Is There a John Candy Joke in the Ending to Castlevania?

Pick up any installment of the Castlevania franchise and it will be pretty obvious that these games draw inspiration from gothic horror. All the basic tropes are there: an atmosphere of pervasive dread, the threat of the supernatural, and the notion of humans being helpless to stop the intrusion of the past upon the present, whether literally or figuratively. I mean, the series’ big bad, Dracula himself, embodies all three of these things.

The later you wade into the franchise, however, the more likely you will find an entry that takes itself very seriously. What’s been leached away from the series, from one sequel to the next, is a tongue-in-cheek sense of humor underlying all these gothic horror tropes. In some ways, the first Castlevania game — released for the Famicom on September 26, 1986 — functions as a video game representation of gothic horror but also a pastiche of it, often drawing less so from gothic horror literature than from the movies inspired by those books. Sure, it’s a story about Simon Belmont embarking on a quest to slay Dracula, but along the way he meets a mummy, Frankenstein’s monster, and not *the* Creature from the Black Lagoon but a fishman creature from some body of water — possibly a lagoon, possibly a black one.

This fact is most apparent in the ending to the original Castlevania, which offers up goofy, phony credits that acknowledge where the creative team was getting ideas. I thought I’d go through each screen of them and explain the references. Some are very obvious. Some are rather deep cuts. Some are confounding, even today.

When Simon finally whips Dracula into submission, the scene shifts to a perspective of the vampire’s castle on a cliff. It crumbles, and then we get our credits against a pink morning sky. Right off the bat, in the first pair of credits, “Produced by Konami” is pretty straightforward, but that second one. “Directed by Trans Fishers,” is… well, confusing, for a few reasons.

First off, it reminds me to the salute to the gay steel mill workers at the end of that one episode of The Simpsons, just instead saluting trans people who work in the fishing industry. And you know what? I’m sure they exist and they deserve all due praise. What’s actually going on here, however, is that the game is referencing Terence Fisher, the British director who helmed Dracula — but that would be the 1958 Hammer Films versions of Dracula, starring Christopher Lee, and not the 1931 American adaptation starring Bela Lugosi. This is an interesting point to consider, because being American, I see Dracula and Frankenstein and I alway presume they’re the Universal Pictures takes on the characters, but I’m not sure that’s the case here, as the credits point toward a mix of Hammer and Universal.

So is “Trans Fishers” a mistranslation? Well, there was a tradition in video games back in the day to roll pseudonymous credits to hide the true identities of the people involved in the production in order to prevent these people being poached by rival companies. And while that may be the case with the first few credits, which somewhat correspond to real-life people working on the Konami team, it seems like the later credits, which don’t correspond to Konami staffers, are just taking this funny pseudonym trend and letting it get sillier. For example, it’s not clear whether Trans Fishers is meant to be a stand-in for the game’s actual director, Hitoshi Akamatsu, but it is pretty obviously part of the effort to put Castlevania squarely in the tradition of gothic horror films.

EDIT: Since posting this, it’s been pointed out to me that Konami probably go the first name from Transylvania, which I’m inclined to agree with.

Slide two: “Screenplay by Vram Stoker / Music by James Banana.” Again, the first one is very obviously a nod to Bram Stoker, author of the novel Dracula, with a little of the [b]/[v] confusion I mentioned in my piece on Sypha’s name. Interestingly, the person who best fits the title of screenwriter for the first Castlevania is again Hitoshi Akamatsu, so I’m guessing the credits are all purely horror references and not stand-ins for actual people.

James Banana is presumably a reference to James Bernard, Hammer Films composer and specifically the person who scored the 1958 Dracula. The music for the first Castlevania game was composed by Kinuyo Yamashita and Satoe Terashima. For whatever reason, the name has stuck to Yamashita specifically, even though it’s Terashima who wrote the iconic track “Vampire Killer.”

From here we get into a cast breakdown, with all the major players in the game being assigned to joke versions of real-life horror actors. First up is the actor allegedly playing Dracula: Christopher Bee, a very obvious reference to Christopher Lee. Of all the names appearing in the credits, Christopher Bee is the only one to reappear in any sort of Castlevania continuity: the 1987 “choose your own adventure”-style book The Devil Castle Dracula: The Battle of the Old Castle, which is about Simon Belmont’s descendant, an actor also named Simon Belmont, encountering Dracula on the set of a movie based on the events of the first Castlevania game.

Death, a Grim Reaper boss fought in the game, is credited as Belo Lugosi and Frankenstein’s monster is Boris Karloffice, two very sweaty puns on the names of two fo the major stars of the Universal horror films, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff.

Next is the mummy boss, credited to Love Chaney Jr. — another obvious reference, this time to Universal horror icon Lon Chaney Jr. The actor credited as playing Medusa is a bit of a deeper cut: Barber Sherry. This confused me for a long time, because I couldn't figure out what real-life person was being referenced here. And although I know the answer, I’ll give a spoiler warning in case you’ve always wanted to watch the 1864 Hammer horror film The Gorgon.

Figuring the first name might be a mistranslation of “Barbara,” I ended up on the fact that Bette Davis’s daughter was at one point named Barbara Sherry, but this credit didn’t seem like a weird dig on Bette Davis to me — though I must point out that if she ever played Medusa, she would have slayed. It was only watching TCM one night during the Halloween season that I finally put it together: It’s Barbara Shelley, the British actress who starred in several horror films but most notably 1964’s The Gorgon, which was also directed by Terence Fisher. The fact that she plays the titular monster is something of a spoiler; we find out in the end, even if it doesn’t make a lot of sense, that this British woman who works as assistant to a brain scientist in a central European village is also somehow a snake-haired monster from Greek mythology, who in this version is named Megaera and not Medusa.

Barbara Shelley (not Barber Sherry) as the woman who didn’t realize she was the Gorgon (not named Medusa).

It’s… not a great film, honestly, especially because I’m still not clear if the doctor’s assistant realized she was the monster and whether she was mental timeshare in the style of Glory from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. However, it is interesting to compare the Hammer horror films to the Universal ones that preceded them because the latter offered audiences an iconic female monster that the former never did. Hammer’s first horror movie was 1955’s The Quatermass Xperiment, and by 1964 they’d offered their first female big bad in The Gorgon. (The Brides of Dracula, which came out in 1960, features more than one female bloodsucker but none of them are the main villain, despite what the title might make you expect.) Universal’s horror major movies never really did that. The closest they came was 1935’s The Bride of Frankenstein, but in that movie the bride character isn’t the main villain. (And if you interpret the title literally, it’s referring to Elizabeth, the non-reanimated woman who marries the doctor who makes the monsters.) Weirdly, no Castlevania game has ever featured a monster inspired by the Bride of Frankenstein.

While Medusa would be a recurring enemy character in the Castlevania games, Castlevania II introduces Carmilla, who would become a more iconic female villain of the series, whether in her original incarnation as a floating mask or as a more humanoid female vampire in other games. Considering the relative lack of female big bads — in the Castlevania games and in movies that inspire them — it’s especially interesting to note that Carmilla comes from Sheridan Le Fanu’s lesbian vampire novel Carmilla, published twenty-six years before Bram Stoker published Dracula and generally agreed to been an inspiration for Dracula. Only in 1970 did Hammer explore Carmilla’s story with The Vampire Lovers.

The next slide credits the giant bat boss as Mix Schrecks, a reference to Max Shreck, who played the Dracula knockoff in 1922’s Nosferatu. And as the “flea men” hunchback enemy is credited to Love Chaney, a reference to Lon Chaney, the star of silent horror films including 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Next is probably the most confusing slide, crediting the Creature from the Black Lagoon-style enemy to the actor Green Stranger and the animated suit of armor enemy to Cafebar Read. The internet has concluded that Green Stranger is most likely Glenn Strange, who played Frankenstein’s monster in 1944’s House of Frankenstein, 1945’s House of Dracula and 1948’s Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein, though I’m not necessarily sure that’s what he would be best remembered for, since he also appeared in a lot of Westerns and in 245 episodes of Gunsmoke. He never played a mermonster, as near as I can tell.

And then there’s Cafebar Read, who a lot of people have concluded must be Oliver Reed, a very famous actor who won an Oscar for his role in 1968’s Oliver! but who also did appear in several Hammer films. His most notable Hammer role is 1961’s The Curse of the Werewolf, where he plays an eighteenth-century Spanish man who is, in fact, a werewolf. It’s notable because it was directed by Terence Fisher and not because it makes much sense to link him with a living suit of armor. And if the previous one truly is a reference to Glenn Strange, then we’re at a point in these credits where Konami is just plucking random names from the horror canon, without much thought to tying the actor to a role they made famous onscreen.

So why “Cafebar”? That’s a really good question. My first instinct is to guess that it could be a joke about Oliver Reed’s infamous alcoholism, but I’m not sure that interpretation makes much sense. In Japanese, Oliver would be オリバー or Oribā, and the katakana for bar would be バー or bā. And yes, this is another instance of [b]/[v] flexibility along the lines of the Belnades/Velnandes ambiguity I wrote about in the Sypha article, but it’s also not that much more of a ridiculous substitution than James Banana standing in for James Bernard, I guess. Still, something about this one strikes me as weird, and if you have any better theories for how they got from Oliver to Cafebar, I’m all ears.

The next slide credits the role of the skeleton enemy to Andre Moral, who is almost certainly a reference to the British actor Andre Morell, who appeared in several Hammer films. And in case you thought this slide was going to be easy, it also credits the zombie enemy as Jone Candies, which is another weird one. Any child of the ’80s would see that and immediately presume it’s John Candy, not that it would make any sense in this context, because Candy comes from the wrong era of filmmaking and isn’t a horror icon like literally everyone else referenced. And it’s certainly not any kind of eerie premonition of Candy’s untimely death, especially considering that this game came out eight years before he died.

It’s much more likely that the reference is instead to John Carradine, who played Dracula in the Universal horror films House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula. He’s also the patriarch of the Carradine acting family, which includes Kill Bill himself, David Carradine. Like with Cafebar Read, this joke name is just a few steps beyond the others and certainly more of a stretch than Andre Moral. Carradine’s name would be rendered in katakana as something like キャラダイン (Kyaradain), so his name would have been altered more than most other real-life people namechecked in the credits. But that’s the best guess anyone seems to have come up with.

There is one more theory as to what Jone Candies might be referencing, and although it is only this one site. I’m not sure I think it’s a plausible theory, it is weird enough that I am going to share it anyway. Candy Jones was a fashion model who claims to have been a part of the CIA’s MK-Ultra project, which aimed to identity drugs and other means by which the U.S. government could brainwash people, engage in psychological torture or otherwise control people’s minds. It’s a fascinating rabbit hole to fall though, if you have the time, but one that seems wholly out of step with the vibe of Castlevania.

Finally, the role of the game’s hero is credited to Simon Belmondo. This name is most likely a mistranslation or at least a localization that happened before Koniami finalized the English version of the central Castlevania family as the Belmonts. However, the katakana for the family name is ベルモンド (Berumondo), so it’s not inaccurate so much as it is not the decided-upon localization. If anything, the fact that Belmondo made it into the final version of the game, after a whole list of joke credits that reference real-life actors and movie creatives, makes it seem a lot more likely that Castlevania’s central family truly is named after the French actor Jean-Paul Belmondo, even if Belmondo did not act in horror movies — Universal, Hammer or otherwise.

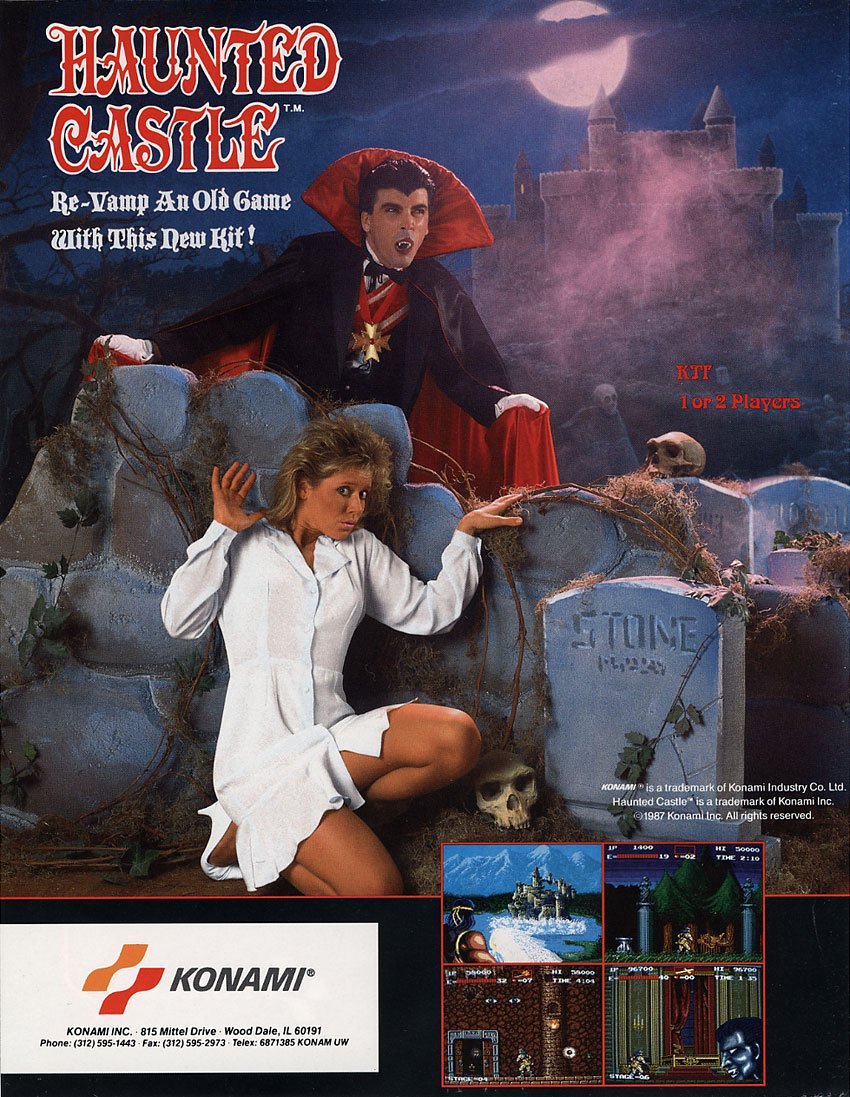

I point all this out because I do love Castlevania’s campy side. The more the series believes its own hype, the more it think it’s a serious medication on the battle between good and evil instead of a fun way to toss a bunch of movie monsters together. I would say that the aesthetic of the American version of the flyer for the arcade game Haunted Castle gives the ‘80s-tastic version of horror that I still come to Castlevania for.

Not to be completely outdone, however, the Japanese flyer takes it more seriously but also establishes a fun video game art trend of “look at this buff guy’s butt.”

I say there’s room in video games for both!