What’s With the Equals Signs in Golden Axe?

A fair warning: For this post, I’m taking the thrilling world of Conan the Barbarian–style sword-and-sandal adventures and turning it into a post about… punctuation. I think of this post as the second in a series beginning with the one about Blanka’s name: a thing that confounded me when I was spending time in arcades as a kid and just watching attract modes play on a loop. Decades later, I have an explanation for what I was looking at, and I’m betting I’m not the only one who was wondering.

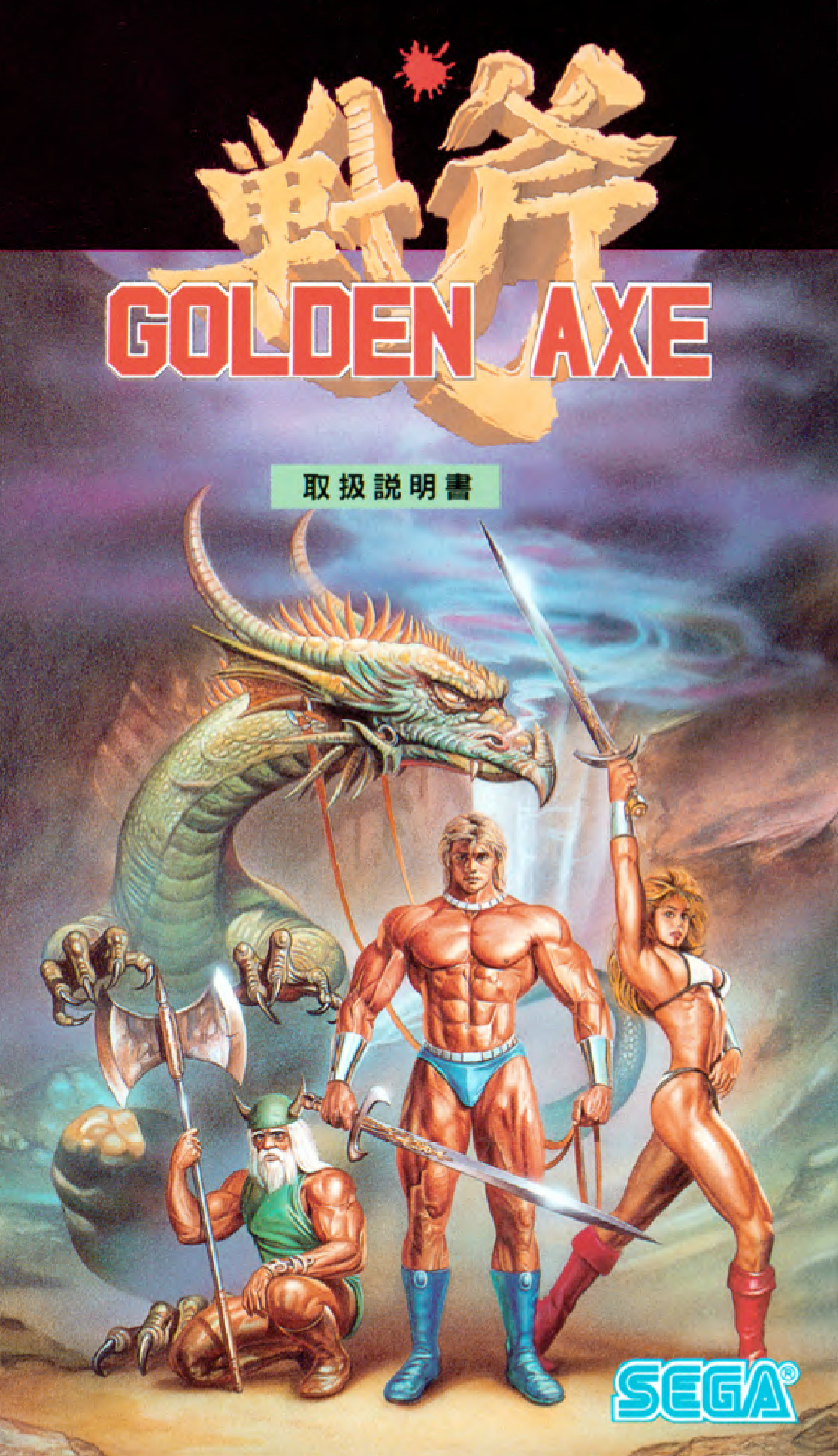

If you were, in fact, in arcades back when Sega’s barbarian brawler Golden Axe stalked the earth, you may have noticed the unusual way the four main characters were introduced in the attract mode. These screens display identically in the English and Japanese versions of the game, BTW.

For example, the main hero is named Ax Battler. (And yes, that is a strange choice for a name, as I explain in the miscellaneous notes section.) The way his screen introduces him with that equals sign, however, you might conclude that his name is Ax, with Battler perhaps being his class: “Ax = Battler,” if you will, or “Ax is a Battler.” But no, immediately below this line is “The Barbarian,” which seems to reframe him as something else.

The next screen introduces Tyris Flare in a similar way, although at least I don’t think anyone would mistake Flare for her class. She’s an amazon who has flair, sure, but the intro screen is specifying flare, which is perhaps significant because all her magic attacks are fire-based. Hmm…

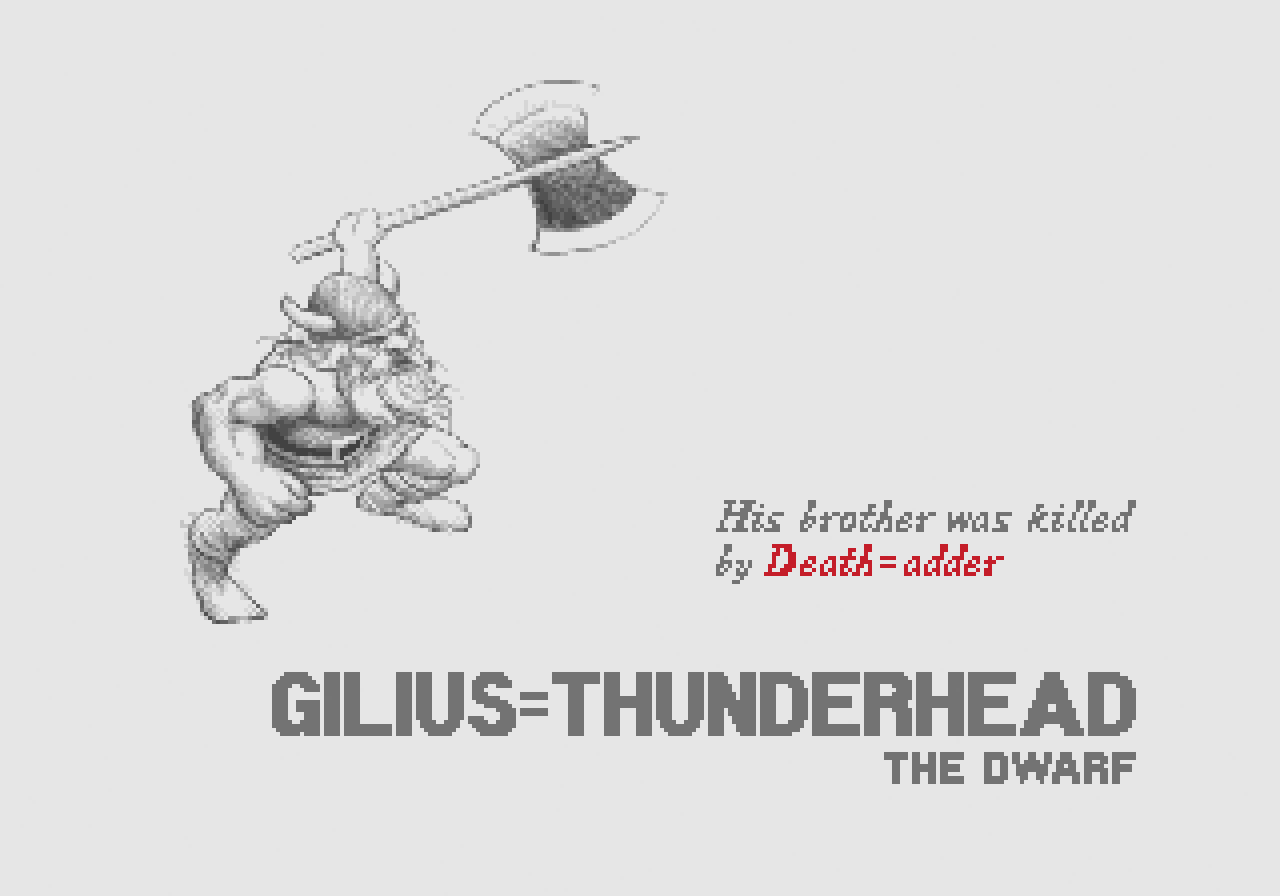

And your personal mileage may vary with ol’ Gilius Thunderhead, though surely Thunderhead would be the kind of class you’d have to level up to and not start the game as. No notes on this name, honestly. It’s badass.

Finally, you’ve got the big leather daddy villain, Death Adder, which my childhood brain read as “the guy who adds to death,” because I grew up in North America where we don’t generally call snakes adders. They do exist over here; the Eastern hognose snake is sometimes known as the spreading adder, for example, but it’s just not a common term. I am sure I’d never encountered it before Golden Axe.

So yeah, to restate the scene: I’m a little kid in an arcade, fairly ignorant of the world and trying to make sense of a bunch of words that don’t seem like they’re used in a way I’m familiar with. I just plunked in a quarter and got going on bashing bad guys, but the whole thing made me feel like that Simpsons joke with Lisa and the Yahoo Serious film festival: “I know those words, but that sign doesn’t make any sense.”

The answer, of course, lies in Japanese — specifically, the various ways the written form of this language can demonstrate the break between someone’s first and last names. These are not equals signs but double hyphens, a punctuation mark used differently in English and Japanese and rarely used in either.

In English, the double hyphen shows that a divided word is actually meant to be hyphenated and is not merely hyphenated as a result of landing on a line break. The example the Wikipedia page gives is cross⸗country, where cross⸗ lands at the end of one line and country at the beginning of the next, to show you that it’s meant to be cross-country and not crosscountry. Often, the lines of the double hyphen are made at an angle specifically so a reader doesn’t confuse the mark with an equals sign. (Sega was not informed of this rule, it seems.)

The double hyphen is sometimes used in stylized branding as well, probably most notably with the Waldorf Astoria hotel, which I explain in the miscellaneous notes section. (Image via Wiki Commons.)

In Japanese, the double hyphen (ダブルハイフン, daburu haifun) is one of the symbols used to separate first and last names being written in katakana. For example, my name is Drew Mackie. I could write it in katakana as ドゥルー・マッキー, with the dot in the middle representing the separation between my first and last names. You’ll occasionally see the double hyphen doing that same thing, but it’s rarer and when you do see it, it’s more often representing a western name that is already hyphenated. For example, Catherine Zeta-Jones’s name could be written as キャサリン・ゼタ=ジョーンズ, with the dot representing the space and the double hyphen linking together her two last names. And Jean-Claude Van Damme’s name would be ジャン=クロード・ヴァン・ダム. Occasionally the double hyphen can represent other internal punctuation. For example, the Japanese League of Legends page renders the name of the enemy character Kha’zix as カ=ジックス, with the double hyphen representing the apostrophe.

I presume this symbol fell into fashion in written Japanese for the same reason I have found that em dashes are not helpful in discussing Japanese in translation: Single horizontal lines can be easily mistaken for the chōonpu, the ー symbol that tells the reader that the vowel sound should be long. Whatever you can do to differentiate these symbols will help the reader understand what you’re trying to communicate.

And that’s it, really. It’s not a great mystery, but years after the fact I was gratified to find out that what looks like equals signs in Golden Axe was actually just a double hyphen showing the break between first and last names. These marks likely persisted in the localized version of the game because Sega didn’t think it was worth the effort to change them. “It’s fine. Little English-speaking kids can figure it out,” is what I imagine the Sega guys in charge saying. And they were right; it just took a few decades for this one to make the connection.

In the context of the Golden Axe attract mode specifically, I do wonder why Sega might have used this symbol instead of the dot (or bullet, if we’re getting technical about typography). If there was a shift in Japanese culture away from the former and toward the latter, I couldn’t find any information about that online. For what it’s worth, the bullet point is a lot less likely to be confused by westerners like me, but I doubt that would be motivation enough to make the change.

Via VGJunk.

Miscellaneous Notes

Sega’s decision to name its hero Ax Battler (アックス=バトラー, or Akkusu Batorā) is a confounding one for several reasons, the foremost being that Ax Battler wields a sword. So Ax Battler is actually a sword battler. It’s also weird that the game series is Golden Axe — spelling it axe and not ax, though both are valid in English — but the hero spells it the other way. This is odd enough, but it’s further complicated by the fact in 1991 Sega released a Game Gear spinoff in the style of Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. That game’s title is Ax Battler: A Legend of Golden Axe, meaning it had to put both spellings of the word in the same logo.

The Japanese release suffers from the same problem. Over there, it’s アックスバトラー ゴールデンアックス伝説, or Ax Battler: Golden Axe Densetsu. The English text also uses both spellings of the name even, which means the localizers looked at that, saw the visual dissonance of Ax an Axe and said, “Okay, sure, why not in English too?”

Perhaps Sega realized this was a clunker of a name? In 1994, Sega released a one-on-one fighting game sequel, Golden Axe: The Duel, featuring descendants of Tyris Flare and Gilius Thunderhead named Milan Flare and Gillius Rockhead. The analogue for Ax Battler does not bear the family name, however. He’s Kain Blade. Not only does his backstory not mention the original hero, but also he would seem to namecheck two other sword-wielding Golden Axe heroes: Kain Grinder from Golden Axe III and Sternblade from Golden Axe: The Revenge of Death Adder. The 2008 reboot, Golden Axe: Beast Rider, focuses on Tyris, though she can encounter an NPC named Tarik the Axe Battler, which not only fixes the spelling of “axe” to match the series title but also makes his original name a description of what he does. Essentially, it’s treating the character the way I thought the attract mode was back in the day.

Until researching Golden Axe in Japanese, I did not realize that many of the bad guys in the game take their names from liquor brands. Heninger, a mace-wielding bad guy, seems to be named after the German brewery. The very suggestively named Longmoan — the guys swinging clubs — are probably a reference to Scotland’s Longmorn distillery. And the hatchet-wielding amazon Zubroka enemies are variously known by different names depending on their color: Storchinaya is purple, Syrobaya is green, Lemanaya is red and Gruziya is black. Three of those names correspond to brands of vodka — Żubrówka, Stolichnaya, and Stolovaya. And based on this L.A. Times grocery store grocery ad from 1996, Lemanaya is apparently a lemon-flavored variety of Stoli that was marketed in the U.S. at one point but may not be anymore. And the bald, Abobo-looking dudes are the Bad Brothers, which is probably a reference to Budweiser (in Japanese, バドワイザー or Badowaizā), a fact that seems to be supported by the fact that the navy blue, powered-up versions are named Sgt. Malt and Sgt. Hop.

The Japanese name for the bird-beaked “Chicken Leg” steeds that serve as the series mascots, however? It’s just チキンレッグ, or Chikin Reggu — the same we call them in English. I could have sworn there was some usage of the term Bizzarians for these creatures, but it’s seemingly only used now on the TV Tropes page for the series.

The double hyphen is also used to mark morpheme boundaries when writing out the language of the Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan.

The word adder has nothing to do with math, in case you were wondering. It comes to English via the same process that turned napron into apron, ekename into nickname and narancia into orange. What used to be “a nadder” became “an adder” due to faulty separation between the noun and the accompanying indefinite article.

Outside of the specific context of double hyphens telling the reader that yes, this word *is* supposed to be hyphenated, the double hyphen was sometimes used in stylized brand names. For example, New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel initially hyphenated its name and sometimes did so with a double hyphen. This 1933 ad for it features a fancy-looking one.

When Conrad Hilton purchased the hotel in 1949, the sign was swapped for a double hyphen in all branded contexts — to evoke the hallway linking the Waldorf and Astoria buildings that comprised two original parts of the hotel in its original form, but also to recall the importance of the hotel to New York society, which for a period nicknamed it “The Hyphen.” The double hyphen, in this context, literally underscores that legacy, even if it doesn’t follow the typographical rules. The hotel discontinued the use of the double hyphen in 2009.

And while the text displays the same in the English and Japanese versions of the game, there is a major difference in regions: In Japan, there is a flashy scene of gore that’s missing from the U.S. version and which certainly would have gotten my attention as a kid.

If only.

In closing, I’d just like to point out that whoever designed this Golden Axe art took special care to give Ax Battler a visible penis line in his speedo, and we can all be thankful for this.