The Many Mysteries of Castlevania’s Sypha Belnades

This being the first post going up in the spooky month, I am obligated to talk about Castlevania. However, because it’s me, I’m using Castlevania as a lure to get you to read a post that’s actually about linguistics, which is a fun Halloween prank if there ever was one.

Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest shares a special bond with Super Mario Bros. 2 and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link in that each of the games responded to the success of the first installment in their respective series by being experimental and weird in a way that alienated a lot of fans. So when Konami released a third Castlevania game — Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse in the U.S. and Akumajō Densetsu, “Legend of the Evil Demon Castle,” in Japan — it returned to form in many ways, even if it doesn’t star Simon Belmont, the whip-flinger from the first two games. In his place is Trevor Belmont, Simon’s ancestor and the first of the Belmont line to take on Dracula.

Trevor is not alone in his quest, however. He’s joined by the thief and pirate Grant Danasty, Dracula’s son Alucard, and the sorcerer Sypha Belnades, a character initially shrouded in mystery, and who still carries some of the mystery with her all these years later. One of the chief reasons she has this air about her, even today, is that Castlevania III attempts to obscure the fact that she is a woman.

In both the Japanese and English versions of the game, her official character art has her hood and bangs covering her face to the point that you can’t really see what she looks like. And in the Japanese version of the instruction manual, her bio does not gender her, though it’s not clear whether this results from Konami setting up a Metroid-style gender surprise or not, as Japanese just doesn’t use pronouns as often as other languages.

Translated (but in a way that kinda sorta preserves the fact that the text does not gender Sypha): “Rumors of their death circulated within the Eastern Orthodox Church, but they had been captured by the boss at the end of the forest, the Cyclopes. Sypha, like Ralph, is a vampire hunter. They usually attack with a holy staff and have the same speed and jumping power as Ralph. Their attacks include fire, freezing, and lighting bolts that are quite powerful and can be used for ranged attacks. However, their armor is weak, so they take heavy damage from enemies. Settling battles quickly is the key to victory.”

Let’s say that Konami was using the Japanese language’s relative lack of pronouns to make a surprise out of the revelation that Sypha is a woman. That’s much harder to replicate in English, which uses pronouns a lot — and often gendered ones at that. It wouldn’t have been standard practice at the time to refer to this character as they/them, but also it would have read oddly to just not use pronouns at all, to the point that it might have signaled that the writing was making an extra effort to withhold her gender. As a result, whoever translated the instruction manual text just decided to assign Sypha masculine pronouns. I’m assuming this was done because it was the best way to preserve the surprise at the end of the game, though I suppose it’s also technically possible they were not informed of Sypha’s gender, especially if they were working from the Japanese manual without playing the game as a primary reference.

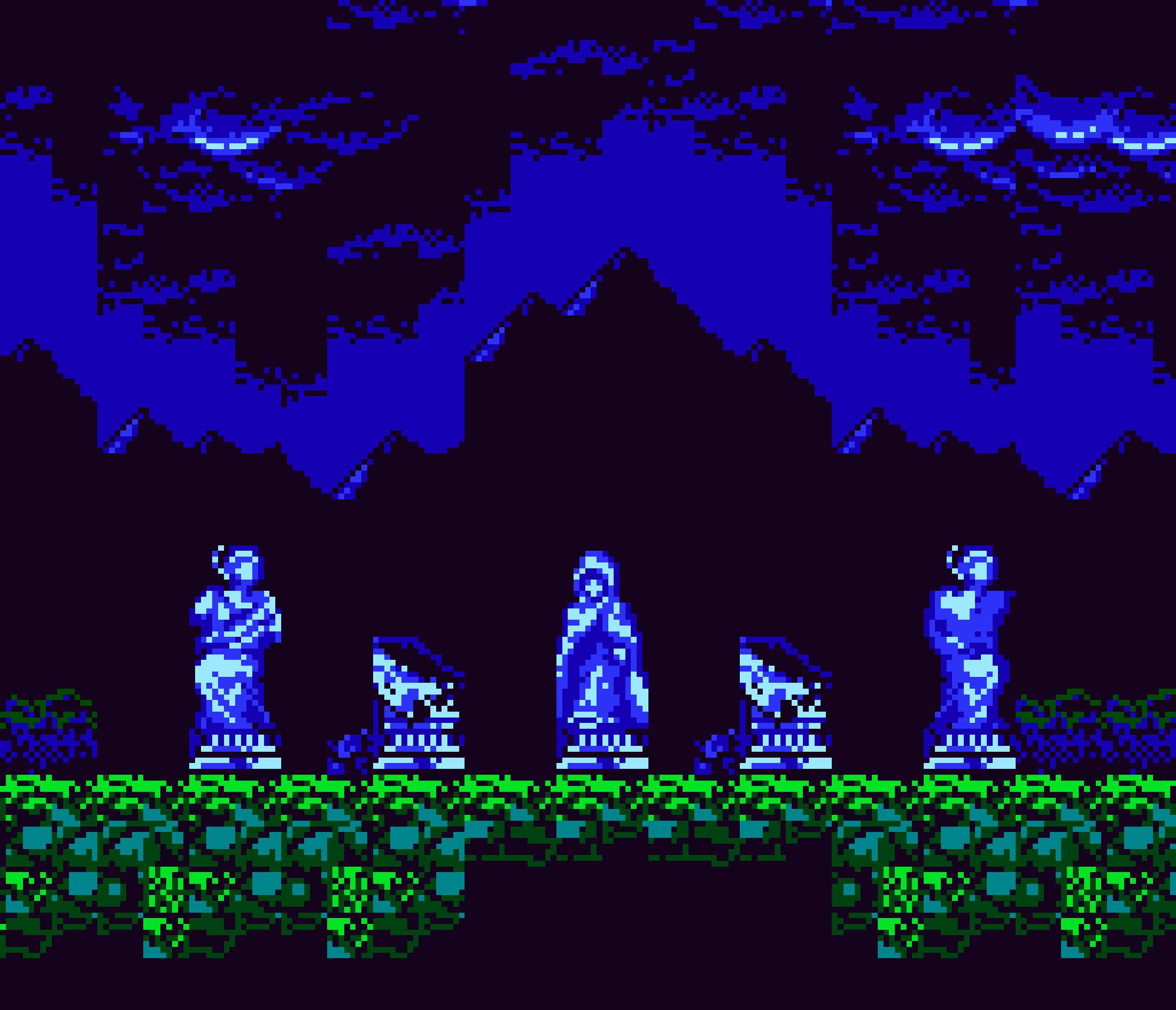

Pronouns factor into the actual game as well. Trevor first encounters Sypha in the Forest of Darkness, where a cyclops boss has turned her into a statue. Upon killing the cyclops, Sypha becomes human again, and the player is given the option to add her to the roster of controllable characters. In the Japanese version of the game, the player is given options that answer obliquely, without any pronouns: “つれていく” (or “Take [them] with you”) and “つれていかない” (or “Don’t take [them] with you”).

The English version not only features pronouns but masculine ones — again, I assume because Konami wants to set the player up for a surprise, because “take with you” and “leave behind” would have worked just as well.

Should you defeat Dracula with Sypha as your ride-along, the ending of the game shows her and Trevor standing side by side on a cliff, watching as the villain’s castle crumbles. Sypha removes her hood, revealing a head of long blond hair, and then Trevor puts his arm around her. This might be a “they gay?” moment, honestly, as Trevor also has long hair and there’s still not much in these pixels to suggest Sypha’s gender. But text flashes on screen to make the situation perfectly clear, perfectly hetero.

In the Japanese version, we’re told the following: “Due to her cruel destiny, Sypha was raised as a vampire hunter and lived hiding her true identity. It wasn’t until she met [Trevor] did she start to feel at ease. [Trevor] also has mutual feelings for her.” (In the Japanese version of the game, Trevor’s name is actually Ralph. More on that in the miscellaneous notes section.)

The American version misspells Sypha’s name but finally uses female pronouns. Instead of Sypha no longer hiding her true identity, it simply says, “Syfa, the Vampire Killer, has had a bad life, but since she met Trevor she is beginning to feel more comfortable with herself.” It’s actually a sweet, “you don’t have to hide who you are” ending to Sypha’s journey no matter which translation you’re using.

It’s not said explicitly in the game, but according to the greater series lore, Sypha has children with Trevor, meaning that she is likely a forebearer to the original Castlevania hero, Simon. I say “likely” because I suppose it’s possible that Trevor could have had children with someone else, but later games introduce members of Sypha’s family line that do not appear to be blood relatives to the Belmonts. Most notably, there’s Yoko Belnades in Aria of Sorrow and Dawn of Sorrow. She’s a magic user who wields a staff and seems to take after her ancestor despite six centuries separating them. And Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin features a hero who is a Belmont descendant with a different last name, Jonathan Morris, who is accompanied in his quest by the sorceress Charlotte Aulin. In a profile on the game in Nintendo Power, Castlevania producer Kojji Igarashi says that Charlotte is, in fact, a relative of Sypha’s, though he does so with a different family name: Fernandez.

As if there wasn’t enough confusion around Sypha already, what’s this business with the Fernandez clan? Is it merely a matter of symmetry, with the hero in Portrait of Ruin being Belmont family-adjacent but somehow less than a full-fledged member with a different last name? That may be a factor, but the matter goes deeper than just that.

As near as I can tell, the first time the Fernandez family shows up in an official capacity in a Castlevania game is the 1999 title released for the Nintendo 64, nicknamed Castlevania 64 in the west and released in Japan as Akumajō Dracula: Mokushiroku, “Demon Castle Dracula: Apocalypse.” The Belmont descendant protagonist in this game is Reinhardt Schneider, and his spellcasting player two is twelve-year-old Carrie Fernandez, who we are told is of the same family as Sypha.

Translation: “Carrie, a descendant of the Fernandez family, is said to have once fought alongside the warriors of the Belmont family. She awakened her exorcism abilities when she witnessed the death of her adoptive mother. Years later, sensing the imminent return of the Demon King, Carrie sets out for the Demon Castle to seal off Count Dracula using her exorcism.”

I’ve only seen Carrie’s name rendered in Japanese materials for the game in katakana, which would imply that Fernandez is specific to the western localization of the game. But if her last name uses the same katakana as Sypha’s, ヴェルナンデス, why isn’t she just Carrie Belnades?

Well, according to the translators I work with on this project, it’s strange that either side of this magic family wasn’t Velnandes from the get-go, as the initial character in Sypha’s last name, ヴ, represents the “v” sound, which is not native to Japanese. That character is there from the start, even in the Japanese instruction manual for Castlevania III. In fact, in the ending to that game — in English *and* Japanese — she’s identified as Syfa Velnumdez, which is a whole different name but at least one that matches how Fatimah and Anne are translating the character’s name.

EDIT: After going live, I realized that Konami did use the spelling Velnandes in official materials, though curiously it’s only for Castlevania Judgment, the 2008 fighting game spin off that features Sypha as a playable character.

And as near as I can tell, that’s it.

I don’t know who made the call to localize Sypha’s name as Belnades or Carrie’s as Fernandez, but the fact that this is what made it into the final version of any Castlevania game allows me to talk about an issue I’ve encountered living California and interfacing between English and Spanish. Yes, here is where I get to indulge another facet of my nerdiness that’s even nerdier than video game history: linguistics.

Certain sounds tend to do-si-do quite a bit when you’re moving from one language to another, and the permutations of Sypha’s surname show off one set of them. These sounds include the following:

[b], the initial sound in bag

[p], the initial sound in pond

[v], the initial sound in vase

and [f] the initial sound in four

Depending on your language background, you may be looking at these and thinking they have about as much in common as any consonant sounds do, but they’re actually closely linked. First, [b] is the voiced version of [p]; the process your body does to make these sounds is identical, save for with [b] you use your vocal cords and for [p] you don’t. Same thing for [v] and [f]. They’re very similar, and this is one reason these letters switch around a lot. For example, compare ball and its Spanish counterpart, pelota. And while we’re at it, compare pelota and the English word pellet. Even staying within English, it’s interesting that we pluralize knife, elf and leaf as knives, elves and leaves. Without thinking about how [f] and [v] are similar, English-speakers just kind of intuit that [f] and [v] can be interchangeable, at least in certain instances.

Second, all these sounds are created with the same part of your mouth real estate, so to speak. The [b] and [p] noises are made by putting your lips together, and the [v] and [f] noises are made by putting your bottom lip against your teeth. That puts them in super close proximity, especially considering where other noises are made — the [k] in clock and key comes from all the way at the back of your mouth, for example. To massively simplify the whole thing, they are essentially mouth neighbors, and they therefore swap with each other, especially when you’re moving from one language to another.

Compare the English word fin, as in the things you’d find on a fish, to the first syllable in pinniped, a fancy word for seals that translated from Latin literally means “fin-footed.” You can see how these syllables are related, even with [f] at the start of one and [p] at the start of another. BTW, that last syllable in pinniped is clearly related to the English word foot — and yes [d] and [t] are another voiced and unvoiced pair. English-speakers learning Spanish may be surprised by the pronunciation of one of the most basic vocabulary words: veinte, “twenty,” because it’s pronounced with what sounds a lot like the English [b] noise. It’s not exactly that; Spanish has two similar phonemes, [b] and [β], both of which can be represented in written language with both “b” and “v,” which just goes to show that separation between these two phonemes can be quite small, depending on who’s doing the speaking. And it’s easier than it might initially seem for a [b] to turn into an [f] and then turn into a [v], as we see with all the permutations of Sypha’s last name.

I hope this helps explain to a degree how different translators looked at that name ヴェルナンデス and interpreted it so differently. Depending on what language background that person was coming from, they’re not as far apart as you might think.

Konami seems to have more or less ended the Fernandez line — or at least has consolidated them under the Belnades name to avoid further confusion. I do wonder if the Nintendo Power article on Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin references Carrie’s family line instead of Sypha’s because Carrie debuted in a game made specifically for the Nintendo 64, and therefore Nintendo had an interest in emphasizing that connection over one to a Belnades on any other system. In any case, the games Carrie appears in are now relegated to an alternate continuity outside of the canonical one. Perhaps they’re all Fernandezes over there in that continuity.

Personally, I love how convoluted Sypha’s story is, not just within the confines of Castlevania III but also moving forward, as Konami positioned her as this matriarch of this family of magic users and a female line that serves as a counterpart to the Belmonts. It’s a mess, but it’s a rich, fertile mess, and whether you’re someone tasked with localizing a Castlevania game or a player just trying to make sense of the expanded Castlevania universe, there’s just a lot to work with. On some level, it makes sense that this character isn’t bound by rules of language or convention or genetics or anything, because she’s the mother of magic, and she gets to break the rules.

And it’s for these reasons that I’m especially amused that one of her long-lasting legacies is her appearance in Captain N: The Game Master. The show made liberal use of Castlevania in its first season, and then in its third and final season, the episode “Return to Castlevania” tried to see what it could make of Castlevania III. The result is about as weird as you’d expect, with Alucard becoming a stereotypically radical/badical early ‘‘‘ ’90s teen.

What’s really interesting about the episode is that it features an ally for our heroes who comes from the Castlevania world — a grandfatherly wizard who wields a staff. Though unnamed in the episode, it really does seem like this is supposed to be the Captain N version of Sypha, if filtered through the imagination of someone who read the instruction manual without playing though the game and was like “Sure, it’s some old wizard dude. I can write that.”

Simon Belmont, meet your… great-great-great-grandmother?

Not that many video game characters get to be that *and* also the mother of an entire genealogy of heroes. What a fun bit of confusion.

Miscellaneous Notes

Some people read Sypha’s first name as a play on the word cipher, which can mean “nonentity” or “a concealed message.” This is entirely possible, as the katakana for both cipher and Sypha could be the same: サイファ, saifa. I’m not sure it’s intentional, honestly. A lot of places I see positing this seem to also imply that cipher means “mystery” or “enigma,” which would be more fitting to Sypha’s character. But that’s not quite what the term means, according to the dictionaries I looked it up in. Cipher can also just mean “zero,” and both cipher and zero trace back to the Arabic sifr, meaning “zero” or “empty, nothing,” which is perhaps not an appropriate connotation for a character who has so much going on.

A minor character in Castlevania 64 and its sequel is Camilla Fernandez. Not to be confused with the recurring vampire enemy Carmilla, whose name sometimes also gets translated as Camilla, she is Carrie’s relative who has been turned into a vampire and whom Carrie must fight. At one point in the game, the character was supposed to be the reanimated corpse of Sypha herself, which raises the interesting point of whether they would have called her Sypha Fernandez in this game. For what it’s worth Symphony of the Night already had featured a fight with a reanimated Sypha.

As the Legends of Localization page on Sypha notes, Nintendo Power’s rendition of her seems to be drawn to preserve the mystery of the character’s gender. The article refers to her using male pronouns, for what it’s worth.

In Japan, Trevor’s name is given as Ralph C. Belmont: ラルフ・C・ベルモンド, or Rarufu Shī Berumondo. You may be wondering what the middle initial stands for, and you are not alone. Konami has never said officially. However, an anonymous developer who worked with Castlevania creator Hitoshi Akamatsu has tweeted about things Akamatsu told them back in the day, and those tweets have been preserved and translated over at Schmupulations. One of them gives the character’s middle name as Christopher but also notes, “As for confusion with the timelines, that’s probably because different teams were making these games. I wasn’t working there when Castlevania Adventure was released.” The reference here is to the Christopher Belmont character in the Game Boy games Castlevania: The Adventure and Castlevania II: Belmont’s Revenge. They’re not the same guy, however; the series timeline puts him as living a hundred years after Trevor but still before Simon.

For what it’s worth, the Castlevania III end credits also give Trevor the same middle initial.

The katakana for the main family’s last name could also be translated as Belmondo instead of Belmont. In fact, the end credits to the original western localization of Castlevania identify the hero as Simon Belmondo, though the official western version of the name has been Belmont from Castlevania II onwards. I suppose that’s a choice, giving the hero a last name that means “beautiful mountain” over one that means “beautiful world,” but there is a persistent rumor given that the central family was named after the French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo. It’s noted on this site that the 1982 action comedy Ace of Aces was particularly popular in Japan, but the text seems… well, Google Translated, and I still can’t find any proof linking this actor to the Konami series.

If you’re interested, I also have a follow-up post where I explore the joke credits at the end of the original Castlevania here.

Of the playable characters introduced in Castlevania III, Alucard has clearly become the most important character in the series, with Sypha coming in second. The animated Netflix adaptation made them the two co-leads after Trevor, in fact. Entirely missing from that version of the Castlevania story, however, is Grant Danasy, though the showrunners explain that he’s somewhere in this continuity… just not onscreen. The show did offer up an original character who in the final season rounds serves as a fourth to the main trio — Greta, leader of the village Danesti — but according to an interview with the executive producer, she’s not meant to be a stand-in for Grant. She’s just a woman named Greta from a town named after the Dănești region of Wallachia. So there you go.

I’d love to compile a list of “Samus Aran is a woman!”-style surprise gender reveals in video games. I’m not clear if Metroid was the first to do this, but it’s probably the most famous. There’s a debatable one in the Nintendo arcade title Mach Rider, which I should probably cover in a future post and which may or may not be a direct reference to Metroid. And there’s another one in Super Mario Land 3: Wario Land, where the big bad, Captain Syrup, is revealed to be an attractive woman. And in Kid Icarus: Uprising, Dark Lord Gaol is a villain who, once defeated and knocked out of her armor, is revealed to be a beautiful woman. Given the Kid Icarus series’ special relationship to Metroid, I’m almost certain this is a direct nod to Samus.