The Enemies of Super Mario Bros. 2

In the first post, I tried to document where and how the various elements introduced in Super Mario Bros. 2 have persisted in later Mario games. I got to just about everything other than the enemies, which will probably end up being the game’s most notable legacy — or at least the longest chunk of this project I have for some reason embarked upon.

So here they are, in order of when each made their second appearance after SMB2.

By far, the Super Mario Bros. 2 character who has most successfully integrated into the Mario series is the Bob-Omb, the walking explosive device who is the only one of all introduced in SMB2 to also appear in Super Mario Bros. 3. Ever since, Bob-Ombs have appeared in virtually every Mario game and spinoff, and if you can think of one that does not feature them, do let me know.

Left to right: SMB2, the All-Stars version of SMB3, Mario Kart Tour, one of the only Mario enemies depicted accurately in the Super Mario Bros. movie.

The character has changed minimally since SMB2. In its original incarnation, the Bob-Omb has arms in addition to feet; later versions of the Bob-Omb would have no arms and often with a little wind-up key in back. That is about it.

I have always thought of the English name as a nod to Bullet Bills in the original Super Mario Bros., and that name has remained unchanged in English-speaking territories. That’s not the case in Japan, to the point that it’s slightly less clear that this is, in fact, the same character. In Super Mario USA, the Japanese translation of the western SMB2, the character is named ボブ — Bobu, or “Bob.” The Japanese version of SMB3, however, calls the character ボム兵 — Bomuhei, or “bomb” + hei, “soldier.” The Japanese SMB3 instruction manual seems to be hinting that name change notwithstanding, this walking bomb enemy is, in fact, the same character from Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic, saying, “Its walking looks cute, but be very careful when it flashes. It even blows away [its] companions. Take a good look and you might notice you've seen it somewhere.”

From the Japanese instruction manual for Super Mario Bros. 3.

The fact that SMB3 came out in Japan on October 23, 1988, and SMB2 came out in the U.S. on October 9, 1988, means that Nintendo had decided to re-use Bob-Omb, then a Doki Doki Panic character, long before he became a Mario character with the release of the American sequel.

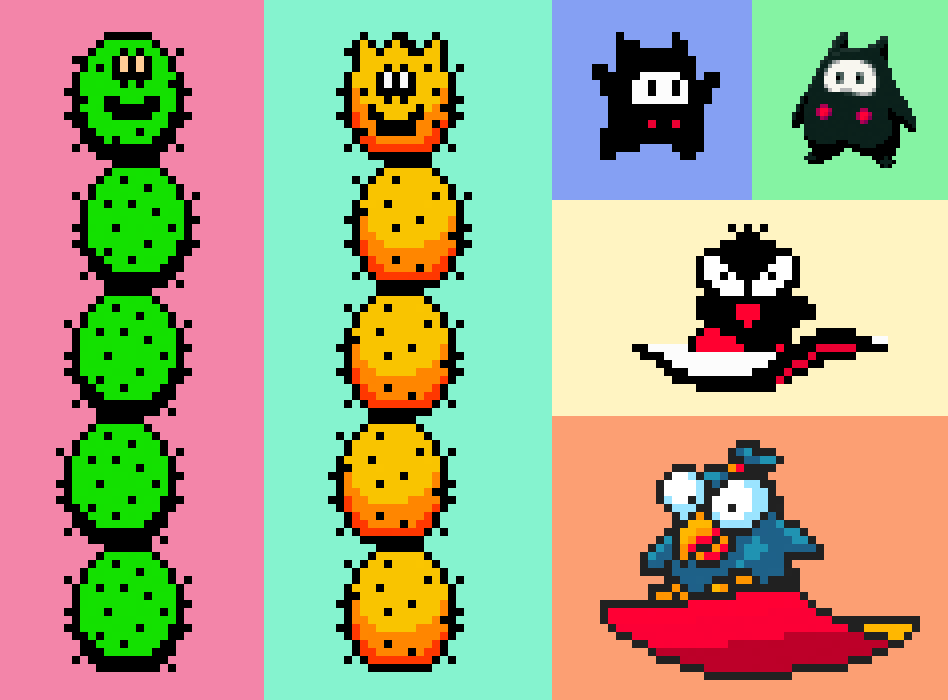

Coming in a close second behind Bob-Omb is Pokey, the grotesque ambling cactus whose torso becomes a new head when you tear off his head. Horrifying, really. While taking a break from SMB3, Pokey reappears in slightly modified form in Super Mario World. Some form of Pokey has appeared in nearly every subsequent Mario game. In Doki Doki Panic and in every Mario game, the character’s Japanese name is サンボ— Sanbo, from サボテン — saboten, “cactus.”

Pokey is not the only refugee in Super Mario World, however; one of the rarest enemies in that game is the Ninji, which originated in Super Mario Bros. 2 and which have only somewhat recently become popular recurring Mario characters despite being long-lived in the series. The Ninji are black little impish things that either hop in place or give chase to Mario. In Super Mario World, they’re called Mini-Ninjas, and this may be a nod to an explanation of their original Japanese name put forth on the Super Mario Wiki: ハックン — Hakkun, which might be derived from the name of the real-life ninja Hattori Hanzo + the honorific suffix kun. They appear in Super Mario World’s final level, Bowser’s Castle. I have no idea why Nintendo would rescue them from obscurity only to use them in such a limited way, but there they are.

Clockwise from the top-left: SMB2, SMBW, SMB2, Mario & Luigi: Paper Jam, SMB2, Super Mario All-Stars.

In the artwork in the SMB2 instruction manual, they looked like fanged critters, but Nintendo has since cutesied them up into plush little ninja-type critters with buttons sewn onto their chests. That’s how they looked in the Paper Mario games, which was only one of subfranchises of the Mario series to do much with the Ninji for years. They appeared in Super Mario Run and maybe more notably in Super Mario Maker 2, where they represent the “ghosts” of other players’ runs through levels. I’m guessing that level of visibility is what earned the Ninji its first playable spot in a Mario game just recently — in Mario Golf: Super Rush. You’ve come a long way, Ninji.

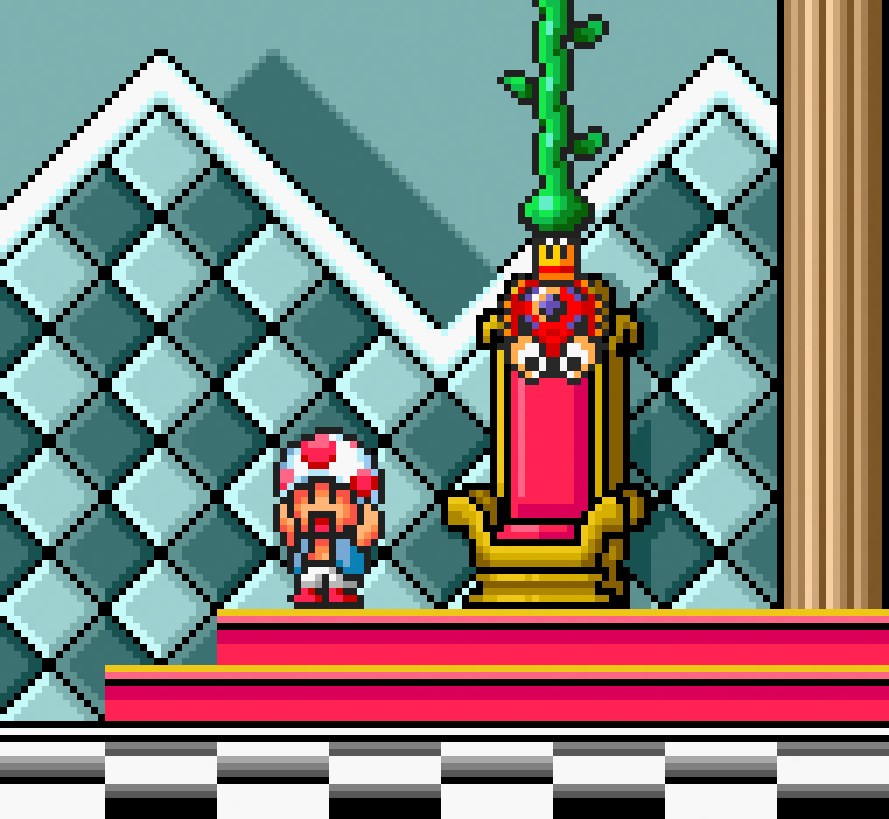

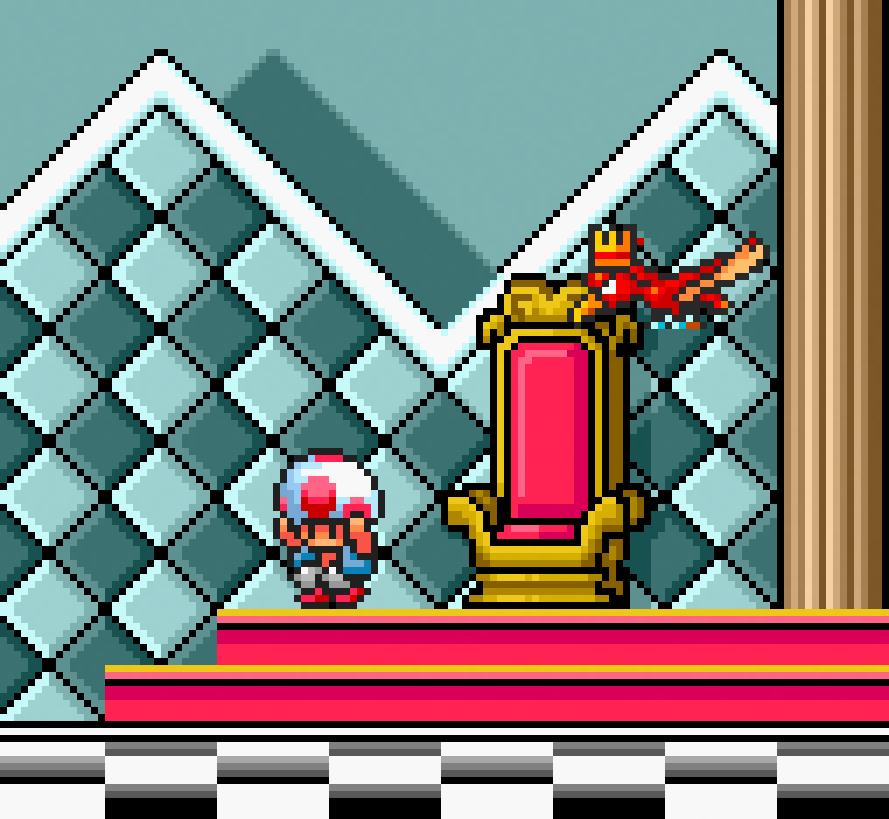

There is actually one more SMB2 holdout who makes the smallest of appearances in Super Mario World: Pidgit. In SMB2, Pidgit is the bird enemy you must throw to a grisly death in order to hijack his magic carpet. For whatever reason, Pidgit returns in Super Mario World only after you beat Special World, triggering the change in seasons/color palettes and causing some enemies to have modified sprites — Piranha Plants become Pumpkin Plants, Koopa Troopas now wear Mario masks and Bullet Bills get turned into Pidgit Bills. They all function identically to their regular counterparts, so the Bullet Bill cannons are now just firing out these black birds, which is weird for a few reasons, but especially because Pidgits never really got a major shout out like that again in another mainline platformer game, appearing only in Wario’s Woods, Mario & Wario, Mario & Luigi: Partners In Time and the ending of Super Princess Peach.

Pidgit’s Japanese name is a real whopper: ドドリゲス, or Dodorigesu — which Super Mario Wiki claims is a portmanteau of the names of two extinct flightless birds: the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire, which I had never heard of before now. Not a reference I was expecting in a Mario game, but hey — the little guy’s most prominent characteristic is being a bird that can’t fly on its own. But it may also be connected to ゲス — gesu, “crude, boorish,” and the related ゲスい — gesui, “sleazy; vulgar; low-life; shabby.”

In 1993, Nintendo remade Super Mario Bros. 2 along with the other NES Mario games for the Super NES as Super Mario All-Stars, and in doing so managed to sneak extra appearances for three generic enemies who otherwise only exist in SMB2: Cobrat the snake, Hoopster the ladybug and Albatoss the albatross, each of whom appear in the remade SMB2 but also in a new context as transformed Mushroom Kings in the remade Super Mario Bros. 3. In the original NES version, those kings have been turned into a dog, a spider and a vulture, respectively. Beyond these brief appearances, Cobrat doesn’t appear again in a significant way ever again — and Hoopster and Albatoss at all.

Since I’ve been sharing the explanations for the Japanese names of these characters so far, I might as well point out that in Japan Cobrat is ガラゲーロ — Garagēro, presumably from the Japanese word for rattlesnake, garagara hebi, and also ゲロ, “spew.” (Don’t google that, BTW.) Hoopster is, perplexingly, ターペン — Tāpen, apparently “turpentine,” — although the only reason I can imagine why is that turpentine comes from a tree resin that attracts beetles. Ladybugs are beetles and in SMB2, Hoopsters are almost always depicted as clinging to vines and trees. Albatross, whose job it is to drop Bob-Ombs on our heroes, is more sensibly トンドル — Tondoru, probably a portmanteau of トス (tosu, “toss”) and コンドル (kondoru, “condor,” which would mean the American name is actually a fairly good translation of that pun. But it could also come from 飛んでいる — tondeiru, “to be flying or jumping.”

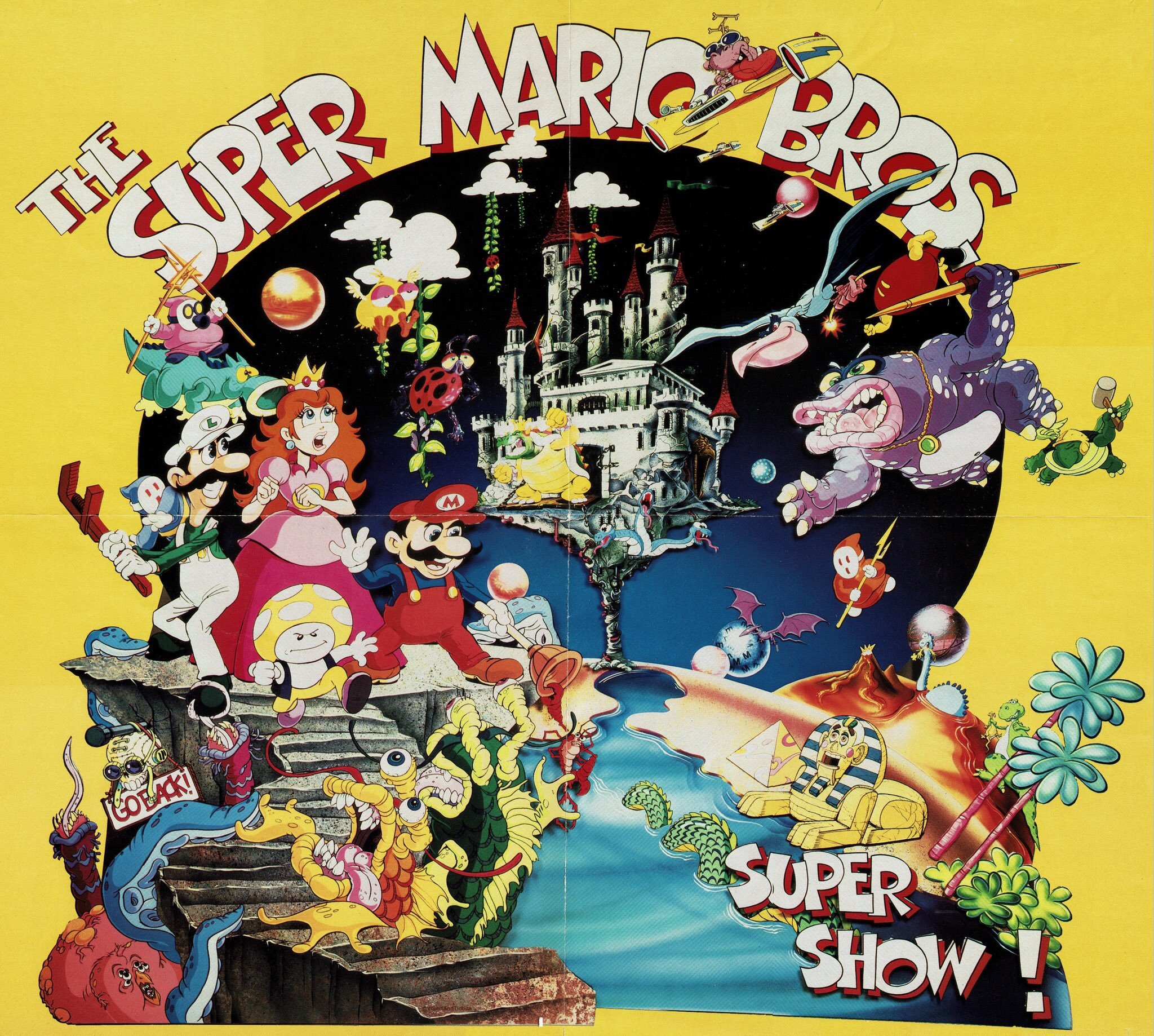

Birdo is a recurring Super Mario Bros. 2 boss who’s probably crossed over the biggest of any characters introduced in this game — not as consistently as Bob-Ombs but to a higher status, at least; today, she’s regularly playable in most Mario spinoff titles, though it took a hot second for her to make the cut. Technically speaking, Birdo also gets an extra appearance in Super Mario All-Stars — on the title screen in a 16-bit style for the first time, and she even actually appears on the game’s box art.

Left to right: SMB2, Super Mario Advance, Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga, Super Mario RPG.

Following All-Stars, Birdo’s second appearance was in Wario’s Woods in 1994, which, considering that Wario had yet to hit the big time, served as a collection of B-level Mario characters. The code for the 1995 Virtual Boy title Mario’s Tennis features the name CASSARIN, which is presumably a reference to Birdo’s Japanese name, キャサリン — Kyasarin or Catherine. The implication is that she was perhaps at some point intended as a playable character. It makes sense that someone is missing, because the game’s roster has only seven characters, and Birdo would have rounded it out to eight. Birdo finally became playable in the Nintendo 64 version Mario Tennis, released in 2000.

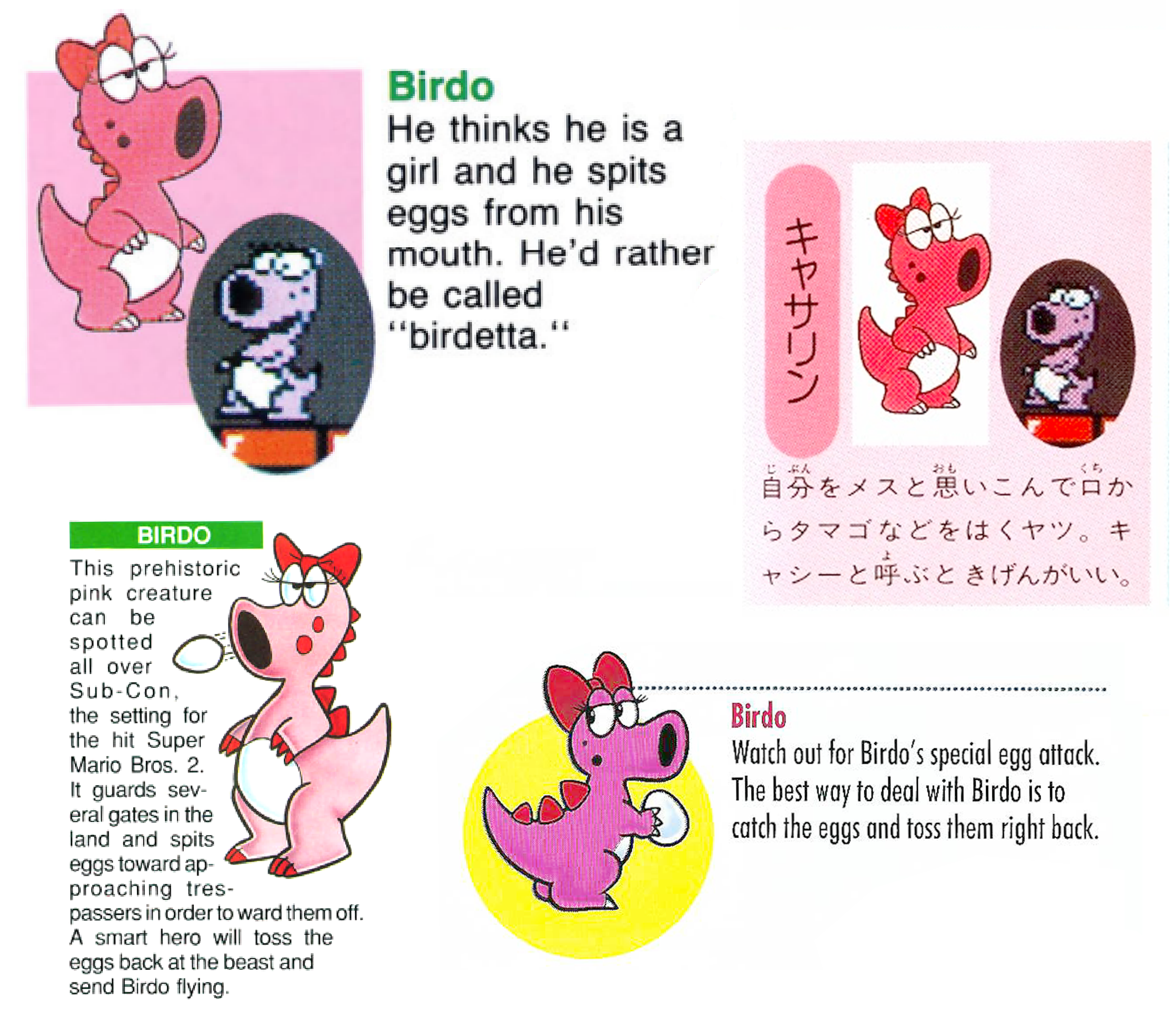

The subject of Birdo’s gender is probably something that should be its own article at some point in the future, because there is a lot to be said about what words Nintendo has chosen to use in describing this character over the years. But since I’m talking about characters and concepts introduced in Doki Doki Panic/Super Mario Bros. 2 that have permeated through later Mario games, I’ll at least point out that the discussion of Birdo’s gender actually began in Doki Doki Panic.

The English instruction manual for SMB2 famously describes Birdo as a male character who “thinks he’s a girl” and would “rather be called Birdetta,” but this just parallels how the character is described in the Doki Doki Panic manual, where she’s called Catherine but it’s also explained that she likes to be called Cathy — or sometimes Cassie, depending on the translation for the same reason that Final Fantasy VII’s flower merchant heroine is sometimes Aerith and sometimes Aeris. For whatever reason, the people who localized SMB2 decided to keep the idea that Birdo has a given name and a preferred name, but they also chose a new pair of names that accentuated her gender. Catherine and Cassie are traditionally feminine names, but the English version gave her a name that, by western standards, ends in a more typically masculine ending — and then contrasted that with a more feminine-sounding preferred name.

I’m sort of surprised the English version bothered to keep the gender element at all, much less doing that and also keeping the double names; they could have ditched any of that and just written something wholly new, after all. To this day, I’ve wanted to talk with the people in charge of translating Japanese video games for English-speaking audiences in general, but specifically I’ve always wondered who at Nintendo of America made the decision to rename Birdo in the way they did. For what it’s worth, though her western name has endured, Nintendo of America would more and more often just use female pronouns when referring to Birdo without comment or explanation, although you can still find recent examples where she’s given the neuter pronoun or just written in a way that seems to deliberately avoid pronouns altogether.

Clockwise from top-left: SMB2 instruction manual, Doki Doki Panic instruction manual, Super Mario Advance instruction manual, Mario Mania guide. The Doki Doki Panic text translates as “Thinks they're a girl and spits eggs from their mouth. Call them Cathy and they'll be in a good mood.“

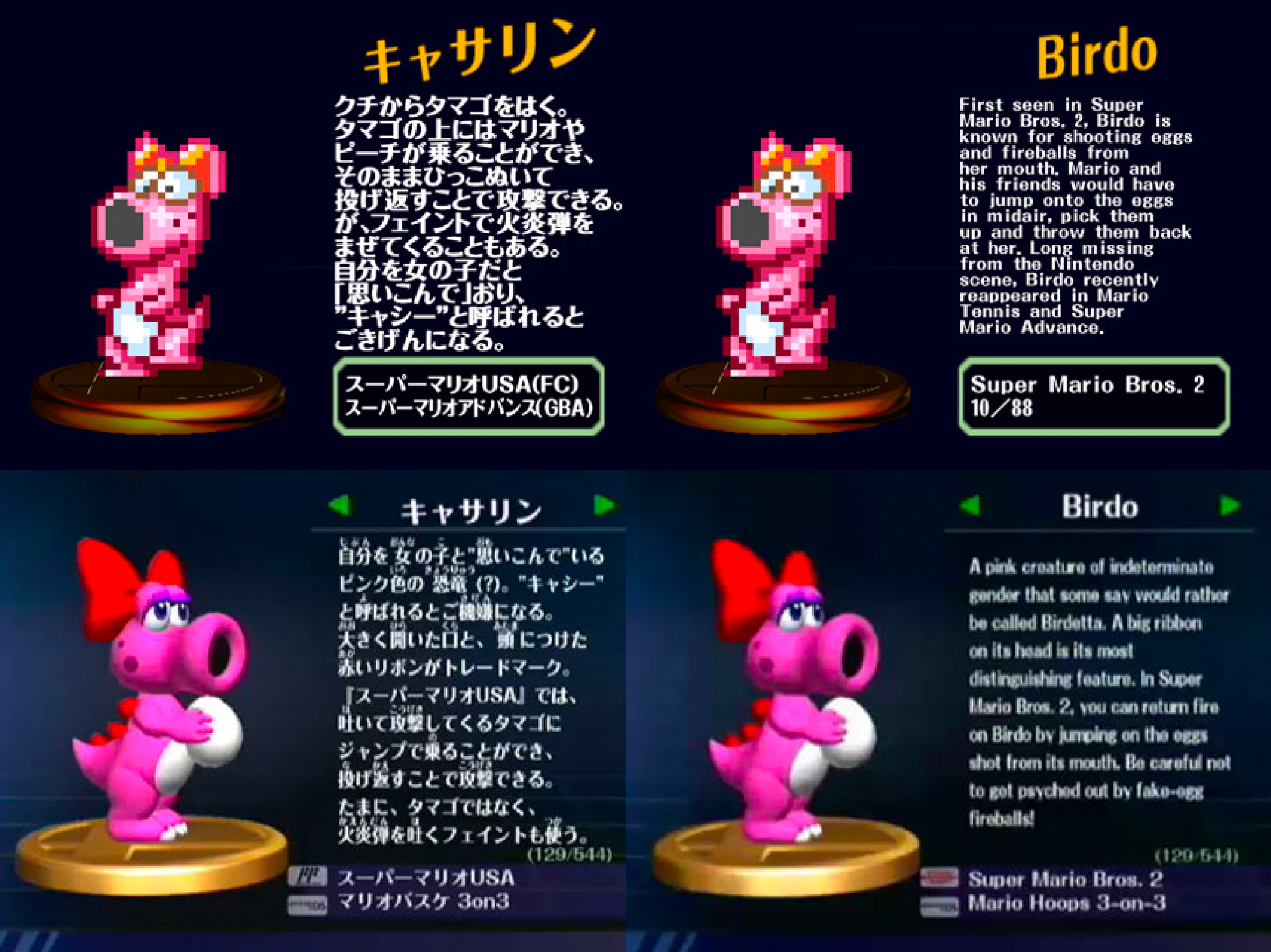

Top: Super Smash Bros. Melee trophy descriptions, with the Japanese text translating as “Spits eggs from their mouth. Mario and Peach can ride on the egg and attack by throwing it back. Also uses fireballs as a feint attack. Thinks they're a girl and likes being called ‘Cathy.’” Bottom: Super Smash Bros. Brawl trophy descriptions, with the Japanese text translating as “A pink dinosaur? who thinks they're a girl. Likes being called ‘Cathy.’ Their trademark is their wide-open mouth and the red ribbon adorning their head. In Super Mario USA, you can return fire by jumping on eggs Catherine spits out and throwing them back. Sometimes they also use fireball feint attacks instead of eggs.” All of these images, BTW, taken with permission from TMK’s Mario in Japan specials on Smash Bros. Melee and Smash Bros. Brawl. Would recommend all their Mario in Japan specials, if you’re into what I’m doing on this site.

You have to wonder if there is an official Nintendo policy on how Birdo should be described.

Because of a famous error in the SMB2 credits, Birdo is often associated with an enemy character who otherwise does not reappear in subsequent games: Ostro, the ostrich-looking baddie that Shy Guys can ride. Remakes of SMB2 no longer identify Birdo as Ostro or Ostro as Birdo in the credits, but oddly the association has persisted: In Italian, Birdo’s name is Strutzi, which would seem to come from the Italian struzzo, “ostrich.” That association is actually one of the ways Birdo works as a kinda-sorta predecessor for Yoshi, which I detail here.

So now we finally get to the character that’s maybe most emblematic of Super Mario Bros. 2: the Shy Guy. You’d probably think that they became a Mario series mainstay, but there’s actually a pretty solid argument for them never appearing in a mainline Mario game following SMB2. I know, I know — you think I’m wrong, but hear me out.

Left to right: Doki Doki panic instruction manual, SMB2, Yoshi’s Island, Paper Mario: Color Splash

The next time Shy Guys show up in a new game, it’s 1995’s Yoshi’s Island, where they looked and functioned mostly like they do in SMB2. If you are objecting to my Shy Guy theory by pointing out that Yoshi’s Island is the sequel to Super Mario World, hence that extended title Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island, I will respond by saying that longer title is mostly a marketing gimmick used to sell Nintendo players on what was essentially the first title in the Yoshi series of video games, which branch off into something different from what characterized Mario games. Your mileage with this theory may vary, but it is interesting how Shy Guys became more of a regular enemy for Yoshi, appearing again Yoshi’s Story and the further sequels that pushed those games into more solidly “This is a Yoshi game” territory. Meanwhile, I think the Shy Guys have appeared in every Mario RPG title as well as every Mario Party and sports title. It’s actually in the Nintendo 64 Mario Tennis where Shy Guy makes his first playable appearance. So yeah, Shy Guys emerged from Doki Doki Panic to become an iconic part of the Mario games, just not so much in the mainline games.

If you’re thinking back and swearing that you could remember a Shy Guy being in Super Mario 64, you’re actually thinking of a similar and related character: the Snifit, a.k.a. a Shy Guy with a gun strapped to his snout. It’s a floating version of the SMB2 Snifit — technically called a Snufit, although in Japanese it has the same name as the regular, non-floating Snifit, ムーチョ — Mūcho, which according to Super Mario Wiki comes from Mū Kai, the name of the setting in Doki Doki Panic + 長 — chō, “military leader” but also other non-military positions of power, such as 校長, “principal,” and 社長, “CEO.”

Left to right: SMB2, Super Mario Advance instruction manual, Super Mario RPG, Snufit in Super Mario 64 DS

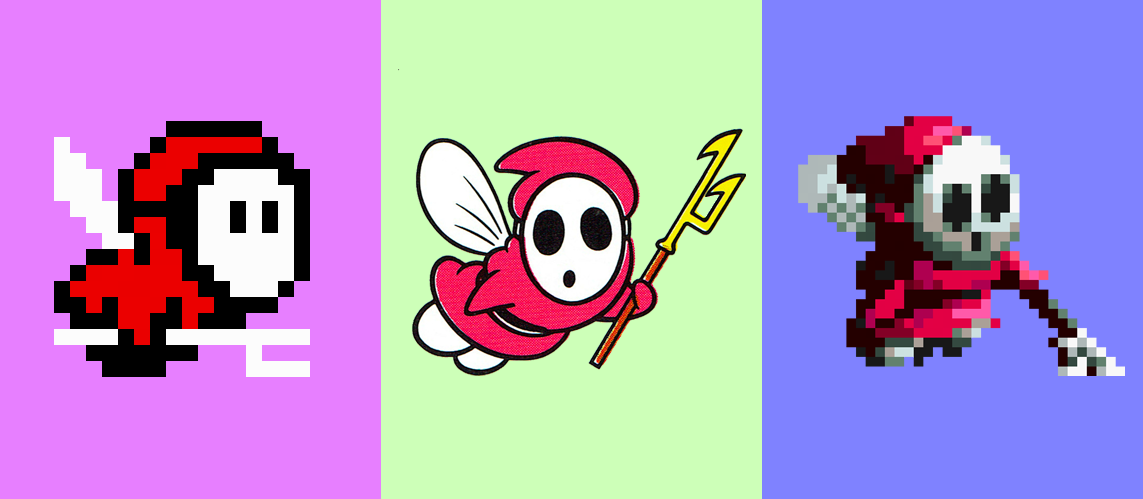

The regular, non-floating Snifit shows up in Yoshi’s Island and most subsequent Yoshi games. There is also the Beezo, a sort of winged Shy Guy armed with a pitchfork, but Beezo only appeared subsequently in Super Mario RPG — and even then being called Shy Away for now reason I have ever understood. I would imagine the propeller-topped Fly Guys replaced Beezos starting in Yoshi’s Island.

Left to right: SMB2, Super Mario USA instruction manual, Shy Away in Super Mario RPG

In Japan, the Shy Guy is known as Heihō — an apparent pun on hohei, “foot soldier” and which is also the noise they make now. And the Beezo is トンダリヤ — Tondariya, which the Super Mario Wiki says comes from tonda, the past tense of the verb meaning “to fly” and yari, “spear.”

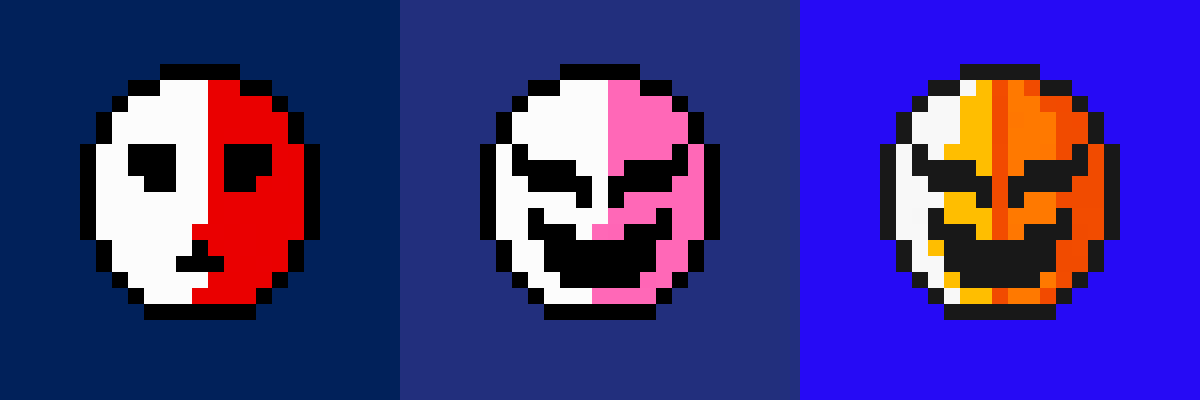

And that brings us to Phanto, the cause of much anxiety for children playing Super Mario Bros. 2 back in the day and a memorable enough part of the game that I’m surprised he didn’t end up recurring. Phanto is a demonically grinning mask — one of many, many masks in SMB2 — which shudders to life when Mario picks up a key and then doggedly flies after him so long as he’s holding the key.

Left to right: Doki Doki Panic, SMB2, Super Mario Advance

Aside from the cameo in Mario Kart 7 mentioned in the first post, Phanto does not return to give players nightmares until Super Mario Maker 2, where Nintendo finally re-implemented the gameplay element of “steal a cursed key, run like the devil is chasing you.” I’m surprised it took this long. In Japan, Phanto is カメーン, Kamēn, from — 仮面, kamen, “mask.”

The rest of the enemies don’t reappear outside of direct remakes of SMB2. But here’s a list of them with whatever notes I could possibly come up with.

Clockwise from top-left: Spark, Trouter, Flurry, Panser, Porcupo, Albatoss, Tweeter, Autobomb, Ostro

The game has these flashing enemies that buzz around the perimeter of a given platform, usually in indoor stages. They’re called Sparks, and that makes them sound very similar to a slightly more recurring baddie that debuts in Super Mario World: Li’l Sparky. Pretty much the only reason this enemy is known today is that in Paper Mario, a Li’l Sparky named Watt joins Mario. Otherwise, they only appear otherwise in Mario & Luigi Superstar Saga and Super Princess Peach, which means they are fairly obscure in the grand scheme of Mario characters, just slightly less obscure that these SMB2 Sparks, which based on their Japanese names seem to be different characters. In Japan, the SMW character is ケセラン — Keseran, after the yokai Kesaran-Pasaran, while and the SMB2 character is スパーク — Supāku, obviously “spark,” which is the same name as yet another similar enemy in Donkey Kong Jr., but again, I’m thinking seems to be a different design based on same basic idea.

Trouters are fish that leap vertically into the air to act as obstacles or stepping stones, but they’re never seen again. In Japan, they’re トトス — Totosu, possibly a portmanteau of toto, a childish word for fish, and tosu, “toss.”

Flurries, the slippery ice level baddies, simply never show up again, and for no good reason. In Japan, they’re ナカボン — Nakabon. which Super Mario Wiki surmises is from 仲 — naka, “go-between” + 坊 — bon, “boy” or “sonny.”

Autobombs are the rolling contraptions that Shy Guys sometimes ride and which back in the day I called “MTV Cameras,” since they look like a piece of video equipment. Years later, I’d realize that the M stands for Mamū. They’re not seen again. In Japan, it’s ターボン — Tābon, which according to Super Mario Wiki could be from "turbo" and ボンボン— bonbon, an onomatopoeia describing “repeated hits or bursts,” which makes sense because they’re not actually video cameras but machines that shoot fireballs.

Ostro never shows up again, except for in association with Birdo and in the sense of being a Marioverse beast of burden years before Yoshi showed up. Its Japanese name, ダウチョ, Daucho, comes from 鴕鳥 — dachō, “ostrich.”

Panser, the fire-shooting flower enemy, has the unique distinction of being the only common SMB2 enemy that doesn’t even show up in the Super Mario Bros. cartoon. The Mario Kart 7 cameo mentioned in the first post is as close as it gets to a repeat appearance anywhere other than a direct SMB2 remake. At least today I can appreciate whoever came up with its name, which is presumably portmanteau of pansy and the Panzer army tank. Its Japanese name, ポンキー, Ponkī, comes presumably from ぽんぽん — ponpon, an onomatopoeia that can mean a lot of things though most often used to signify gentle pats or soft bouncing. Ponkī is also the name of a different fire-shooting plant enemy in Super Mario World that in English we call the Volcano Plant.

If Shy Guys are the Goombas of SMB2, then Tweeters, the hopping bird enemies that look like they’re wearing plague doctor masks, are the Koopa Paratroopas. Plentiful in their debut game, they never show up again, though their Super Mario All-Stars sprite shows up in the source code for Yoshi’s Island. It’s argued here that Tweeters form the base of the totem poles in the Sunset Wilds stage in Mario Kart: Super Circuit, but it looks more like one of Kamek’s underlings to me, even if the stage is Shy Guy-themed and if the poles themselves are otherwise made from SMB2 enemies.

Super Mario Wiki guesses that Tweeter’s Japanese name, リートン, Riton, is a play on either リトル — ritoru, “little” or 鳥 — tori, “bird.”

The Super Mario Wiki thinks the porcupine obstacles in the Yoshi Valley course in Mario Kart 64 are supposed to be the same character as the SMBS Porcupos. I say maybe, but also sometimes a porcupine is just a porcupine. Porcupo’s Japanese name is ハリマンネン, Harimannen, which clearly comes from ハリネズミ — harinezumi, either “hedgehog” or “porcupine” and literally translates as “needle mouse.” The Super Mario Wiki entry connects it further to 万年 — man'nen, “ten thousand years” — though I’m not sure why and am all ears if you can explain the connection.

Do the whales count as enemies? No, of course they don’t.

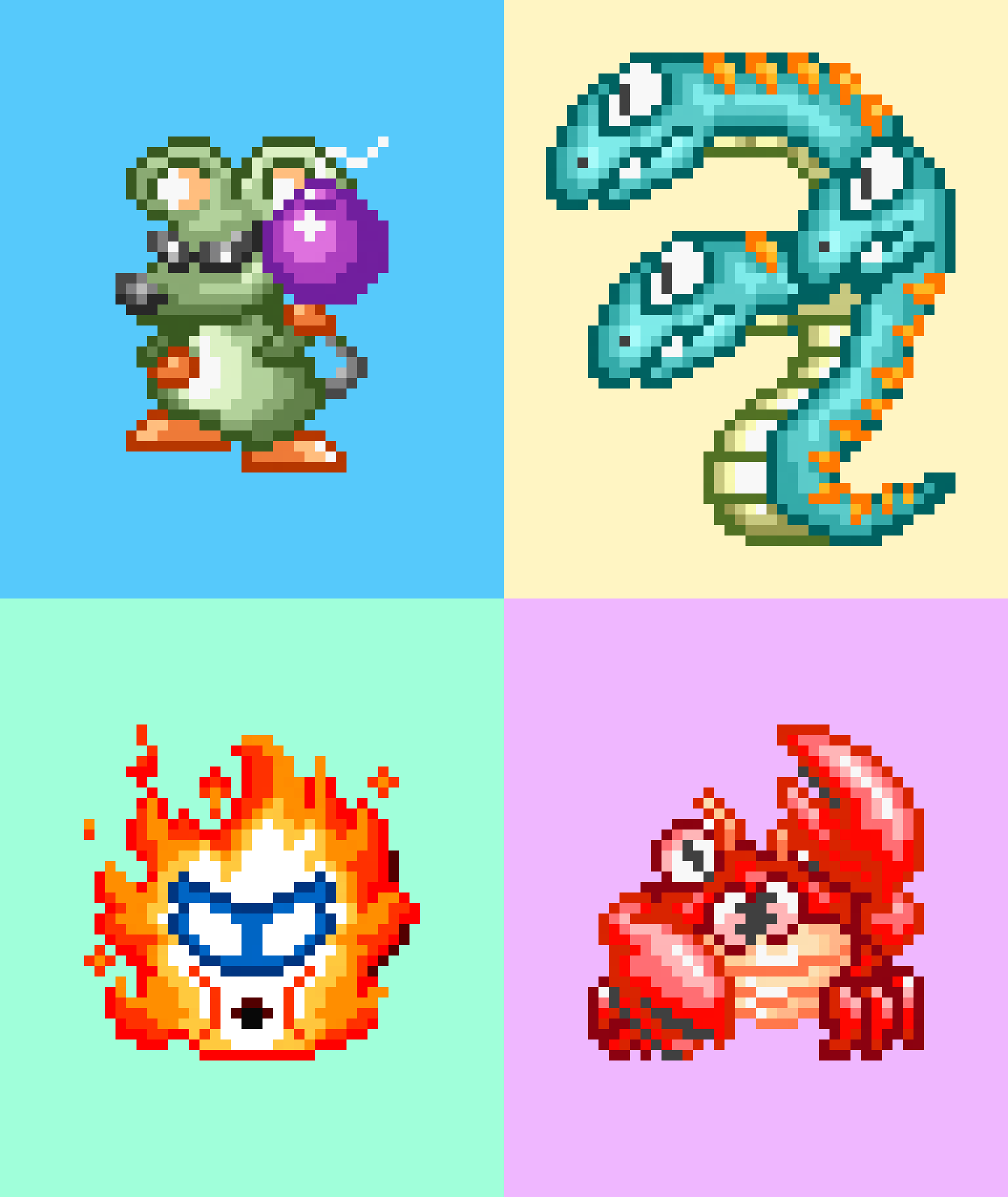

While Super Mario Bros. 2 features a variety of end-of-world bosses, none of them ever show up again in any meaningful way in a game that wasn’t a direct remake. In fact, the one connection any of them ever get to anything outside the confines of SMB2 is that Clawgrip, the rock-tossing crab boss who actually does not exist in Doki Doki Panic was uniquely invented for the western version of the game, is depicted in the remake Super Mario Advance as being a common Sidestepper crab enemy from the original Mario Bros. until bubbles — presumably like the ones Wart makes — transform it into its bigger boss form. The Cutting Room Floor indicates that at some point the game was going to do something similar and have pre-monstrous forms of the bosses Mouser and Tryclyde: a mouse with a unique sprite that may be a modification of the Porcupo sprite and a Cobrat colored teal to match the new color scheme Tryclyde got in that game. Oddly, the effort to give these three boss characters cuter, smaller forms would put them in line with Fry Guy, the remaining boss in the game and a living ball of fire that actually had a smaller form even in the original game; when he takes enough hits, he devolves into a group of smaller flame enemies. Not that it warranted him a repeat appearance.

Clockwise from top-left: Mouser, Tryclyde, Clawgrip, Fry Guy.

Clawgrip’s name upon traveling back to Japan for Super Mario USA became チョッキー, Chokkī, from チョキチョキ — chokichoki, the sound of snipping. Fry Guy’s name is Japan is ヒーボーボー, Hībōbō, from 火 — hi, “fire,” and ボーボー, bōbō, the onomatopoeia for the sound of crackling fire. Tryclyde’s name in Japan is ガブチョ— Gabucho, From がぶがぶ — gabugabu, onomatopoeia for biting, though I’ve always wondered where his English name came; the first syllable is clearly just referring to the fact that he has three heads, but why “Clyde”? In Japan, Mouser’s name is ドン・チュルゲ — Don Churuge, the latter part coming from チュー, chū, onomatopoeia for the squeaking of mice and the former part, according to Super Mario Wiki, coming from either the Spanish honorific title or another Japanese onomatopoeia representing a bang, boom or thud, which would makes sense given that Mouser throws bombs. Although Mouser had yet to appear in another game, he did appear as part of Nintendo’s Kinopio-kun greeting card for 2020, which was the year of the rat.

And that leaves us with Wart, the first non-Bowser big bad in a Mario platformer, who never shows up again in another Mario game, save for the briefest of cameos in Super Mario Maker 2. That’s it — which is to say, it’s not a whole lot. I’m kind of surprised he hasn’t had a return to the spotlight all these years later, though I wonder if the chances of that happening have been compromised somewhat by the re-emergence of King K. Rool, who looks a bit like Wart.

Clockwise from top-left: SMB2, Super Mario All-Stars, Link’s Awakening (Switch), Super Mario Advance instruction manual.

Oddly enough, Wart has had about as much mileage from the Mario games as he has from the Zelda games, as he appears in the similarly dream-themed Link’s Awakening under his original Doki Doki Panic name, Mamū. And because Link’s Awakening gets remade about as often as SMB2 does, Mamū has been longer-lived than you’d expect. According to the Super Mario Wiki, Mamū’s name is either a riff on 夢魔 — muma, “nightmare” or even “incubus or succubus,” which makes for a mental image I don’t want. The name could also come from 魔 — ma, “demon” + 夢 — mu, dream. At the very least, his Zelda appearances allowed him to be realized in a whole new art style with the Switch remake of Link’s Awakening.

While Wart did appear in the tie-in comics, he did not appear in the animated Super Mario Bros. Super Show. Curiously, concept artwork for the show does feature a frog-like enemy wearing a pendant that looks a lot like Wart’s, although he is purple and rendered more in the gurgly, grotesque style that we’d see on Captain N: The Game Master.

Really, really, really weird. Whoever made this, I salute you.

So what have I accomplished in cataloging all this information into one place? Well, aside from telling you without telling you that I needed a non-podcast-related project to occupy my time during a pandemic lockdown, I thought it would be interesting to look what from Super Mario Bros. 2 made the cut and what didn’t. Was that a worthwhile use of my time? Maybe! If anything, the notion of putting together a retrogaming blog that answers the where, why and how of weird little video game bits is something I’ve wanted to make for a while, and this seemed like as good a way as any to get it started.

I feel like the supremacy of Super Mario Bros. 3 goes unquestioned today. It was a big deal on its own, and you can clearly see how concepts introduced in that game got refined and tweaked for Super Mario World — itself another big deal. It’s also easy to see Super Mario Bros. 3 as a grand evolution of the first Super Mario Bros., and honestly it was, because in Japan the western SMB2 did not become part of that lineage until after the fact. That doesn’t mean that SMB2 is wholly separate from the franchise, and in a way I suppose I made these two posts as a response to the naysayers I met online way back when, who didn’t think much of the game or what it added to later sequels. Not only does it matter, but I at least care enough to count the ways. At the same time, SMB2 truly does not fit with the rest of the series. When it hit shelves, no one was fully clear what constituted a Mario game, and as Nintendo figured out what went into every subsequent release, SMB2 actually seemed even stranger than it did in 1988. It still does. It’s an outlier, just one that shouldn’t be discounted.

If you wanted to have Big Thoughts about this game, I suppose it’s meaningful that when you beat it, you discover it was all a dream — that none of what you (or Mario) just experienced technically happened. Nintendo wouldn’t have known at the time that so much of SMB2 would end up going by the wayside, only to creep back into the main Mario canon years later. In that sense, it does actually work life a a jumbled up dream that breaks the rules of reality — “Wait, jumping on top of enemies *doesn’t* kill them???” — and then fades out of your mind as soon as it’s done, save for the occasional flash of something deep in your brain. You can just dismiss it as something that didn’t really happen, that’s not important but I clearly think it’s a lot more interesting to delve into the weirdness of it all — dreams and this game alike — to see what of value there is to pull out of it.

May Phanto watch over you.