And when you have a tail…” then instructs how to make Mario fly.

“Tanuki Suit / Transform into Tanuki Mario. Looks like Shippo Mario.”

“Flap flap... When playing as Shippo Mario or Tanuki Mario, you can press A to jump and then mash the A button to gently float down from midair.”

Since the tail is identical in both versions, the implication is that the tail Shippo Mario is sporting is the tanuki’s, and indeed in the Japanese version of that roundtable interview, it’s made explicit: they talk about how Shippo Mario’s tail is taken directly from the real-life Japanese canid known as the tanuki or Japanese raccoon dog (タヌキ). But again, it’s not like the raccoon dog is known for attacking with its tail or using its tail to fly.

So what’s going on here?

For one thing, the split between “ears and tail” Mario and the version where he’s wearing the full suit exists differently in Japan than it does in localized versions. In the U.S., where I first played the game, the former is Raccoon Mario, and that makes sense because raccoons are fairly mundane in this part of the world. In fact, raccoons are pretty easy to find in the entire continent of North America — from Canada down to Panama. There are relatively few instances of the Tanooki Suit item in the game, meanwhile, and therefore it made sense that this power-up would take its name from something in Japan and therefore more special than our humdrum American raccoons.

The Nintendo Power Mario Mania guide, released to promote Super Mario World about eighteen months after that first SMB3 feature, explicitly (and erroneously) stated that tanuki means “raccoon” in Japanese. (Via archive.org.)

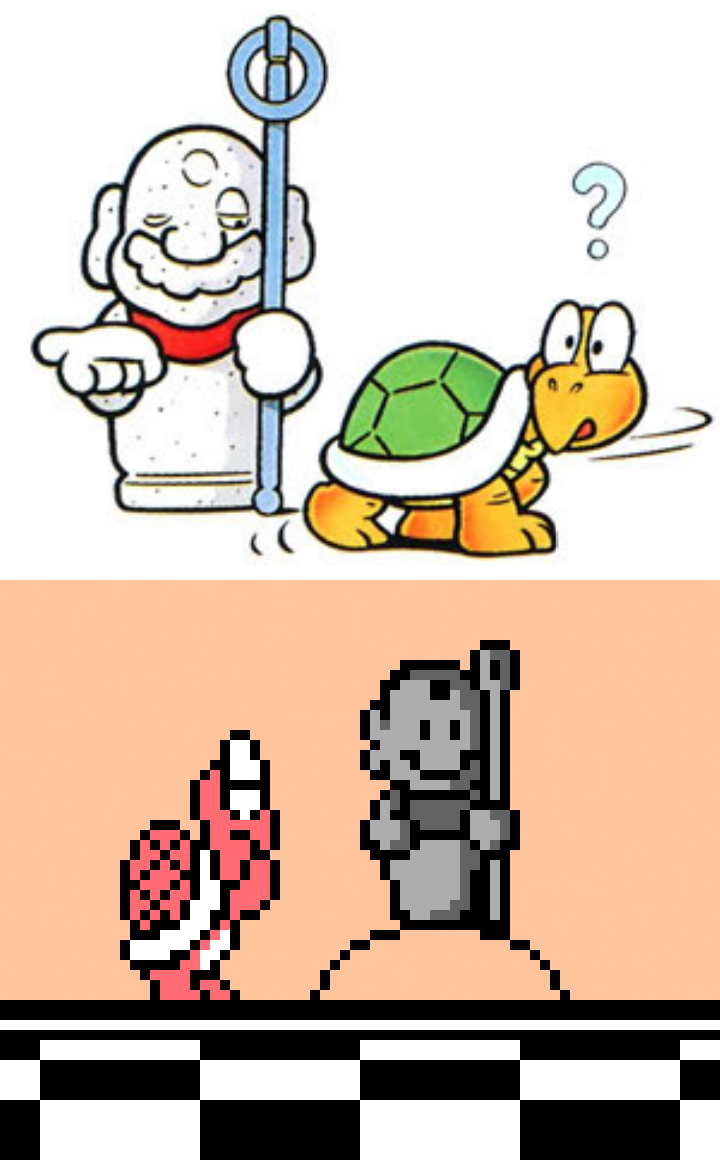

You could argue that in Japan, the split between the two power-ups mirrors the two types of tanuki: the real-life one, which for the purposes of clarity I will refer to as the raccoon dog from here on out, and the bake-danuki (化け狸), the yokai associated with this species, which I will refer to as just tanuki for the rest of this piece. In Japanese folklore, the tanuki is known as a mischievous shapeshifter, and it’s only as Tanooki Mario that players can transform into a statue, effectively granting him temporary invincibility and the ability to “fool” enemies who will walk directly past him, as if he weren’t the guy they’re trying to kill.

Top: SMB3 instruction manual showing how Statue Mario can “trick” enemies. Bottom: SMB3 ending showing the same thing, more or less

It’s also an aspect to the game that is uniquely Japanese, because to an American with no context otherwise, there’s no cultural explanation for why a raccoon should be able to turn into a statue. In fact, in the Super Mario History 1985-2010 booklet, Miyamoto is quoted as acknowledging how it could have been confusing, saying “The Tanooki Suit turns into a statue! Even though I knew it wouldn’t make sense to some non-Japanese players. … I was so excited about it that I left it in.”

I think Miyamoto took pride in inserting something explicitly Japanese into a product that was being shipped out to a worldwide audience. In fact, I think the Japanese-ness of this core gameplay concept is underscored with a specific audio cue. In the game, the standard “power-up” noise from SMB and SMB2 returns for when Mario tags a mushroom or a Fire Flower. However, there’s a unique noise for when Mario tags the leaf item that grants him the ears and tail. It’s re-used for when he grabs one of the game’s three “suit” power-ups — Tanooki, Frog, or Hammer Brother — but you hear it most often in the game from turning into Raccoon Mario, just because the leaf is extremely common in the game. This noise happens to be borrowed from Mysterious Castle Murasame, a Zelda-style Nintendo adventure released for the Famicom in 1986 but not brought outside Japan until 2014. It’s the noise of certain enemies materializing from thin air.

For a long time, I just thought Nintendo reusing this sound effect amounted to a callback to the company’s previous work, in the style of the warp whistle in SMB3 sounding like the recorder in Legend of Zelda. However, because Mysterious Castle Murasame is the most Japanese of Nintendo’s four 8-bit adventure titles — the other three being the medieval fantasy Legend of Zelda, the ancient Greece-inspired Kid Icarus and the space epic Metroid — I now consider this to be a deliberate tip of the hat to the fact that SMB3 is offering something explicitly Japanese to the player. It’s an audio cue saying something like, “Hey, here is a thing from Japanese culture,” whether the player will recognize it or not.

Even the specific power-up item that Mario must obtain to get the ears and tail ties back to Japanese folklore. It’s the Super Leaf, because tanuki have an association with both leaves and transforming. Either they place a magical leaf on their foreheads in order to change their shape or they transform leaves themselves, often passing them off as money that reverts back to the true, useless form after the fact. This connection is referenced in other games as well. To go back to Pocky & Rocky for a moment, the second character named in the franchise title is a tanuki — Manuke, in the original Japanese, though renamed Rocky the Raccoon in the English localization. Whereas Pocky (Sayo-chan, in the original Japanese), throws ofuda cards as her signature projectile attack, Rocky throws leaves. And Tom Nook, the evil lord of debt from the Animal Crossing games, is a raccoon in versions localized outside Japan. That sound-alike English name should be a tipoff, however, because in Japan, he’s a tanuki — and the way items such as furniture are represented in the player’s inventory as leaf icons recalls the tanuki’s ability to transform leaves into other objects.

So yeah, there’s a lot in SMB3 that a curious-minded player could use as a jumping-off point to learn about specific aspects of the culture that made the game, even if most non-Japanese kids playing it probably just took it all at face value. Someone could even spot a tanuki statue out in the wild and put together that Tanooki Mario’s ability to turn into a statue comes from the association this “Japanese raccoon” has with statues. (I elaborate on the statue aspect in the miscellaneous notes section.) And then, of course, there’s the flying. Surely, since it’s such an integral part of the game, tanuki in Japanese folklore must be able to fly. Right?

Actually? No. Though tanuki have many powers and can use their bodies to perform some spectacular feats, they’re not typically known as having the power of flight in Japanese folklore. A non-Japanese person who was just gleaning their basic tanuki facts from SMB3 might be forgiven for thinking that, however — and given the monumental success of the game, I’m willing to bet a lot of people probably did.

Not in the Tanuki’s Bag of Tricks

In 2003, American author Tom Robbins released Villa Incognito, a novel about 9/11, the Vietnam War and also a tanuki. The book opens with a description of the tanuki character descending from the heavens to earth using his giant scrotum like a parachute.

A tanuki using his ball sack to float downward is not exactly the same as Mario using a tanuki tail to fly upwards, but I feel it’s nonetheless notable in the pop culture canon of tanuki movement through the air. At the time I was reading Villa Incognito, I was a 21-year-old college student whose memories of playing through SMB3 were still pretty fresh. I assumed rather than Robbins being influenced directly by SMB3, it was more likely that he was drawing on some aspect of tanuki lore that was also reflected in the game.

After all, I’d seen Japanese illustrations of tanuki using that very body part in all manner of creative ways. Among the most notable of this type of illustration is the work of the nineteenth-century ukiyo-e master Utagama Kuniyoshi, who depicted tanuki using their magnificent testicle bags for everything from fishing to weightlifting to pounding mochi.

Or take a personal favorite of mine: Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s 1881 woodblock print, “Tanuki of Hiroo Plain,” in which a trio of travelers are startled by a pair of tanuki who are wielding not only umbrellas and also their massive scrotums.

Knowing how multipurpose a scrotum can be in the paws of a cunning tanuki, I assumed back in the day that the SMB3 power-up reflected things the tanuki were known to do. Surely, not only did the tanuki use these organs to swat away foes and catch wind to fly through the air, but also Nintendo was merely subbing in the tail in lieu of the scrotum in SMB3 so as not to offend non-Japanese players and their quaint notions of scrotal modesty. Japanese players, I imagined, would have been hip to what was really going on.

However, this is not the case. Debatably, a tanuki might use their scrotum as a weapon — there’s a blog post that features a Kuniyoshi print showing a tanuki whacking a catfish into submission with his — but it’s usually not wielded the way Mario does with this tail in SMB3. And nowhere in the canon of tanuki folklore was I able to find evidence of tanuki using their scrotums to fly. No, the tanuki are rather earthbound, which I suppose makes sense given how heavy those things must be to lug around.

To investigate this matter further, I reached out to some people who know Japanese folklore better than I do, and the first was Thersa Matsuura, writer and host of the podcast Uncanny Japan. Matsuura has been living in Japan for most of her adult life, and her podcast explores the origins of folklore, customs and turns of phrase she encounters there. From Matsuura’s perspective, neither the flying nor swatting aspects of the SMB3 tanuki tail figure into anything she’d encountered in Japanese folklore. “I never thought about it before, but in Japan it’s not a big deal about the tanuki’s ‘attributes,’” she said. “As far as folklore goes I have never heard of tanuki flying at all. Sometimes changing into something else (teakettle, what have you), but flying was more of a tengu kind of thing. The tail, too, I've never seen mentioned as particularly important.”

I also reached out to Michael Dylan Foster, a professor of folklore and chair of the East Asian Languages and Cultures department at UC Davis. He was recommended as someone who could attest to the presence of any of this in Japanese folklore, and he agreed with Matsuura, saying that he didn’t know of any stories alluding to flying. “The world of folklore is huge and varied, of course, so there may be legends or folktales somewhere in which a tanuki takes to the air in some fashion (or shapeshifts into a bird perhaps), but flying is not considered a common characteristic of tanuki,” Davis said. And while he pointed out that Japanese folklore features various creatures that are known for having notable tails — the kitsune, which can create fire with its tail or sometimes even its multiple tails, and the nekomata, which has a forked tail — nothing really corresponds to the SMB3 tail in any meaningful way.

Indeed, the only other example anyone I talked to could point to as an example of a tanuki flying outside of a Mario game was the Studio Ghibli film Pom Poko. Toward the end of the film, a group of tanuki attack some humans, and they enter into battle using their scrotums like parachutes.

Again, it’s not self-propelled flight like the kind featured in SMB3, but it’s something in the vicinity of that. In fact, like the tanuki descending from the sky in Villa Incognito, Pom Poko combines the tanuki-powered flight from SMB3 with the “cape-achute”-style gliding featured in Super Mario World. Whatever the case, Pom Poko opened in Japanese theaters in 1994, long after both Mario games had left their marks on pop culture, so it’s actually possible that the Pom Poko tanuki are flying through the air only because Mario did it first.

“A cape-achute… What a concept!” from the Nintendo Power Super Mario Adventures comic. (Via archive.org.)

As for Villa Incognito, I don’t know if Tom Robbins cares much for video games or if SMB3 influenced the book’s opening. His work draws on a variety of sources, from both high and low culture, so it’s not inconceivable to me that he’d incorporate an element from a popular video game. If I had to bet, however, I’d say it seems more likely that Robbins would have been inspired by Pom Poko; the dubbed version of the film didn’t make it to America until 2005, two years after Villa Incognito was released, but the subtitled version did get a limited theatrical run in the U.S. in 1995. If he watched it, it’s entirely possible that Robbins just assumed flying is part of tanuki lore and just wrote it into his take on the character.

So how likely do I think it is that SMB3 is responsible for any notion of flying tanuki? That’s tough to say. After all, with tanuki having this history of manipulating their ball sacks into all manner of helpful shapes, it doesn’t seem like too big of a stretch, so to speak, to imagine them devising a way to take to the sky. Really, it seems like a natural evolution of the tanuki’s powers, though that begs the question of why it didn’t manifest before the 1990s in stories or illustrations.

As big a deal as SMB3 was, in Japan and in the world overall, it’s hard to draw a direct line between it any notion of flying tanuki. That said, there’s at least one way this Nintendo game probably did change the way people think about tanuki — and it’s not at all regarding their scrotums.

An American Tail

Native to North America, the common raccoon is an invasive species in Japan, and by most accounts we have a popular cartoon show to thank for this fact. In January 1977, Fuji TV began airing Rascal the Raccoon (あらいぐまラスカル or Araiguma Rasukaru), an 52-episode adaptation of Sterling North’s 1963 children’s book, Rascal: A Memoir of a Better Era, about his experiences raising a pet raccoon. The show proved to be enormously successful, and despite the fact that the whole point of the narrative is that raccoons do not make good pets, the series proved so popular that fans began importing raccoons to Japan for this very reason. These pets ended up in the wild, either because raccoons are wiley and generally adept at going wherever they want or because Japanese families learned that Sterling North was not being facetious when he named his pet. Whatever the case, the population has thrived in its new home away from home, endangering native species, eating crops and destroying ancient temples and shrines in the process.

You can find limited reporting indicating that the invasive raccoon population is threatening Japan’s native lookalikes, but for the most part the International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies the latter group as a species of least concern. Hypothetically speaking, there could be ecosystems in Japan where raccoons and raccoon dogs would be competing for the same resources, I suppose. However, there is a specific niche in which the North American version is encroaching on the Japanese one — and SMB3 is certainly a symptom of the problem, if not the cause.

I’m talking about that iconic ringed tail.

In the first section of this post, I explained how English-speaking fans of the game know the “ears and tail” version of Mario as Raccoon Mario, but that terminology doesn’t exist in Japan. And in ether localization, that form is a middling form of the full “furry suit” version, known as Tanuki Mario in Japan and Tanooki Mario in English localizations. But here’s the thing: None of these forms have Mario sporting a tanuki tail. No, even in the full suit form, he’s got the ringed tail of a North American raccoon.

Raccoon dogs have a broader, more stumped tail that can shift from lighter to darker tones, ombre-style, as you move from the base and toward the tip. While tanuki share a color scheme with raccoons, they definitely don’t have the ringed tails that their North American counterparts do. So why, then, would Nintendo design Tanuki Mario with the wrong style of tail, especially if it was meant as a celebration of Japanese culture in a game intended for an international release? Why honor the lookalike invaders with the ringed tail instead of the Japanese originals?

A raccoon dog / non-yokai tanuki, sporting not a ringed tail, but a nice one nonetheless.

Left to right: Tom Nook from Animal Crossing sporting a somewhat accurate tanuki tail; “A Message From Mario” tanuki stamp from the SMB3 instruction manual, with ringed tail; and Rocky on the western box art for Pocky & Rocky, which is so Americanized that you could imagine them giving him a ringed tail, but they don’t.

For counsel on this mystery, I was referred to Brian Lee, a self-identified tanuki enthusiast who has more than once posted to Twitter to explain the differences between how these animals look versus how their North American counterparts look. According to Lee, it’s rare to find examples of tanuki with striped, raccoon-style tails that predate SMB3. They do exist, however, and perhaps the most notable one is the costume worn by Arale in the intro to the Dr. Slump anime.

The way Arale holds her hands out is even somewhat similar to how Mario poses his hands in SMB3 when he’s reached a high enough running speed to start flying, though I can’t find any record of a Nintendo staffer saying that this was a direct inspiration — not for SMB3, anyway, though Miyamoto would later say that Mario’s running animation for Super Mario 64 was modeled on Arele’s. The Dr. Slump TV show aired between 1981 and 1986, based on the manga that ran from 1980 to 1984, but Lee points to Rascal the Raccoon as the source of generalized confusion between the animals.

As far as I can tell, after the Rascal anime and the introduction of actual raccoons to Japan, raccoon imagery became more culturally pervasive. The difficulty people have telling the real animals apart slowly made its way into cartoon depictions and eventually snowballed into what happened with SMB3. I’m not sure how it is for people who grew up before the Rascal anime, but most younger Japanese people I’ve talked to have trouble telling the difference between tanuki and raccoons (real or animated). This confusion also often extends to masked palm civets/hakubishin (another invasive species with raccoon-like face markings), Japanese badgers/anaguma (face markings again), and red pandas (striped tails).

So what’s going on in SMB3, then? Were the designers suffering a case of tail blindness? Were they influenced by Dr. Slump? Could it be both?

Well, for starters, there might be something to the idea of Dr. Slump shaping the aesthetics of video games back in the day. The tanuki costume isn’t even the only element of the Dr. Slump intro to be referenced in a video game. The title screen to Sonic the Hedgehog very much seems to be referencing it as well, with Arale and Sonic posing similarly, appearing inside a ring decorated with stars and with a banner beneath. The title screen to Sonic the Hedgehog 2 makes it especially obvious, with Tails popping into the frame after Sonic, similar to how Gatachan does after Arale.

I made this gif comparison and then realized that Kaelan Ramos essentially did it already in video form, but still.

If Dr. Slump can be so culturally generative, then surely a game as popular as SMB3 could be as well. After all, Nintendo sold millions of copies of SMB3 just back in the day, not even counting ports and re-releases. It was the most popular game released on the NES/Famicom aside from the original Super Mario Bros./Duck Hunt combo that came with most purchases of the system. And while it’s since been outpaced by even bigger-selling titles, the sheer volume of SMB3 cartridges sold worldwide means that this game would have been many non-Japanese gamers’ introduction to the concept of tanuki. The fact that SMB3 had the wrong tail on Mario’s butt could have fooled many of them into thinking that’s how tanuki tails looked, much in the same way it fooled me and many other American gamers (and also maybe celebrated author Tom Robbins) into thinking that tanuki could fly.

Now, this is a blog that caters to longtime fans of video games, but I’m sure there is someone reading this who just today realized that tanuki don’t have ringed tails and don’t traditionally have the ability to fly, just because they never questioned the rules that SMB3 set for them. It could very well be that some of the people drawing ringed-tailed tanuki today are doing so because SMB3 taught them wrong, if not that SMB3 taught someone else wrong and later generations of artists just copied the ringed tail because that’s how they saw other people draw it.

According to Lee, however, the popularity of the ringed tail isn’t necessarily something we can blame on Mario, simply for the fact raccoons have one of the most stylish and most distinguished tails in the entire animal kingdom. “I do think the striped tail trend in cartoons caught on because it's a cute design element for an animated creature,” he said. “I think this combined with the general confusion between the animals has been a kind of cultural feedback loop of confusion that's been going on since the ’80s.” However, Lee also clarifies that you don’t often see raccoons drawn with tanuki tails, the likely reason being that the raccoon tails just look cuter. I suppose that point is debatable, but the fact that a Google image search for “tanuki fanart” yields a ton of erroneously ringed-tailed tanuki means that a lot of people are setting out to draw this thing and then getting one important part very wrong.

As I’ll point out in the final bit on this post, I think Lee’s point here, that raccoon tails have a specific aesthetic appeal, is an important one. It might seem obvious, but as it turns out, it actually might be the best explanation we can get for how raccoon tails got wrapped up in anything Super Mario.

A Sack Full of Conclusions

For a while there, it seemed like “ears and tail” Mario would go the way of Mario clutching a turnip, which was also iconic to the franchise until it wasn’t anymore. Although early screenshots of Super Mario World showed this powered-up form returning, it was ultimately replaced by Cape Mario, which in turn gave way to the Wing Cap Mario in Super Mario 64. We like to reinvent the way Mario flies, it seems.

The ears and tail did return in the 2003 RPG spinoff Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga, though curiously as a powered-up form of the Goomba, the Tanoomba. It’s a Goomba with the powers of a tanuki, in case the name didn’t make that clear, and it’s notable that the localized name wasn’t something like Raccoomba. This shift away from raccoons became even more apparent in 2011’s Super Mario 3D Land, where the Super Leaf is once again an item Mario can collect, but in this go-around, it transforms Mario fully into Tanooki Mario. The closest you see to the old “ears and tail” version is powered-up forms of Mario enemies that sport just the tail, no ears. They’re named as such: Tail Boo, Tail Bob-Omb, Tail Bullet Bill, Tail Goomba and in the big final fight, Tail Bowser.

Super Mario 3D Land-era Tanooki Mario is so very stoked on his culturally inaccurate tail.

In an interview with Games Radar, director Koichi Hayashida explained that dropping Raccoon Mario in favor of the full suit version ultimately came down to aesthetics.

When development had just begun on the game, we had created the ears and tail version as well as the full body suit, as well as one more that was in-between the two. We were testing all of these, asking the team members what they liked, but it seemed like they were choosing based only on visual appearance. We had to revert to a more functional mentality, deciding that the easiest one for the player to understand visually as a power-up was the full Tanooki suit.

What’s especially odd about this evolution is that as of Super Mario 3D World, Tanooki Mario can no longer fly; he can only flutter about to slow his descent to the ground. (This was apparently a result of technical limitations. Yoshiaki Koizumi, director of Super Mario 3D World, explained it away to journalists at the 2011 E3 by noting that “flying does present some interesting issues in three dimensions.”) In making this change, Nintendo inadvertently fixed its version of the tanuki to be more in line with Japanese folklore. A lot of western gamers took this as a downgrade, and an inexplicable one at that — read the comments on this Kotaku post if you don’t believe me — and I suppose for people who imprinted on SMB3 in a major way, it would seem that way. However, knowing how tanuki function outside of Mario games, I can also see how the Nintendo staff making Super Mario 3D Land wouldn’t have seen flight as an essential part of the power-up. Tanuki don’t fly, so Tanuki Mario shouldn’t have to either. (A new power-up form introduced in New Super Mario Bros. U, Flying Squirrel Mario, seems to address this.)

In that 2011 E3 press event, Takashi Tezuka follows up the explanation for why Tanooki Mario can no longer fly with another version of how the idea for Raccoon Mario/Tanooki Mario came about. He’s specifically responding to a journalist who asks how and why Nintendo made the connection between flying and raccoons in the first place — the very question Shigeru Miyamoto didn’t seem to have a good answer for twenty-one years earlier, in Nintendo Power’s tenth issue.

So actually the idea for the Tanooki suit came originally from wanting to put a tail on Mario, and so we started off by putting a tail on Mario in [SMB3]. And we wanted to use that tail so he could do the little spin move and hit enemies with his tail, as sort of an attack. But then, once we had the tail on Mario, we thought, “We’ve got this great tail. Isn’t there something else that we can do with it? So, then the next thing we started to do was to have the tail kind of flutter back and forth, and we thought that that's kind of like a propeller, so that flutter motion would make Mario a little bit lighter, so he could jump farther. But once we started doing that, it felt so good that we said, “Let’s just make him fly.”

The thing Tezuka isn’t saying, that no one from Nintendo ever seems to say outright, maybe because it seems like such an obvious thing that no one thinks it needs to be said, is that the SMB3 team picked a ringed raccoon tail because they look freaking cool. Raccoons have rad tails that are maybe *the best* animal tails, and so they went with that, even when they incorporated tanuki elements for the upgraded version down the line. Like, Davy Crockett rocked a raccoon tail, and so can Mario, just specifically on his butt and not on his head.

That might seem really reductive, but I think it’s the unifying theory of how raccoons traveled through Japanese culture and ended up intermingled with the world’s understanding of the tanuki: Raccoons are really cute.

Why did viewers of Rascal the Raccoon decide to send away for raccoons even though the whole point of the show was that they’re objectively not good pets? Well, raccoons are really cute.

Why did Akira Toriyama put Arale in an animal costume that has a raccoon tail on it? Well, raccoons are really cute.

Do we think Mario got his erroneous raccoon tail because the SMB3 team was inspired by Arale’s costume? But also Dr. Slump followed Rascal the Raccoon closely enough that we can say it’s at least probable that raccoons and their tails were big in the Japanese national consciousness? And therefore even if Dr. Slump was the direct connection, Rascal the Raccoon is the ur source of ringed tail worship in Japanese pop culture? I couldn’t find any proof, but I can for sure tell you that raccoons are really cute, and that’s enough to propel them through culture, even in a country where they don’t technically belong.

I asked Henry Gilbert about all this, and he pointed out to me that perhaps Mario has a raccoon tail in SMB3 because NES sprites are only allowed three colors. Since red is Mario’s signature color, that only leaves a dark and a light, and those happen to be the tones of a raccoon’s tail — and that’s a visual you can render in pixels fairly well, as opposed to other types of animal tails that might not read so clearly. I’m inclined to agree with him, but I think this argument is just a version of “raccoons are really cute” that makes sense in an 8-bit graphical context.

I really do think this is the explanation that various Nintendo spokespeople are never offering outright, because it’s just so obvious. SMB3 certainly helped put it in many people’s heads that this is how a tanuki can look or even should look, just in the way a lot of people will always assume that tanuki can or should fly.

You truly can learn a lot from video games, even if you’re not necessarily learning the truest, most culturally accurate version of a thing. But teach enough people the wrong thing and you just might end up changing it. I can show you a million drawings of ringed-tailed tanuki to prove this might be the case.

Miscellaneous Notes

To me, knowing that Raccoon Mario and Tanooki Mario were always wrapped up in the lore surrounding this mythical Japanese animal makes more sense of the idea that SMB3’s developers were at one point considering one of the power-up forms to be Centaur Mario. It’s actually mentioned in that original Nintendo Power spread, and apparently was rejected early on in the process, and it’s probably a manifestation of the longstanding desire to put Mario on some kind of mounted steed in a way that the NES technology could not accommodate. That always seemed like it didn’t fit along aside the Tanooki Suit and Frog Suit, but considering that the third one was the Hammer Suit, maybe it kind of does? This one gives Mario the powers of the Hammer Bros., who are not yokai but who like many Koopa enemies are yokai-like in that they are turtles with special powers in the way that tanuki are animals with special powers. Really, the Frog Suit is the odd one out because it’s the only one of the bunch that is just an ordinary frog — not that frogs aren’t great, don’t get me wrong. You have to wonder if at any point the team considered making the Frog Suit a Kappa Suit, but the Koopa-kappa connection is maybe something to be explored in a future post.

An earlier version of this post described the original, angled perspective attempted for SMB3 as “Zelda-like,” but I have since changed my wording because it was pointed out on Twitter that the angle might be more similar to games like Ninja Gaiden or Contra, where the “camera” is looking at the action from a higher perspective than you get in the NES Super Mario Bros. games. Apparently platforming games done from this angle do, in fact, make play control and jumping in particular more difficult, even if Donkey Kong Country did it more successfully on the Super NES. The specific wording that appears in the original, Japanese version of the SMB3 roundtable interview is 俯瞰 or fukan, which is often translated as “bird’s-eye view” but also sometimes as just “overlooking.” After talking with Fatimah and Anne, who help with translation and research, I decided that in this instance, “high angle” might convey a more correct sense. FWIW, any of these terms might also describe the forced perspective in the first Legend of Zelda.

Regarding the shift in perspective in SMB3 from an overhead angle to one that matched the original Super Mario Bros., the Nintendo Classic Mini interview has Takashi Tezuka pointing out that some remnants of this version of the game made it into the final product. Akinori Sao, the journalist conducting the interview points out that an example of this is the black-and-white checkered floor that appears in the game’s intro sequence and various dungeons in the game. And while Tezuka agrees that this is correct, I can’t quite see how this style of floor would make sense in a Zelda-style game, though at the very least the shift in perspective on the tile suggests a form of movement we wouldn’t get in a Mario game until Super Mario 64.

While Super Mario Bros. 3 ultimately ditched the overhead perspective, I think it did finally emerge more than twenty years later in Super Mario 3D Land, specifically in Level 5-2, which most of us probably informally think of as the “Zelda dungeon level.” It’s pretty cool, and for what it’s worth, it’s not that tough to control jumps in this perspective.

Unless I’m mistaken, this isn’t a perspective that has returned since, not even in Super Mario 3D World. Has it?

Also, knowing they wanted to do a more Zelda-style adventure where the hero had a spinning attack to repel enemies, I would imagine that they eventually realized this in Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past, where Link got exactly that. I’d never considered how this and the SMB3 tail attack might be related, but here we are.

Another interesting aspect to the Super Leaf power-up as it returned to Super Mario 3D Land is that Luigi no longer has the striped tail. In fact, he’s given a wholly different costume when he tags the Super Super Leaf: Kitsune Luigi, which gives him the same powers as Tanooki Mario but is just named after and styled after a different yokai. These versions also can’t turn into statues. That requires a different power-up: the Statue Leaf. In Japan, this item is called 地蔵このは or Jizō Konoha, “Jizō Leaf,” in reference to the type of statue you turn into. Jizō is a bodhisattva known in Hindi as Ksitigarbha and in Japan, these statues are commonplace. There’s actually a handy episode of Thersa Matsuura’s Uncanny Japan podcast explaining what these statues represent. I always thought it was interesting that the kind of statue they have Tanooki Mario change into is one that’s different from the tanuki statues you see in Japan and also here in the U.S. as well, but I suppose the point is that tanuki are tricksters who can change shape.

As if the confusion between the American raccoon and the Japanese tanuki weren’t enough, there is also the mujina (貉), which is a different yokai which also enjoys shapeshifting pranks. The same name can also refer to both the raccoon dog and the Japanese badger, a completely different animal which looks similar to the raccoon dog. In some parts of Japan, the raccoon dog may also be called a mujina, as can the masked palm civet, another completely separate species wound throughout Southeast Asia.

It’s noted in the 2009 report I mentioned earlier that raccoons have been found in each of Japan’s 47 prefectures, and although it claims introduction of the species began in the 1960s, well before the Rascal the Raccoon cartoon began airing. The explanation might be raccoons escaping zoos, but literature about the raccoon problem in Japan, however, almost always squarely talks about Rascal specifically being the problem. I suppose raccoons would not have reached critical mass there without the show.

The Japanese name for the raccoon is araiguma (アライグマ), literally meaning “washing bear,” as a result of the species tendency to dunk its food in water. It’s actually not clear why they do this, though scientists have had various theories over the years. The scientific name for the species is Procyon lotor, the genus name meaning “before the dog” and the species name literally meaning “laundryman.”

In 1969, Disney produced a live-action adaptation of Sterling North’s book, simply titled Rascal and starring Billy Mumy from Lost in Space. I actually saw this movie when I was a kid, and it took until writing this post to realize that it was the same raccoon story that spawned the anime. Pop culture is super weird.

The opening theme for the Rascal anime is “To Rock River.” It’s very catchy, and if it sounds familiar to you even if you haven’t seen the show, it’s apparently because it’s also apparently the BGM for the arcade version of the 1981 video game Frogger.

Rascal also stars in his own video games. For example, in 1994, the puzzle title Rascal Raccoon was released for the Super NES, where you can play as either Rascal or Sterling North, who died in 1974 and who is probably one of the least likely humans to be playable in a video game. The game was developed by Masaya, which also did various Battletoads games, the Cho Aniki games, the Der Langrisser games and the fighting game Ranma ½: Hard Battle.

There is one connection I could find between Rascal the Raccoon and the Mario games, and that’s Yōichi Kotabe, the longtime Nintendo illustrator who is credited with defining the look of the Mario characters — specifically taking the box art for the original Super Mario Bros, which features a mostly accurate Mario, a blue ox-looking Bowser and a more juvenile-looking Peach, and distilling them down to how they more or less look today, especially with the green, more turtle-looking Bowser and the taller Peach. Kotabe was also an animator on Rascal the Raccoon. Alas, he did not contribute designs to SMB3, so there’s no chance he’s the one who snuck a raccoon tail onto Tanooki Mario.

In putting this post together, I realized I wasn’t sure what was going on with the female version of the Tanooki Suit as seen in Super Mario 3D World, when Peach and Rosalina can use it. So I asked on Twitter, and apparently my guess that the lower part of the costume is some variation on a bubble skirt was way off. Most respondents guessed that it was either bloomers or pantaloons, but I have to be honest and say that my fashion vocabulary was almost exclusively informed by Project Runway and this is a matter that series didn’t tackle.

So what article of clothing would you liken that ladies’ Tanooki bottom to?

At the very top of this article, I mentioned Pumpkin Zone, the Halloween-themed world in Super Mario Land 2. Since I probably will not mention it again, I will take this opportunity to point out that another of the baddies you find in this area is J-son, as he’s called in the original Japanese version. He’s an homage to Jason Voorhees from the Friday the 13th movies. Functionally, the enemy is identical to a Goomba, but the aesthetic is a reference to a kind of movie that I am surprised a Mario game would acknowledge… though I suppose that’s not the strangest pop culture connection you can make with Super Mario Land 2.

That’s a knife sticking out of the top of the hockey mask, in case the pixels don’t make it clear.

Please check out the Uncanny Japan podcast, BTW. Matsuura does a great job finding lesser-known bits about Japanese culture and she really revels in the weird and creepy. Her round-ups of Japanese superstitions are particularly good, and this episode about the creepy children’s song “Kagome Kagome” was great. You can’t go wrong with toilet gods, either. And there are two different episodes about tanuki. Enjoy! And do support her on Patreon if you’re into her whole vibe.

Finally (at long last), I do actually have my own creepy raccoon story. It really happened. It’s both horrifying and gross and will not make you want a pet raccoon. It’s called “She Everywhere,” and you can read it here.