You Cannot Grasp the True Form of Giygas!

Generally speaking, if you’re in the final battle against the main villain of a video game and you’re told you cannot grasp the true form of his attack, that’s not good news — for the little characters existing in the game or for the human controlling them. But it might also be a hint that the game is operating on a deeper, weirder level.

As a special Patreon feature, the video game podcast Nintendo Cartridge Society has begun playing through titles that the hosts haven’t yet beaten, and a recent entry in this series is about Earthbound, the Nintendo RPG released for the Super Famicom in 1994 and for the Super NES in 1995. Speaking as someone who played this game back in the day, I think it is truly wild that Nintendo allowed this game outside Japan — not because it’s in any way inferior, but just because it’s so incredibly weird. It’s about America, to an extent, but its sense of humor is distinctly Japanese. Its graphics evoke the 8-bit era of our childhoods, but the plot goes to some very dark, very grown-up places. It’s a mishmash of pop culture shout outs, allusions and sometimes even direct audio sampling, but a lot of things being referenced would not have been familiar to the target demographic for when the game first hit shelves.

And then there’s the final boss, which defies expectations in a few different ways. As I’m going to argue in this piece, that is perhaps the point. Not only was this unexplored territory for the subject matter covered in video games at the time, but also it suggests a more profound philosophy underpinning Earthbound than might be apparent on a casual playthrough.

Yeah, this one is going to get weird.

Cosmic Horror and Etymological Mystery

As the Nintendo Cartridge Society hosts point out in their Earthbound discussion, one of the confusing things about the game’s main villain is that it’s not at all clear how to pronounce his name. Giygas, he’s called, and from early on in the game, characters will mention his name, but as an English-speaker, I have to say that this string of letters could be pronounced any number of ways. Guy-gass? Ghee-ee-gus? Jeeg-us? It really could go any number of ways.

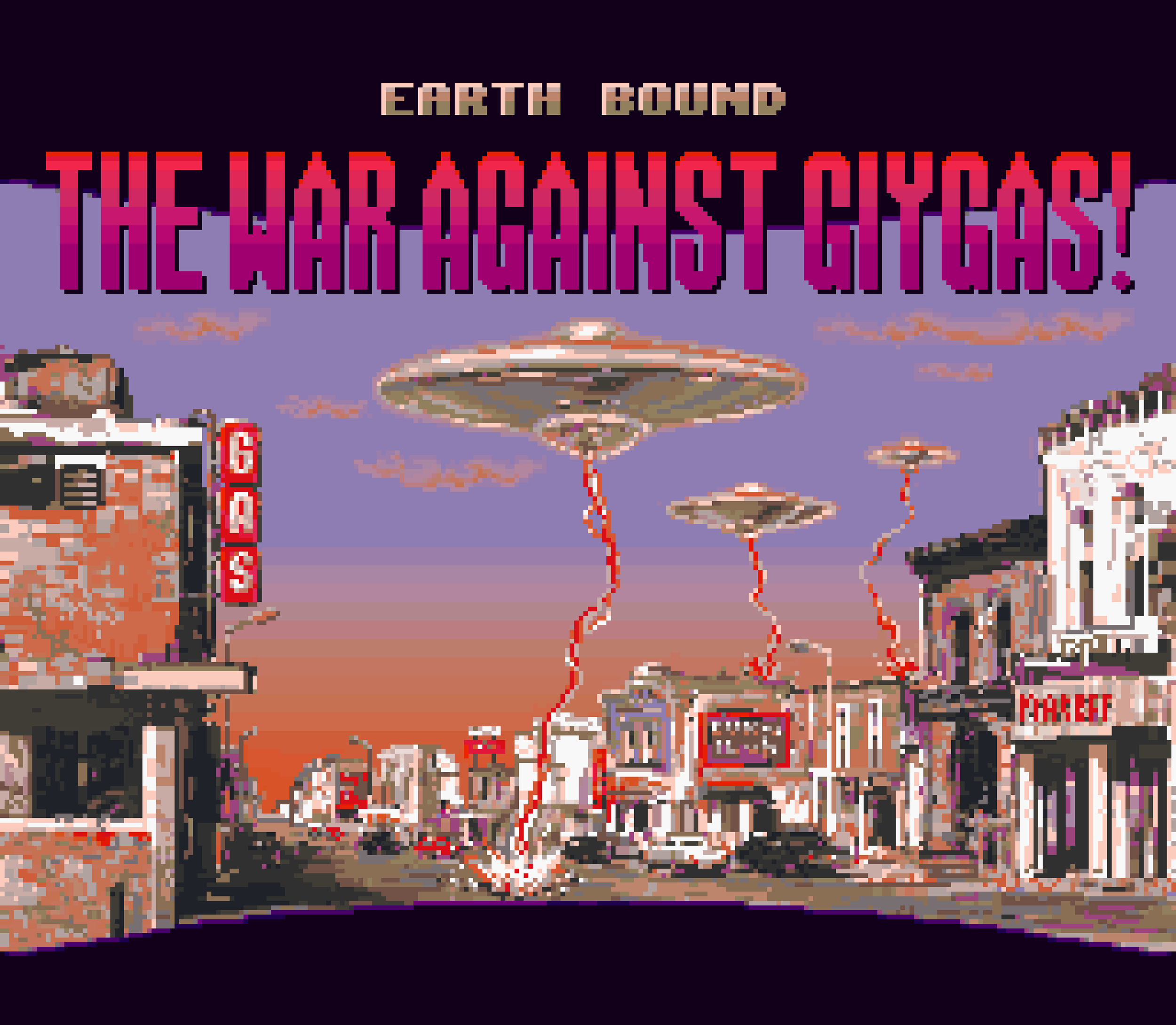

The title screen to the English version of Earthbound. You have to wonder if the prominence of the sign reading “GAS” might have influenced how players pronounced the second syllable of Giygas’s name. And no, despite what you might guess, this screen is apparently not a digitized version of an pre-existing image but instead was an original composition by art director Koichi Oyama, made specifically for the game.

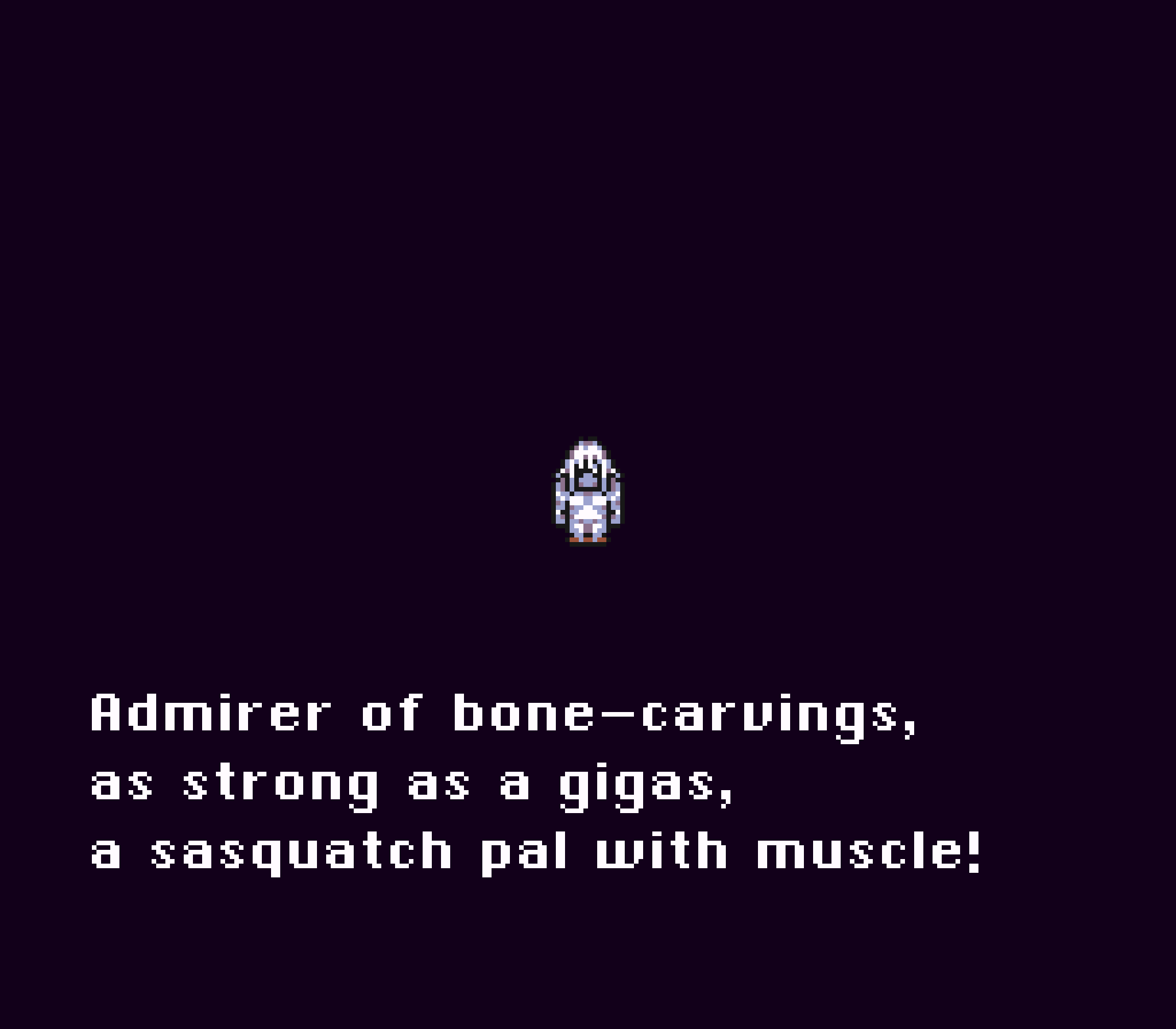

Myself, I was always inclined to pronounce it “ghee-gəs” because the previous year, I’d been exposed to what seemed like a more conventionally spelling of the word in another Super NES RPG: Final Fantasy VI. If you’ll recall, this game gives every party member an intro where the screen goes black and onscreen text offers a sort of background info haiku. In the case of Umaro, a sasquatch who’s one of the secret characters in the game, the localized text includes the word gigas, as if that’s supposed to mean something to the person holding the controller.

For what it’s worth, the original Japanese text does not mention the word gigas, and this site translates it as “A yeti who loves bone carvings / His strength can mow down massive trees / ...but he's fairly rowdy.”

Again, I played this back when I was twelve, and I had no idea what a gigas was supposed to be, but just from context, you can infer that it’s something unusually strong. What’s more, having this weird vocabulary word bouncing around my head made me think that the name of Earthbound’s big bad should be pronounced the same, that extra “y” notwithstanding. Because obviously a final boss in an RPG is also a strong, scary thing.

Right?

Well, kinda. First up, gigas isn’t traditionally an English word, and I’m not even aware of it getting used in fantasy literature outside of the Final Fantasy VI script. However, it is the singular Greek word that gets pluralized as gigantes and which gives English its word giant. It refers specifically to the oversized mythological offspring of Gaia and Uranus that weren’t the Titans, Cyclopses or the Hecatoncheires. So a gigas is a giant, essentially, and it makes sense that the hulking sasquatch from Final Fantasy VI would be as strong as one, and I guess just from the standpoint of giants being imposing, dangerous figures, it would also explain why Earthbound’s big bad would be named after one.

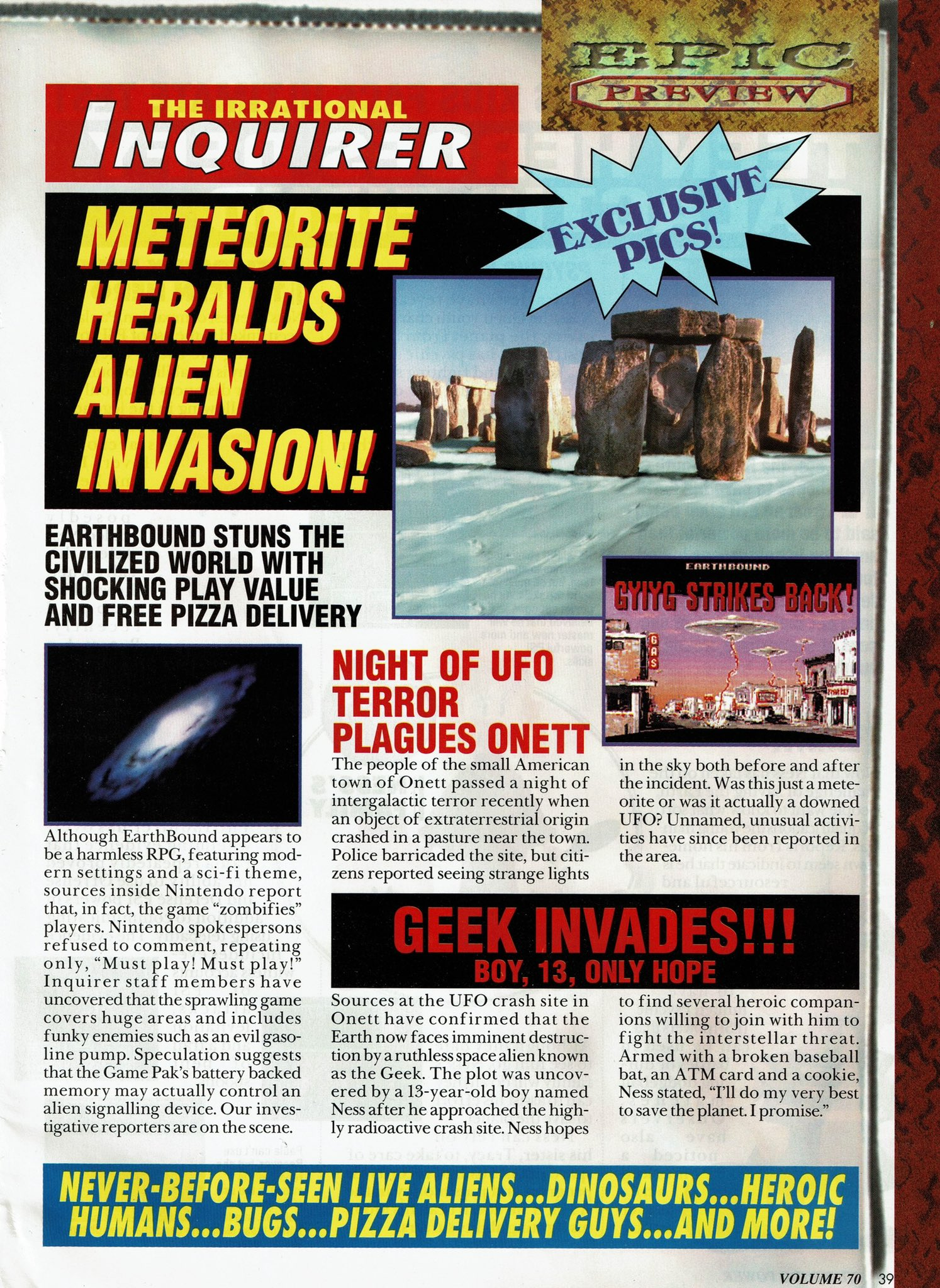

However, when you look at Giygas’ name in Japanese, things get a little more complicated. Its Japanese name, ギーグ (literally Gīgu), is usually rendered in English as either Giegue or Gyiyg. According to Clyde Mandelin, whose book on Earthbound is the not only the best thing written about this game but also one of the best things written about game translation in general, localizers working on Earthbound at one point were considering Geek or The Geek as possible ways to refer to this monstrous thing in English before deciding that this did not sound scary enough.

Even Nintendo’s official publication referred to this character using these names in the March 1995 preview for the game.

The June 1994 issue of Electronic Gaming Monthly, meanwhile, just gives the bad guy’s name as Geeg — and Ness and Nes.

Whoever wrote these captions should go to jail.

Madelin’s book quotes an interview with series creator Shigesato Itoi where he says that the name was chosen to make the player think of something that was both big and unpleasant, essentially.

He couldn’t have just any old name — it needed to be something frightening, you know? So I tried to come up with a name that sounded unpleasant to the ears and hit on the sound “ghee.” It’s unpleasant for sure. “Ga-gi-gu-ge-go” has a particularly dreadful sound to it, wouldn’t you agree? Much more than “pa-pi-pu-pe-po” at least. … One other meaning is the word giga, which is larger than mega. We were in the era of megabyte games at the time, so I basically thought, “In that case, I’ll make this game giga!” In effect, the name Gyiyg is an invention that mixes the ideas of “enormous” and “dreadful.”

In that sense, the English name is especially apt, because it’s even closer to the “big” sense of Itoi was striving for. That Greek word gigas is, in fact, the source of the word part giga- that you see in gigabyte and gigaton, and it specifically means ten to the ninth power. And while I think everyone is in agreement on how those words are pronounced, the connection to gigas and Giygas isn’t as strong, so we aren’t sure to use gigabyte and gigaton as a pronunciation guide.

Essentially, the localized name sought to solve a problem — that the bad guy’s name didn’t work in English as is — and while it arrived at a good solution, it managed to preserve an element of mystery, of unknowableness, that’s entirely appropriate for how this thing functions.

The Policeman and the Misremembered Movie

Heads up: This section discusses a cinematic rape scene.

The name confusion, however, is far from the only mystery associated with Giygas.

There’s another one I wanted to explore in this post, and it has to do with sex and gender — and similar to the confusion about how to pronounce his name, there’s a lot of ambiguity with this one. At its core is something that’s both true and sort of not true, depending on how you look at it. Even so, it’s nonetheless part of the culture surrounding this video game villain.

If I were to ask most Earthbound fans if they knew of a connection between Giygas and anything sexual, they’d probably point to the dialogue he gets during the final battle. The in-universe explanation is that Giygas’s mind is shattering under the pressure of his rapidly expanding psychic powers, causing him to speak incoherently. The text is suitably disturbing — and not explicitly sexual on its own, though someone playing the game could easily make that connection.

It hurts, Ness…

…I’m h…a…p…p…y…

…friends…

…It hurts, …it hurts…

Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness, Ness…..

…go… b… a… c…k…

….Ness…

I feel… g… o… o… d…

…I’m so sad... …..Ness

Ness!

Ah, Grrr, Ohhh…

Argh… Yaaagh!…

It’s not right… not right… not right…

The stuff of nightmares, right? Especially for a Nintendo title in 1995!

Now, one of the many urban legends surrounding Earthbound stems from this dialogue. It’s at least somewhat Shigesato Itoi’s fault, too, because in 2003, the Japanese website 1101.com interviewed Itoi about the origins of the franchise, and he recalls Giygas’s lines being inspired by an incident in which he, as a child, wandered into a movie theater screening the 1957 film Kenpei to Barabara Shibijin (憲兵とバラバラ死美人, “The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty”) and witnessed what he recalls as a rape scene. It’s since been noted that no such scene exists as he describes it. For his Earthbound Central website, Mandelin posted the scene Itoi seems to be referring to, which shows a woman being strangled and in a state of partial undress, but it’s not a rape.

I don’t think Itoi has ever circled back to discuss the movie and his apparently faulty recollection of it, but it’s not hard to imagine how this scene could have disturbed a child to the point that he misremembered it as depicting rape. However, a longstanding urban legend states that Itoi lifted the dialogue from this alleged rape scene and had Giygas speak it in the game’s final battle. Again, the mistake is at least partially Itoi’s fault, as he seems to be implying that in the 1101.com interview:

It was rape, after all. On the riverbank. In the film. When he grabbed her breasts, they were distorted like balls. It was a direct hit to the brain. … In other words, there is a sense of horror when crime and eroticism are side by side, and that is [Giygas’s] final line. In it, he says “[it hurts].” That’s… breasts. It’s like — how shall I put it? — a raw sensation.

The way the quote reads, it seems like he’s saying he lifted the line from the film and gave it to Giygas. That doesn’t seem to be the case, especially since no one speaks a line like that in the film, to say nothing about a woman’s breasts being violently manhandled in the way he describes. The story gets told this way regardless. What’s more, the legend has grown to include the idea that visual imagery and a musical motif in the scene inspired elements in Earthbound. They apparently didn’t, despite what you’ll read elsewhere online. (Mandelin’s page is very clear on the matter, for what it’s worth.)

Again, the truth of the story lies in some shade of gray. Itoi remembered wrong, but his apparently false memory did inform Earthbound’s final battle, although not to the extent everyone seems to think. The most heightened urban legend version of the the story persists nonetheless, and I can understand why: It’s exactly the kind of story filled with lurid details that humans love, with the capper of “this thing you remember from your childhood is more fucked-up than you realize,” which is the thesis of a lot of viral internet content.

I think there might be another reason people keep telling and retelling this story, even when you can fact-check the details online, and that is because the link between Giygas and all things sexual exists on an even deeper level.

The Mysterious Woman — Giygal?

In the previous section, I mentioned how people tend to run with urban legends about Earthbound, pulling details out of the game that its creators never intended. In general and not specific to Earthbound, this is a common human pastime — especially when the details relate to sex, because we often think about sex so much that we find traces of it in the most inexplicable places, pareidolia-style. That said, I think people like to do it with Earthbound more than other games because its unique art style makes it look so childlike and innocent that it feels subversive to overlay more adult themes on it, even when the plot of the game is offering the dark and sinister fairly explicitly. (In a sense, you could say that the whole of Undertale stems from one creator’s desire to use Earthbound as a template for telling an even stranger story.)

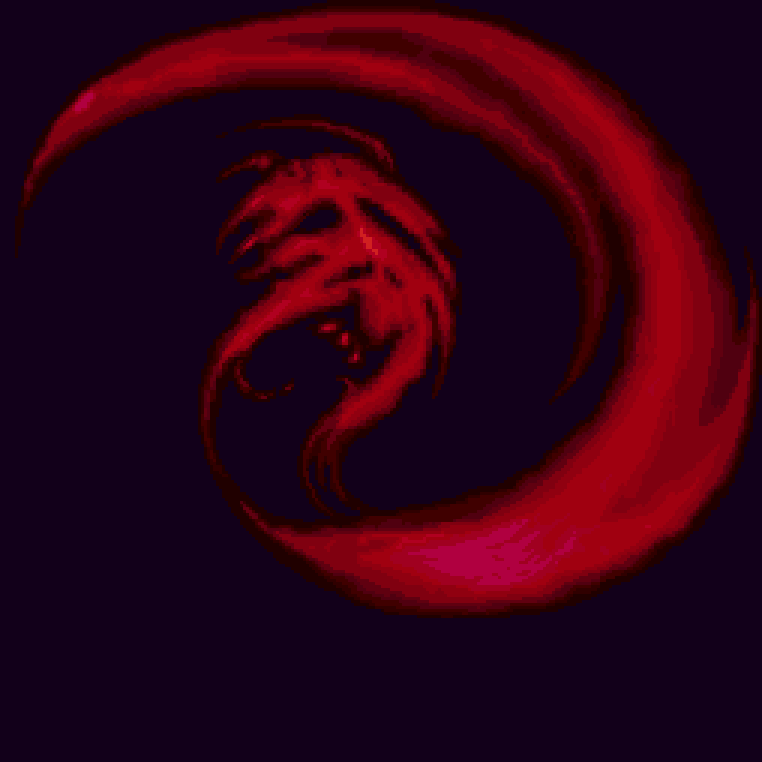

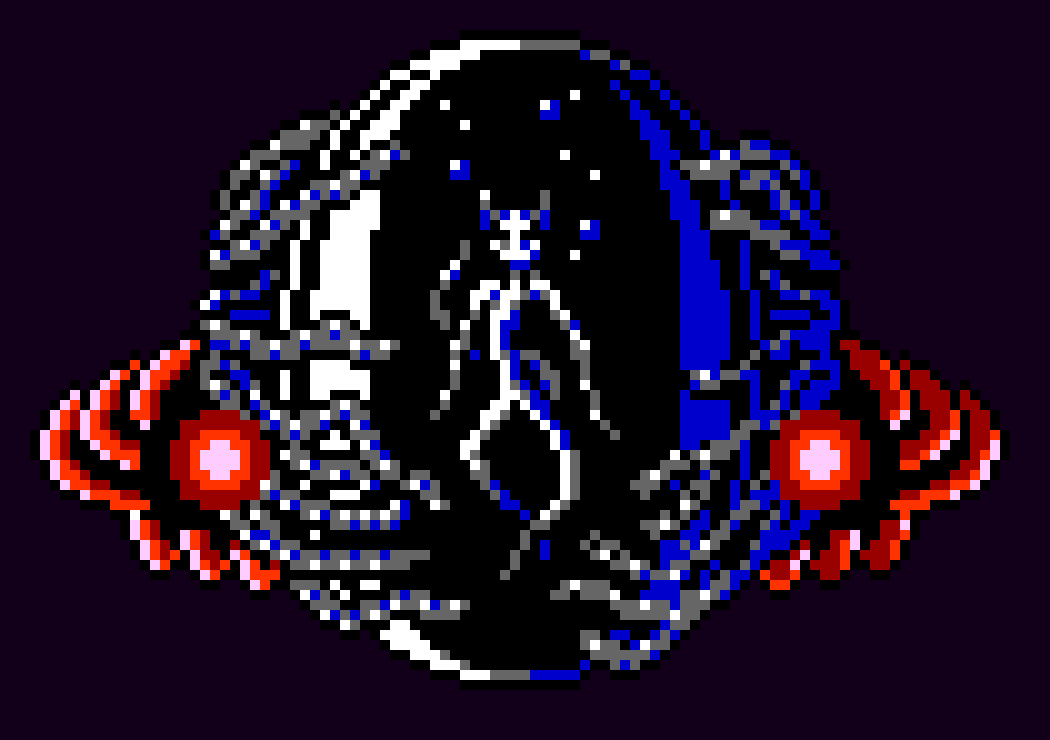

As an example of one of the more notorious bits of Earthbound lore, more than a few people insist that there’s something fetal to Giygas’s appearance. Specifically, the way Giygas appears during the final battle looks like an ultrasound — perhaps an ultrasound showing an unborn child. If that’s true (and I’m not saying it is, but go with me), then Ness and his friends beat the game by taking out something that’s still in utero. It’s the “Giygas abortion” theory.

As a childless adult, this is how I see literally every expectant friend’s ultrasound of their forthcoming child.

Except that’s not how we were supposed to see it, at least according to a 2013 Kotaku interview with Marcus Lindblom, who wrote the English localization for Earthbound and who in the following quote is responding to a question about the abortion theory. “I think that this is a great instance of people reading in stuff that was probably never really intended,” Lindblom says. “There’s certainly nothing wrong with people doing that kind of thing. In reality, as far as we were ever concerned, nothing like that ever came up.” Although the original creators would be better able to say whether anything like this was intended, I’m willing to believe that Lindblom is correct. However, if you wanted to argue that he’s wrong, there’s a good amount of evidence to counter him.

For example, there’s a plot point in The Military Policeman and the Dismembered Beauty that’s not evident in the clip: The female victim, Yuriko, is pregnant with her lover’s child when he kills her. That’s not part of Itoi’s recollection of the film, but then again, a lot of the details he does remember aren’t actually in the film, so it’s evident that unconscious and subconscious factors figured into his creative process, even if he didn’t realize that at the time of the interview.

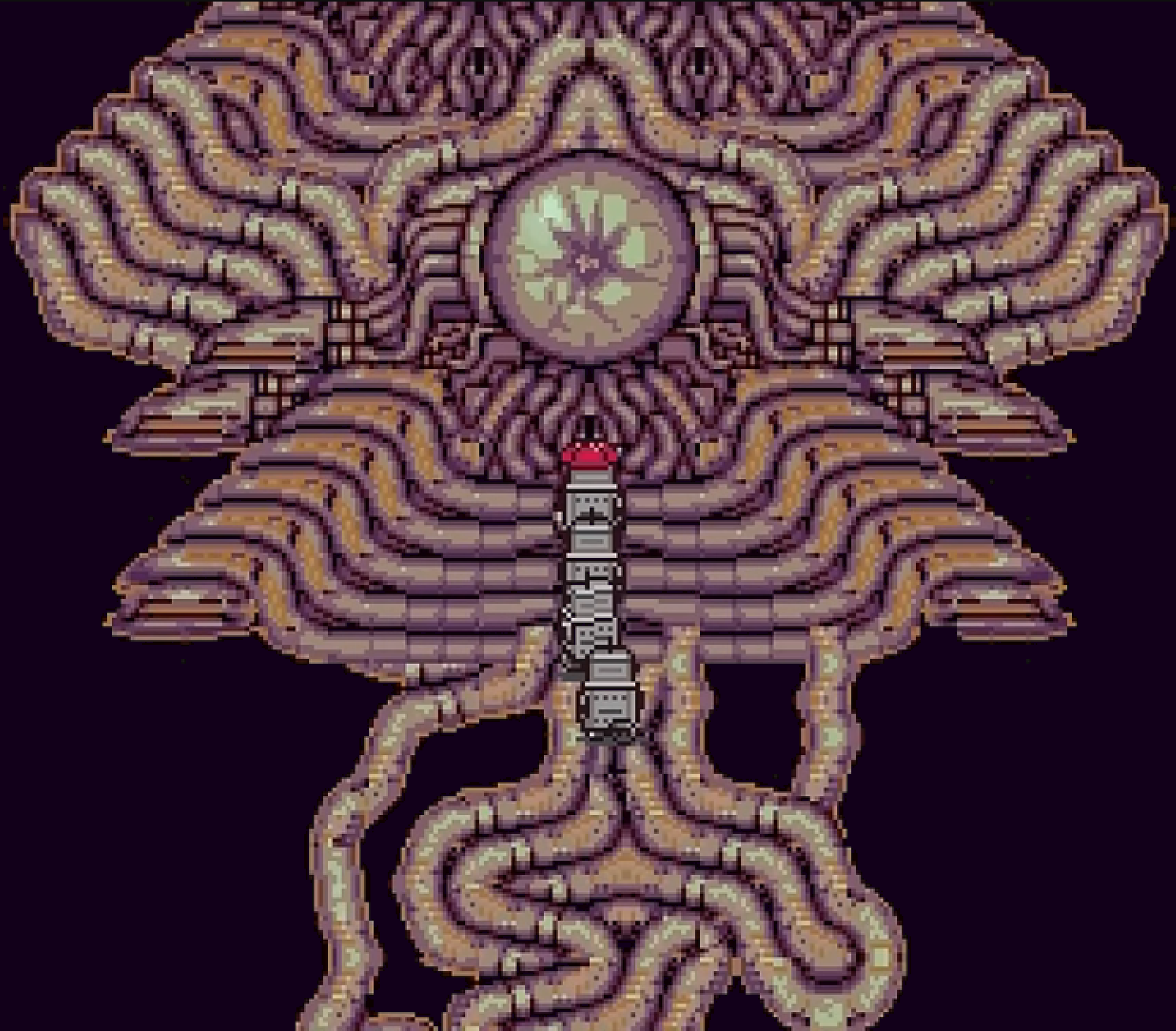

What’s more, Giygas’s ultrasound-looking appearance isn’t the only visual element in the game’s final dungeon to evoke the female reproductive system. The setting of the final battle is the so-called Devil’s Machine, an H.R. Giger-esque fusion of biological and mechanical elements that houses Giygas. It’s been pointed out that in general the shape of the thing suggests the female reproductive system, with the centerpiece of the contraption looking a lot like a cervix — and it’s perhaps meaningful that shortly before the final battle begins, Ness’s face appears in the center of it.

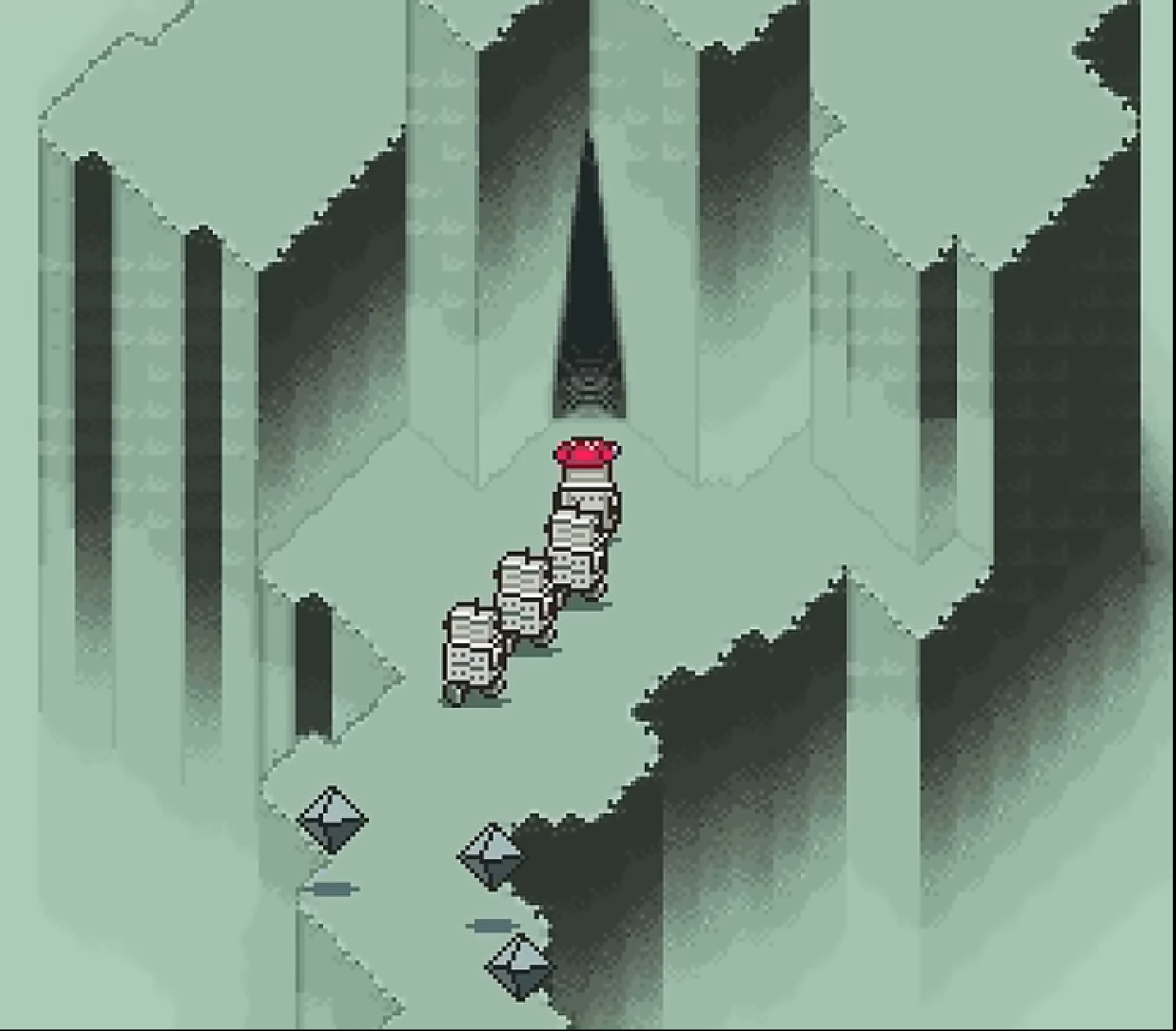

It’s not the only part of the map that gets read in this way. Leading up to the chamber that contains the Devil’s Machine is the Cave of the Past, and the gateway between the two also looks a little… well, anatomical, though more subtle than the robo-cervix.

It’s a type of structure unique to this spot in the game, at the very least. Other Earthbound caves don’t look like this.

It’s enough to make you wonder why the Japanese title for this series is Mother. The three games offer no shortage of options. In each, the main character’s mother plays a role in the story — although Hinawa in Mother 3 most of all. All three games are about saving the whole of planet Earth, which is a metaphorical mother to humanity, and it’s probably not coincidental that the title screen for the first two installments subs in the globe to represent the “O” in the game’s name. Earthbound Origins features a character, Queen Mary, who is an all-important mother figure to various characters. And in a 2003 promotional Itoi himself stated that the 1970 John Lennon song “Mother” was a major inspiration. In February 2024, however, Itoi further clarified that his choice of title stemmed from the fact that his parents divorced when he was very young and he consequently grew up without a mother. He felt such trauma from this that he wouldn't say the word mother, though he found some catharsis in hearing Lennon scream the word in his song “Mother.”

It’s all very weird — potentially interesting, if you’re operating on my wavelength — but what could any of it mean? Surely, this focus on the female part of the reproductive system couldn’t mean that Earthbound’s big bad is female. Could it? Well, here’s where I turn from someone who’s merely documenting the Earthbound fan lore into someone who’s actively adding to it. In my defense, I’m doing it in an attempt to solve a longstanding Earthbound mystery that isn’t one that gets the most attention, but for what it’s worth, it is one that exists entirely within the game itself — no “reading in” needed.

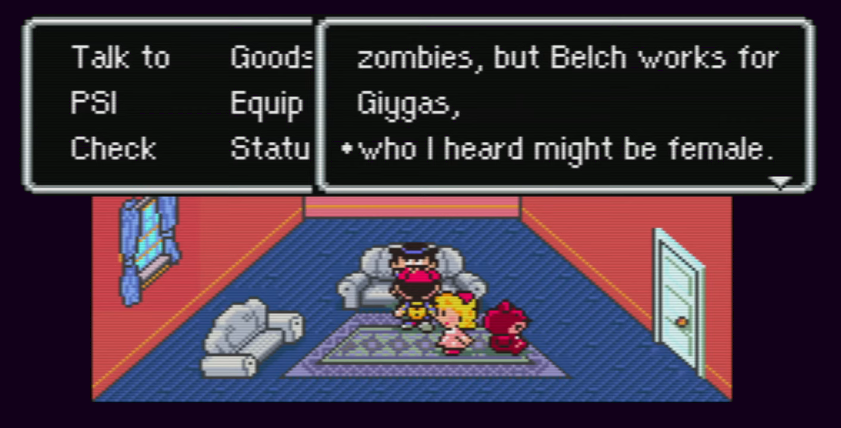

In Earthbound, the third city that Ness ventures to is Threed, and when he arrives there, it’s beset by zombies. Ness and his first traveling companion, Paula, can talk to the townspeople, who are none too happy about their zombie plague, and before the plot advances, a resident who lives in a pink house offers up some surprising insight. He explains that he worked for the zombies in the past, but he also betrayed them, because he’s that sort of guy. The zombies were raised from the dead by something called Master Blech, but Belch is just an underling working for Giygas… “who I heard might be female.” He then follows up with, “Well, I’m not really sure whether Giygas is a male or a female.” It’s a weird exchange but really no weirder than anything anyone else in this game says. What’s more, it’s easily missable. If you don’t swing by the pink house to talk to him, you’d easily advance through the rest of the game without this information. The closest you get to info like this from anyone else is from another random Threed townsperson who reports that he saw the zombies walking in the company of a “suspicious woman” but nothing about Giygas.

The man in the pink house would seem to be an outlier — totally inexplicable in the greater scope of Earthbound, because no one else suggests that Giygas might be female. However, to advance the plot, Ness and Paula need to head to the Threed hotel. Standing outside it, seemingly waiting for them, is a blonde woman who appears to be wearing a black bikini (or a black bra and panties). Because I’m the type of RPG player who talks to everyone in town, I immediately assumed that this woman was the person both the NPCs I mentioned were describing: a suspicious woman who keeps company with zombies but also Giygas in female form. I might be the only person who thought this way, based on the fact that this woman gets relatively little mention in the message boards and social media posts of fans going deep on Earthbound lore.

Whoever she is, she leads Ness and Paula deep into the hotel, to a room that, upon them entering, turns out to be full of zombies and ghouls who immediately pounce on our heroes. Fade to black.

Via this playthrough on Youtube.

According to the Earthbound wiki, this mysterious woman shows up later, on the beach of the resort town Summers, where she’ll ask Ness not to bother her if he tries to strike up a conversation. I’m not sure this is the same woman, even if the sprite is identical; the one in Summers could just be a vain beach babe. Let’s assume they’re not the same woman. In that case, the one in Threed is decidedly allied with the bad guys. She also never shows up again once she successfully lures Ness and Paula into her trap in the hotel, so there’s never any clarity on why she’s working with zombies… except for what the man in the pink house tells you, about Giygas being the zombies’ boss of bosses — and that big bad might be, despite what you’ve been led to expect, a woman.

The first time I played through Earthbound, I didn’t even question that this woman truly was supposed to be Giygas, at least until the game progressed and it didn’t further this linkage in any way. The other feminine associations Giygas has didn’t come to my attention until much later, but I’m not sure they’re all supposed to add up to a specific conclusion. But then again, if they don’t, who are we supposed to assume the woman in the black bikini is supposed to be and why is she in league with the zombies?

The mind boggles, and as much energy as Earthbound fans have put into the Giygas abortion theory, I’d love for them to put some effort into who this zombie groupie is supposed to be.

The Monsters You Can’t See

Back in early 2023, Nadia Oxford hosted an episode of the Retronauts podcast that explored Stephen King’s connection to video games. Despite being familiar with King’s work and also Earthbound, I’d never really considered how much this game has in common with the It — the novel and either the adaptations. In any of them, the story’s big bad mostly takes the form of Pennywise the clown, but that’s just a projection; the real monster is something that predates human consciousness and comes from somewhere else. Later, it appears to be a giant spider, and when the protagonists see this version apparently laying eggs, they wonder if it might be female. It’s up for debate, I suppose, but the true form might actually be one that’s actively harmful to perceive, to the point that no one who experiences it lives to tell the tale. As a result, the it in It literally defies human understanding. You cannot grasp its true form.

Clearly, Oxford has been batting around the connections between It and Earthbound for a while, as this piece, originally written for USGamer years before the Retronauts episode, points out that both can be reduced down to the one-sentence summary “There’s a pack of weird kids on a journey to save the world.” I was genuinely surprised that I’d never made these connections on my own, that this amazing, strange video game I care a lot about has striking parallels to this famous work of horror fiction, to the point that it’s very probable that the latter actually influenced the former.

I point all this out not to prolong an already lengthy piece but instead to reflect on how these similarities should help us think even more highly of Earthbound. Not only did Nintendo put out a good if unconventional RPG, but also it did something that manages to out-weird even peak weird Nintendo when you dig into it. It’s daring to make players engage in a story that uses pixels to approach the cosmic horror of the unknowable. That might sound rather highfalutin, especially for a video game released in the mid-90s that was advertised with a fart scratch-n-sniff, but it’s the questions that don’t have answers that have me still wondering about Earthbound nearly thirty years later. They just make me like this game more.

A thing that’s so beyond human understanding that attempting to know it hurts you. What could be more un-Nintendo than that?

Miscellaneous Notes

I actually have my own personal story about a weird intersection between Earthbound and my subconscious/unconscious. I shared in on Singing Mountain, a VGM podcast I hosted back in the day before my interests in exploring gaming history moved elsewhere — and ultimately arrived at this blog. I call it “Ric Ocasek in Moonside,” and I recorded it as part of VGM+POP, a subseries I was doing about the intersection of pop music and video games. Basically, Earthbound’s game mechanic of collecting melodies that Ness associates with memories came true for me in a way that was so surprising that it verged on spooky.

Have a listen if you want yet another detour to the weirdness of Earthbound.

I really should conclude Singing Mountain in some kind of proper way one day, but for the moment I prefer the kind of stories I can tell on this site.

Speaking of previous creative projects, however, I was very surprised to read Nadia Oxford’s piece on Steven King’s influence on video games and see that she linked to a piece that I wrote on my blog back in 2013: about how there seems to be a connection between The Shining and Super Mario Sunshine. I’m not sure if there is, necessarily, but it’s something on the list of items to re-investigate for this blog. One day.

Going back to Earthbound and all things verbal, I think it’s interesting that the English title of the series is an autoanytonym. Also known as a contranym, it’s a word that means one thing and the opposite, like how cleave can mean both “separate from” and “adhere to,” or how oversight can refer to close attention paid to a given thing or a mistake that resulted from a lack of close attention. Out of context, the word earthbound can either mean “bound to the earth” or “bound for the earth,” in the sense of humans are earthbound in that we’re stuck on the planet but a comet hurtling through space towards earth is also earthbound. I’d be curious to know which sense the localizers — or specifically Lindblom on his own — intended when the name was picked for the North American release.

While the English localization selected Giygas over Geek as the name for the final boss character, it’s worth pointing out that the word geek has darker implications than you might expect, considering how it’s used in contemporary English. The word entered English as American carnival slang, and specifically referred to an act in which a person, acting the part of a “wild man,” would thrill audiences by eating live animals. According to Etymonline, geek goes back to North Sea Germanic and Scandinavian, to an imitative word meaning “to croak, cackle” but also “to mock, cheat.” In 1975, the professional wrestler “Classy” Freddie Blassie released a novelty single, “Pencil Neck Geek,” which played off a catchphrase he used to insult opponents in the ring. As Blassie used the term, it seemed to imply that a supposedly masc-presenting wrestler was actually lacking, but by the 1980s, the term had come to mean in teenager slang more or less what we think of today: a studious person but perhaps one who’s also a little weird, and ultimately the Anthony Michael Hall’s character in the 1984 film Sixteen Candles cemented this meaning in a way that stuck. So no, by the standards of 1995, geek wouldn’t have implied anything scary, but its usage belies a past associated with the freakish and the bizarre.

Playing through Earthbound for the first time, it was Threed that made me realize that the cities Ness travels to early in the game each take their name from the cardinal numbers: Onett is first, Twoson is second, Threed is third and Fourside is fourth. It’s hard to spot the pattern until Threed, however, because just looking at the first two, you wouldn’t necessarily know to pronounce them like the numbers they’re based on. Onett, on its own, could be pronounced “oh-nett,” and Twoson could be pronounced like the city in Arizona. Threed is unmistakable, but even then there’s a little trivia note there. The original name for the city was initially Threek, which is a pretty good pun, giving the zombie horde that’s overrunning the city when you first arrive there. It was switched at some point, however, and the general consensus is that someone realized that it could read as “three K,” and the Ku Klux Klan is already something the English localization had to take pains to disassociate itself from.

Since I don’t know if I’ll circle back to Earthbound in the near future, I wanted to point out that just as the heroes in the first two games have names that reference Nintendo consoles, Ninten in Earthbound Beginnings and Ness in Earthbound, the female leads also have a connection. In Earthbound Origins, the pink-wearing psychic girl is Ana. That name, combined with the name of her counterpart in Earthbound, Paula, gets very close to Pollyanna, which was the title of a song on the Earthbound Beginnings OST that was remade as “Home Sweet Home” in Earthbound and as “A Certain Someone’s Memories” in Mother 3. I think the name Pollyanna is an allusion the 1913 children’s novel of the same name, mostly because the other female party member in Earthbound Origins, Pippi, is clearly a reference to another children’s novel, Pippi Longstocking.

While I said there’s not much written online theorizing on who the mysterious woman in Threed is supposed to be, I was very surprised to find out there’s a very specific theory that one person posted to Reddit a year ago: that she might be a reference to the 1984 movie The Natural. (Spoilers for a forty-year-old movie, I guess?) In the movie, Barbara Hershey plays Harriet Bird, a mysterious woman who while wearing black lures the Robert Redford protagonist to a hotel in order to shoot him. I’ve never seen this movie, and in fact most of what I know about it comes from the Talking Simpsons episode about “Homer at the Bat,” so I can only shrug and say that it’s possible, I suppose. It’s also possibly a coincidence, but it’s not any wilder than anything else I put in this piece.

There’s a more credible theory that Giygas shares some creative DNA with another psychically powered Nintendo villain, Pokemon’s Mewtwo. In Earthbound Origins, the sprite for the final boss does look a bit like the Pokemon character. The English localization for the game calls this character Gigue, not Giygas, and despite some narrative dissonance between the two, they are supposed to be the same character on some level.

Now, the studios that developed Earthbound are Hal Laboratory (which is well known and which still makes Nintendo titles today) and Shigesato Itoi’s company Ape Inc. Shortly after Earthbound’s North American release, however, Ape Inc. became Creatures Inc., which along with Nintendo and Game Freak created and still own the Pokemon franchise. I don’t think anyone has said on the record that a formal connection exists, but the fact that the same company, more or less, made both franchises would seem to indicate it’s a possibility.

Finally, in researching all this, I found out that Umaro in Final Fantasy VI is not my first exposure to the term gigas. Secret of Mana, released in North America one year previous, features three boss characters that are each called by that name: Fire Gigas, Thunder Gigas and Frost Gigas, the last of which is actually Santa Claus. (Surprise!) They do look like nasty giants, however. I suppose that the term found its way into the game because both it and Final Fantasy VI were localized by Ted Woolsey. However, it seems to have been present in the original Japanese, as they’re ファイアギガース (Faiagigāsu), サンダーギガース (Sandāgigāsu) and フロストギガース (Furosutogigāsu).