Why Is Super Mario Bros. 2 Missing a Level?

As a kid, I loved Super Mario Bros. 2 because it was weird. But I always wondered why it offered less overall than the original Super Mario Bros., at least as far as level structure goes. While Super Mario Bros. boasts a tidy thirty-two stages — four apportioned out over eight themed worlds — Super Mario Bros. 2 only offers twenty: three per themed world, with the seventh world randomly only offering two. That last word is Wart’s fortress in the clouds, and those levels are longer and harder than you find in the rest of the game, but it still felt like the game was shortchanging us, even back then.

The first world has three levels.

The desert world has three.

The ice world has three.

But the last world just has the two, and there’s nothing in Super Mario Bros. 2 to explain this.

Of course, the game we westerners call Super Mario Bros. 2 is a modified version of what was released in Japan as Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic (夢工場 ドキドキパニック, “Dream Factory: Heart-Pounding Panic”). The cast of characters created for that game was replaced with characters who would be familiar to Americans who played the first Super Mario Bros., but it wasn’t exactly a one-for-one substitution. Whole characters not vital to gameplay got cut, and with them went the explanation for why there is no stage 7-3.

The answer lies in the backstory for the game. If you open the Doki Doki Panic instruction manual, you’re told of a storybook describing the land of Mū, where the kind of dreams people have at night determine what the weather will be the following day. In order to ensure only good weather, the residents of Mū build a machine that makes for only good dreams. However, a villain named Mamū seized control of the dream machine and used it to make monsters. Only when the residents of Mū learned Mamū’s secret weakness — vegetables, for some reason — do they send him back where he came from.

The book containing this story, the instruction booklet continues, finds its way into the hands of two twins, Poki and Piki, the younger siblings to the game’s main character and Mario analogue, Imajin. When the twins fight over who gets to hold the book, the last page of this story is torn out, and in a rather meta twist, the removal of that page means that Mamū was never defeated. His hand emerges from the book and pulls the twins in — again, for some reason — and a pet monkey named Rūsa alerts Imajin, his parents and his girlfriend, and they all collectively also jump into the book to save the kids. The adventure of Doki Doki Panic revolves around the player essentially rewriting that final page of the story.

Translation: The Strange, Strange Story of the Dream Factory / Awakening in the dreamland, Mūkai.

This is a tale about a place far away that no one really knows. In the dreamland of Mū, many people live happily. It's a strange land where the dreams of the residents dictate the weather. With good, happy dreams comes fine weather, while bad dreams bring storms. But, who knows what kind of dream will come until the day of. And so, the people of Mū invented the Dream Machine to create plenty of good dreams.

However, one day the mischievous monster Mamū tampers with the machine and all hell breaks loose! Instead of dreams, loads of monsters appear, wreaking havoc. Mamū relishes in everyone's distress. To scare him off, they go to the Dream Machine with something he hates: vegetables. Mamū was crushed by all the vegetables and surrendered. And they all lived happily ever after.

Translation: Piki and Poki and the giant hand that appeared out of nowhere!

This is a tale about when Rūsa the monkey brought an old picture book from somewhere. Twins Piki and Poki were absorbed in the story as they read. But eventually, they started fighting over the book and tore up the last page that said Mamū had surrendered. At that moment, in a flash of light, a large hand appeared and took them both away into the storybook! Imajin and his companions hear their screams and see Mamū running through the picture book with Piki and Poki in his arms. Imajin immediately reached out his hand, and he, along with his father and the others who looked on with surprise, are pulled into the book. Your goal: the Dream Factory, where Mamū resides. Work together to save Piki and Poki!

A version of this story plays out in the game’s intro sequence, which manages to capture the gist of it. Even then, however, if you didn’t have access to the instruction booklet, you wouldn’t know about the part where the twins accidentally tear out the final page of the story and you might be still be surprised when you get to level 7-2 and find out it’s the last one.

As a result of this setup, Doki Doki Panic has a slightly different ending. In Super Mario Bros. 2, defeating Wart causes a doorway to open, and that doorway takes your character to a room with a vase plugged with a block. Once the block is removed, the captive Subcon fairies spring out. In Doki Doki Panic, however, defeating Mamū just leads directly to the scene where the celebrating fairies haul away his corpse; instead of standing on a pedestal, the heroes are standing on top of a cage holding Poki and Piki, which unlocks, and then the whole family emerges from the book.

Again, there’s nothing in-game that would explain why there is no level 7-3. I wonder if perhaps this is just how the game was designed — if maybe technical limitations meant there could only be twenty levels, and then the framing story was written to explain away the missing level. Whatever the case, the nature of the world these characters exist in was never elaborated upon, because Imajin and his family never appeared in a subsequent video game. Unlike the enemy characters, who showed up in Super Mario Bros. 2, they were all swapped out for existing Mario characters.

Given Nintendo’s throbbing love for its own history and the rampant nostalgia mining it does in the Smash Bros. series, it might seem odd that Imajin and his family has not even got a cameo. The explanation for this lies in Communications Carnival Dream Factory ’87 (コミュニケーションカーニバル 夢工場'87), a sort of World’s Fair-like event held in Tokyo and Osaka to celebrate technology, imagination and achievement. The event was sponsored by Fuji TV, a Japanese television station, and was to some degree inspired by a trip to Carnival festivities in Brazil — which, given my theory about the origin of the Street Fighter II character Blanka, makes me want to know more about the relationship Japan had with Brazil and Brazilian culture during this time period. Imajin and his family served as mascots for the event and were created for marketing purposes by Fuji TV, not Nintendo.

All further information I have about Dream Factory ’87 comes from the below GTV Japan video on the event, which cites a book titled Yume Kōjō Complete Chronicle (夢工場全記録) as the main source of its information. As I do not have access to this book, I’m relying on this video reporting the information correctly. It’s a great informational download, especially if you’ve had it in your head that Doki Doki Panic was created for some sort of Japanese event without ever being told what the nature of the event was.

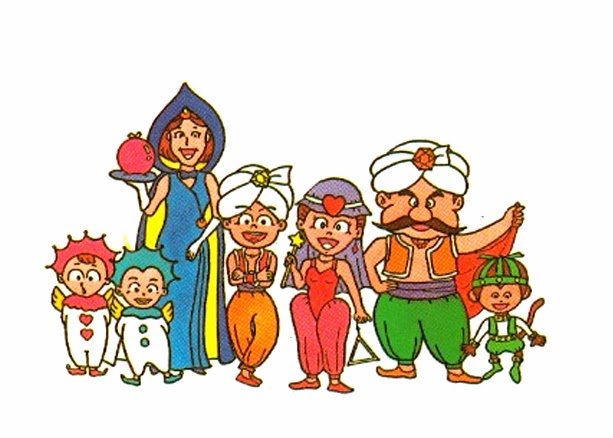

So why did Fuji TV choose this family to be the mascots for a Carnival-inspired event held in Japan and themed with Italian-style masks? The best answer I can offer is that Dream Factory ’87, as a result of this collision of elements taken from different world cultures, was international in a way that makes me think of Disney World’s Epcot Center; therefore, bringing in another culture in the form of this mascot family furthered this goal, even if Imajin and his family don’t represent a specific nation. I think if you asked the design team at the time, they would say these characters were meant to evoke Arabian fantasy lore such as Aladdin and One Thousand and One Nights — and, by extension, the part of the world where these stories come from. Personally, I don’t know if they deserve points for inclusivity, just because Imajin and his family also amount to a broad stereotype of how people from other parts of the world might imagine people from this region dress. (I expand on this point in the notes section at the end of the piece.)

Considering that Epcot opened in 1982 and that it’s also a celebration of technology, imagination and international culture, I would say that Dream Factory ’87 owes a good chunk of inspiration to Epcot. Notably, one of the signature rides at Epcot since the day the park opened is The Journey into Imagination (now just called Imagination), where its mascot, Figment, sings a song about… imagination, wherein the word “imagination” is said repeatedly. The fact that Fuji named its main mascot character Imajin (イマジン), from the Japanese rendering of the English word “imagine,” makes it seem like a direct nod, but I suppose Disney does not technically own the concept of imagination, though the GTV Japan video notes that the people who created the experience of this event were called “imagineers” — a term that is a registered trademark of Disney Enterprises, Inc. While the company has used it to describe the people who create attractions for its theme parks going back to the earliest promotions for Disneyland back in 1955, Disney didn’t trademark “imagineer” until 1990 — notably just three years after Dream Factory ’87 used it.

The GTV video also points to the central theme song of Dream Factory ’87 as being a further tie-in to Imajin’s family. That song is called “Arabian Nights,” though there’s not much about that name that’s reflected in the actual sound nor is there any trace of it in the music composed for Doki Doki Panic. (The band playing the theme went by the name Yume Kojo and later changed it to The Blimp Club, as a nod to the iconic blimp that flew over the event and which also appears in the title screen to Doki Doki Panic. The band is still active today.)

Even playing through Super Mario Bros. 2, it’s clear how the game was meant to evoke Arabian fantasy. The pipes of the original Super Mario Bros. are replaced with ornate vases that may or may not have snakes jumping out of them. The Pidgit enemies ride magic carpets that the player can steal and ride on their own. And the game’s underground music suggests something that’s… vaguely Middle Eastern, if only broadly, in the way that much of Street Fighter II’s “world music” is inspired by a stereotype of a foreign culture rather than anything outright representative.

The process of turning Doki Doki Panic into a Mario game resulted in the elimination of two more touches of the Arabian theme, both related to the Subspace gameplay element. In Super Mario Bros. 2, players enter this area by throwing a potion on the ground and creating a magical door. In Doki Doki Panic, however, the item that serves this purpose is not a potion but the kind of traditional oil lamps we associate with the genie in the story of Aladdin. It’s an interesting substitution, since potions had no role in Mario canon before or after, so it really does seem like an effort on the localization team’s part to pull the game away from the Arabian setting and bring it closer to Super Mario Bros.

The other element that got cut in the transition to Super Mario Bros. 2 was the music that plays in the Subspace area, which in the wester version is a remixed version of the Super Mario Bros. overworld theme. In Doki Doki Panic, however, it’s something clearly meant to evoke some version of Middle Eastern culture.

Because the title includes the year in it, I always had assumed that Dream Factory ’87 was just 1987’s installment of an event that occurred yearly in Japan. It wasn’t. It was a one-off event, and as a result, Imajin and his family didn’t get a repeat performance outside as festival mascots or as video game heroes. Ultimately, Nintendo wrote them out of history twice: once when Doki Doki Panic became Super Mario Bros. 2 and again when the western Super Mario Bros. 2 was sent back to Japan as Super Mario USA, effectively telling Japanese players that this was a Mario game now and that Imajin never happened, more or less.

As I mentioned in my Super Mario Bros. 2 piece, the Doki Doki Panic heroes’ legacies live on the abilities Mario, Luigi, Peach and Toad have in later games, for the most part. Mario inherited Imajin’s all-roundedness, Luigi got Mama’s high jumps (though technically he was getting that anyway in the Japanese Super Mario Bros. 2), and Peach got Lina’s ability to hover in mid-air. Toad sometimes is given Papa’s ability power to lift heavy things more easily than his small frame should allow, but not always.

Everything else is gone for good, including Piki and Poki and Rūsa, who don’t have counterparts in Super Mario Bros. 2, and with them went the backstory, the storybook framing narrative and the explanation for that final missing level.

In the end, the real level 7-3 was the friends we made along the way.

Miscellaneous Notes

Throughout this piece, I didn’t refer to Imajin’s family as Arab or Middle Eastern. The former wouldn’t be accurate, and the latter is problematic for a few reasons — among them, the fact that it’s not always clear how many countries beyond the Arabian peninsula are included in the Middle East and the fact that this region doesn’t have a single, unified culture any more than, say, Europe, Asia or Africa do. As it turns out, Fatimah, one of the two translators I work with on this project, happens to be a Kuwaiti/Irani living in Japan, which gives her a unique perspective on this intersection of cultures. When I asked her how to describe Imajin, she dubbed him, “a stereotypical mash-up of West Asia, South Asia, and North Africa that has been coined the ‘Middle Eastern look’ despite some of these regions not falling under the definition of the Middle East.” She also underscored the importance of Imajin and family being a “brown stereotype” — in her words, “Middle Eastern-seeming, whatever that means, but not actually.” And I’m inclined to agree with Fatimah.

GTV Japan has a follow-up video explaining the business relationship between Nintendo and Fuji TV, which includes the production of All Night Nippon Super Mario Bros. and which explains how the Super Mario theme song eventually got lyrics, if not completely official ones.

Another connection between Dream Factory ’87 and Super Mario Bros. 2 is the masks, which were a central visual theme for the festival. That’s why nearly all of the enemies in associated video game also wear masks — or just are masks, in the case of Phanto and the final boss before Wart. Along with the missing level, this was one of the lingering questions I had about Super Mario Bros. 2 back in the day: What’s with all the masks? I never knew until I found saw the below clip advertising the event, and then it all finally came together.

Just as translating Doki Doki Panic to Super Mario Bros. 2 meant scaling back the extent of the Arabian fantasy theme, it also meant reducing the masks as a visual theme. Stackable, chuckable blocks that in Super Mario Bros. 2 are shaped like mushrooms are, in the original game, colorful masks like the kind seen in the video.

You can see some similarity in the Doki Doki Panic masks and ones in this image, from a promotional booklet for the event. Also my god, these masks are more horrifying than Phanto.

It is wild to me that the people who designed Doki Doki Panic knew that Imajin’s family had a pet monkey with a propeller hat that could conceivably make him fly and then didn’t make this part of the game at all. “Hey, kids! Would you rather you could play as this guy’s mom and dad? Or his magic flying monkey?” The monkey’s name, Rūsa, is a play on the Japanese word for “monkey,” 猿 or saru.

There is one connection between Doki Doki Panic and Mario that actually predates the decision to turn the game into the western Super Mario Bros. 2. On page 37 of the instruction booklet, there appears a phone card featuring Mario, Peach, Lina and Imajin together.

Translation, for what it’s worth, even though it doesn’t explain the image on the card: Telephone Card Present / Thank you for purchasing Dream Factory: Heart-Pounding Panic. To commemorate the release, Fuji Television Network will present 2,000 winners with commemorative telephone cards (limited edition, not for sale). Please read the following application guidelines carefully before applying.

How to apply: Peel off the application sticker at the beginning of this book, put it on a postcard with your postal code, address, name, and phone number.

Mailing Address: Applications should be sent to "Dream Factory: Heart-Pounding Panic" section, Fuji Television Business Bureau, Ushigome, Tokyo 162-91, Japan.

The deadline for the first drawing is July 31 (postmarked by July 31), and the deadline for the final drawing is September 9 (postmarked by September 9). Winners will be announced by mail.

“There will be 1,500 winners of the initial drawing and 500 winners in the final drawing.”

I think the phone card just represents corporate synergy between Nintendo and Fuji TV. It is just a coincidence that these four characters would be further linked down the road, when Nintendo decided to make Doki Doki Panic into a Mario game.

A preliminary version of Super Mario Bros. 2 featured a different underground theme — a very cool, very beatbox-y remix of the underground music from the first Super Mario Bros. I hadn’t heard this until doing the research fort this piece.

For what it’s worth, the version of the underground theme that made the final cut of Super Mario Bros. 2 is slightly different from what plays in Doki Doki Panic.

One way that Nintendo did acknowledge the existence of Doki Doki Panic — that is, as a thing separate from Super Mario Bros. 2 / Super Mario USA — is in the lyrics to Birdo’s song in Paper Mario: Color Splash, which namecheck the original game and the fact that that is ultimately where Birdo got her start.

If you want to read more about Doki Doki Panic, check out these other posts: